Fifteen years ago we reported on a woman named Jennifer Thompson -- a rape victim who was devastated to learn, years after her assault, that she, and the police, had identified an innocent man who was convicted and sent to prison, while the actual rapist had gone on to attack several more women. Not an uncommon story in this era of DNA exonerations, and Jennifer Thompson has tried for years to do something about it.

Thompson knows firsthand that wrongful convictions scar not just the unjustly convicted, but also the original crime victims, who are often overlooked. So she's doing something no one else has tried, and perhaps only she could pull off -- bringing together crime victims and innocent men, from different cases, for what she calls "healing justice."

Jennifer Thompson: What I'm gonna ask you to do is turn your bowl upside down.

What we saw on day one of a multi-day group retreat Jennifer Thompson is leading sure didn't look like healing… (Raymond smashes bowl) Ten men and women, plus an observer.. (Jennifer: Nice job, Lesley!) smashing bowls with a hammer.

Jennifer Thompson: What I'm gonna ask you to do now is I'm gonna ask you to repair it.

It was quite something to realize that gluing pieces back together at one table were two women who had been raped at the ages of 15 and 12…sitting across from two men who, in unrelated cases, had been wrongfully convicted of sexually assaulting children, and had each spent more than two decades in prison. (Penny: Anyone need a little blob of glue?) At the next table, another woman who survived a sexual assault, sitting beside a man exonerated for rape and murder. And at our table, the partner and daughter of a murder victim.. everyone here part of a case where the wrong man was sent to prison for years and years.

Lesley Stahl: You have said that wrongful convictions aren't a "single bullet," you said they're "bombs."

Jennifer Thompson: A wrongful conviction doesn't hurt like a person. It's not just Raymond Towler got hurt. Like, his whole family got shrapnel. And the victims got shrapnel. And the community received shrapnel because a child molester was still in the community. There's just so many people in a wrongful conviction–

Lesley Stahl: In one case.

Jennifer Thompson: I think it's hundreds of people, for every single wrongful conviction case, that are hurt.

Jennifer Thompson was one of them. She was a college student in 1984, when a man broke into her off-campus apartment and raped her at knifepoint. Jennifer worked with police to create a composite sketch, then identified a man named Ronald Cotton in the photo and physical lineups police showed her. Jennifer testified in court against Ronald Cotton, and was relieved when he received a life sentence.

But after 11 years in prison, DNA testing proved Cotton's innocence and identified the actual rapist, whose photo had not been in the lineup. Ronald Cotton was exonerated.. and Jennifer was wracked with guilt, as she told us in 2009.

Lesley Stahl: Shame?

Jennifer Thompson: Shame, terrible shame. Suffocating, debilitating shame.

Jennifer turned that shame into action. She apologized to Ronald Cotton in person, and then, started speaking around the country to police and prosecutors, sometimes together with Cotton, about how to make wrongful convictions less likely.

But over the years, as exonerations of the innocent have multiplied.. (Exoneree: Finally we're free.) With nearly 3,500 freed so far, based on new evidence including DNA, Jennifer began focusing in on what was being overlooked.

Lesley Stahl: What do you think most people feel and see when they see an innocent man come out of prison?

Jennifer Thompson: It's the day that that man or woman who's wrongfully incarcerated, and their families are rejoicing. (Woman: I know you didn't do it, I know..) It's the day they've been dreaming about, they've prayed for. They're on the court steps, and their arms are raised high, and it's a day of celebration. But for the crime victims, for the murder victim family members, they're sittin' back here sayin', "Hey, hold up a second. This is another nightmare, on top of a nightmare." The victims have been forgotten.

Victims, she says, like Tomeshia Carrington Artis, who was 12 years old when a man broke into her bedroom and raped her.

Tomeshia Carrington Artis: He grabbed me by my throat, and put a knife to my throat, and said if I screamed, he was gonna kill me and my mom.

Penny Beerntsen: Grabbed me from behind, put me in a choke hold--

Penny Beerntsen, sexually assaulted at age 36 as she went for an afternoon run along the shore of Lake Michigan..

Penny Beerntsen: And he said, "Now I'm gonna kill you. Now you're gonna die."

And Loretta Zilinger-White, who was raped at age 15 on the way to school one morning after she'd missed her bus.

Loretta Zilinger-White: It's hard. People expect you to just put it behind you and not think about it again. And they don't realize that it's gonna affect you for the rest of your life.

All these women, like Jennifer, had identified a suspect the police showed them, only to learn years later that those men were innocent, and they were gripped by a whole new nightmare.

Tomeshia Carrington Artis: I felt so bad for h-- for him because I felt like I sent this man to prison. That's all I could think about. I got scared. I felt like-- that he was gonna try to come out and kill me, that-- I mean, I just–

Lesley Stahl: Oh.

Tomeshia Carrington Artis: I shut down.

Lesley Stahl: Did people blame you?

Penny Beerntsen: Oh, absolutely. The first time I went out in public, a friend came up to me and said, "I can't believe you're showing your face."

Tomeshia Carrington Artis: They were saying that I needed to go to prison–

Lesley Stahl: That you needed to go–

Tomeshia Carrington Artis: Yes. That I intentionally sent the wrong man to prison.

Lesley Stahl: Oh, my gosh.

Tomeshia Carrington Artis: Yeah. It was bad.

Memory experts have long understood how crime victims can get it wrong. In our earlier story about Jennifer's case, Professor Gary Wells showed us a simulated crime scene, and then a lineup.

Gary Wells: You know now, after we've talked, probably not to pick anyone.

Lesley Stahl: No, no actually, I-- I actually know who it is, because..

Gary Wells: Yeah, who is it?

Lesley Stahl: I think it's this guy. Am I wrong? Am I wrong?

Gary Wells: Yeah.

Lesley Stahl: I'm wrong?

Gary Wells: Yeah. It's none of them.

Lesley Stahl: [gasps]

Studies have shown again and again, when the actual perpetrator is not in the lineup, witnesses often pick the wrong man, who then comes to replace the original offender in their memory of the crime. In Jennifer's case -- and Tomeshia and Penny's -- the real perpetrators, revealed by DNA years later, had not been in the original lineups.

Jennifer Thompson: 20 years later, when they come to me and say, "By the way"--

Lesley Stahl: Oh. Can't imagine.

Jennifer Thompson: --the person who raped you never went to prison. And the person we thought is innocent. See ya." And, "Oh, by the way, it's all your fault, it's not the system's fault I mean, here was my narrative: "Rape victim falsely accuses an innocent man and sends him to prison." Everything's wrong with that. 'Cause a false accusation denotes a lie.

Lesley Stahl: Deliberate.

Jennifer Thompson: Why would a crime survivor, why would a victim, want the wrong person to go to prison? That doesn't make any sense at all.

Lesley Stahl: You know, when you hear what you're saying, then we get it. But we don't hear it. As you said, there's a blazing headline, "Man is freed: Person who fingered him got it wrong." That's it.

Jennifer Thompson: And the system now doesn't get held accountable for how it failed me, and it failed my family, and it failed the innocent person. And it failed the innocent person's family. And it failed everybody.

That failure, Jennifer told us, is also devastating for families of murder victims, even when they played no role themselves in identifying the wrongfully convicted person. That's what happened to Andrea Harrison and her father, Dwayne Jones. Andrea's mother, Jacqueline, was raped and murdered in 1987, when Andrea was just 3 years old.

Andrea Harrison: It was one of the most horrendous crimes. She was brutally raped, tortured. Someone found her body, walkin' the dog.

A local man named Larry Peterson spent more than 17 years in prison for the crime before DNA testing proved his innocence, and he was released.

Lesley Stahl: Did you know that he was gonna be released? Did they tell you?

Dwayne Jones: No.

Andrea Harrison: No.

Dwayne Jones: No.

Lesley Stahl: For many, many years someone was tried, convicted, and put away.

Dwayne Jones: Yes ma'am.

Lesley Stahl: And then you find out that the DNA doesn't match.

Andrea Harrison: I mean, you go back into fight or flight.

Dwayne Jones: Yeah.

Lesley Stahl: You got scared?

Andrea Harrison: Absolutely–

Dwayne Jones: Absolutely we did.

Lesley Stahl: Can you tell us of what?

Andrea Harrison: Who's the person? Who's-- who's-- who hurt my mother? What happened to Jackie? Who did it? Whoever that person is, they're still out there–

Dwayne Jones: They're still there.

But since Larry Peterson's exoneration, with the case now cold, they feel the original crime -- and victim -- have become an afterthought.

Andrea Harrison: It's always been, "What do you think about Mr. Peterson?" That is not my charge. I care about Jackie. I'm worried about Jackie. What about Jackie?

But even while victims and their families are left reeling in the wake of wrongful convictions, Jennifer knows from her friendship with Ronald Cotton, and her work with other exonerees, that heady, blissful first day of freedom is just the start of a tough, years-long struggle to rebuild.

Raymond Towler, exonerated after 29 years in prison.. 29 years.. plays in a band with other exonerees, and says he struggles with the lingering stigma, and hurt, of being charged with such a heinous crime.

Lesley Stahl: Tell us, if it's not too painful, what the crime was–

Raymond Towler: It's painful. (laugh)

Lesley Stahl: I know. I'm–

Raymond Towler: I'm laughin'--

Lesley Stahl: --sorry–

Raymond Towler: --over it, but it's-- it is painful. But it-- it was rape of 11 and 12-year-old kids.

When DNA testing finally proved Towler's innocence and won his freedom, he says it was thrilling.. but also daunting.

Lesley Stahl: The adjustment was difficult?

Raymond Towler: Yeah. I couldn't even really go out the door by myself.

Chris Ochoa: You don't feel like you fit in anywhere. I-- at least I didn't.

Exonerees' stories are often filled with egregious police and prosecutorial misconduct -- in Chris Ochoa's case, abusive interrogations that led to a false confession to rape and murder; for Howard Dudley, evidence withheld by prosecutors that likely would have cleared him of child sexual abuse, for which he served more than 23 years.

Howard Dudley: I always dreamed of bein' there with my kids. See the football game, see 'em on the basketball court. Didn't get a chance to see none of that.

Jennifer Thompson: So I would like for everybody to introduce themselves..

So Jennifer came up with a novel idea.

Jennifer Thompson: So I am Jennifer Thompson, I am a victim-survivor.

Raymond Towler: My name is Raymond, Raymond Towler, I'm an exoneree.

Loretta Zilinger-White: My name is Loretta..

She started an organization called Healing Justice that brings together exonerees..

Chris Ochoa: My name is Chris.

Howard Dudley: I'm an exoneree.

And crime victims…

Penny Beerntsen: My name is Penny..

All from different cases…

Tomeshia Carrington Artis: I am Tomeshia..

As well as family members…

Lisa Pawlowski: My brother was an exoneree.

Andrea Harrison: My name is Andrea..

Healing Justice paid to bring them from around the country to this rented retreat center in Virginia, where they will spend three days sharing stories.. playing games.. and eating all their meals together. This is the 17th retreat Healing Justice has done.

Lesley Stahl: How effective is it when it's not the same crime?

Jennifer Thompson: Very effective. There's something powerful and healing when an exoneree can hear what the victim in their case must have felt like. And for crime survivors, it's really healing to also hear about the experiences of exonerees.

Chris Ochoa: The biggest thing I lost was trust.

Jennifer Thompson's goal when she created the nonprofit organization Healing Justice in 2015, was to help all groups harmed by wrongful convictions. Healing Justice now advises prosecutors' offices around the country on dealing more effectively and empathetically with crime victims in exoneration cases, and they've recently gotten a grant from the Justice Department to expand those efforts. But it's what they call the "healing" side of their work that is most meaningful to Jennifer.

She did coursework in trauma recovery, and worked with psychologists to design a program to safely bring together victims of crime, and exonerees. They work in small groups on the wounds left behind when the justice system gets it wrong.

Remember the breaking and gluing back together of those bowls?

Jennifer Thompson: Did anybody notice how fast and easy it was to break it, and how hard it is to put it back together again?

That was just the start of this retreat's opening exercise.. and perhaps a metaphor for the whole endeavor.

Jennifer Thompson: What I'm gonna ask you to do now, is to paint your broken places with gold. This is actually 24 karat gold paint.

She told us it's called kintsugi.

Lesley Stahl: Kintsugi.

Jennifer Thompson: Kintsugi. Mm-hm.

Lesley Stahl: What is that?

Jennifer Thompson: It's the Japanese concept that even in our broken places, we're still beautiful. Because we're strong at our broken places. And we're not disposable.

But before they can paint their real wounds with gold, they have to look hard at the breaks that need repair.

Andrea Harrison: I lost part of my heart.

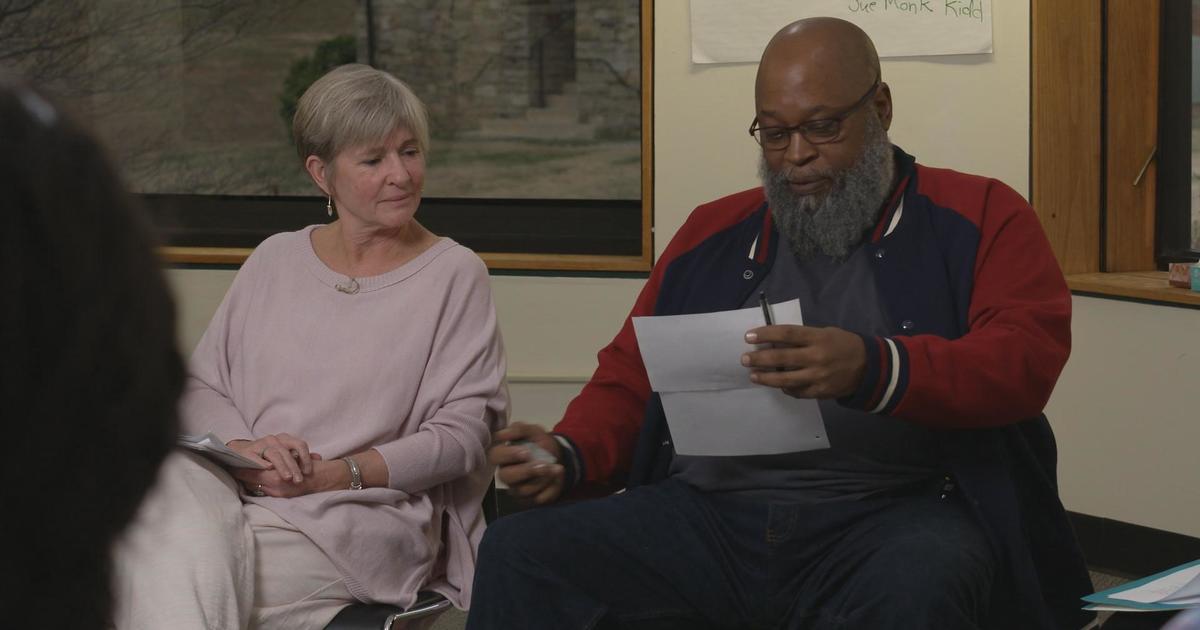

So, sitting in a circle, using a rock to give whoever holds it the floor, and with a Healing Justice social worker always present, they talked about their losses.

Loretta Zilinger-White: I lost believing in myself. I had so much confidence. I had so much. [teary, shakes head]

Raymond Towler: That first, you know, slam of the doors. Everything got real right then, you know? I seen people suicide-- death by cop: just gettin' beat up, killed. [voice breaks] You know it all comes back. And I have to keep remindin' myself, you know, f-- right here, I'm in the present, right now.

Penny Beerntsen: The hardest part for me is hearing what the exonerees went through in prison. It's so hard to hear, but it's so necessary.

Jennifer Thompson: So what I want to do today is..

On day two of the retreat, Jennifer led an exercise on how the harsh words used against each of them end up becoming internalized.

Jennifer Thompson: You might have been called a liar. You might have been called a rapist. And those words really do take on a life of their own. I'd like for you to write a letter to yourself, from the space of the critical mind, that loop that plays in your head over and over again,

Lesley Stahl: You had them write letters. What was the purpose?

Jennifer Thompson: I've done this before. When they're writing it, they're not happy. And then I had them read it out loud to the circle. They didn't like it.

Chris Ochoa: "Dear Chris, You've failed in life. Why did you confess? I would never have confessed."

Andrea Harrison: Why can't you just be quiet?

Raymond Towler: "Dear Raymond, you are a angry Black man. You will never know love. You will always be a prisoner." [Jennifer sighs]

And then there was Loretta's

Loretta Zilinger-White: "Dear Loretta, you deserved to be raped and beaten. You really don't deserve to be alive. [Breathe in] You aren't brave nor strong. You are a failure as a woman and a mother.."

Loretta, Jennifer told us, faces one of the most excruciating situations for a victim in an exoneration case.. when the DNA clears one man but doesn't identify who the actual assailant was.

Loretta Zilinger-White: I'm stuck.

She told us she relives the assault daily, and can't get the exonerated man's face out of her memory.

Lesley Stahl: So even though he was cleared through DNA, his face is still there.

Loretta Zilinger-White: Yes. The DNA said it wasn't him. [long silence, tears]

Lesley Stahl: You didn't believe it.

Loretta Zilinger-White: No. I feel guilty. 'Cause I feel like I did something wrong.

Lesley Stahl: So you're having both the feeling that he was the one, and that you did something wrong.

Loretta Zilinger-White: Yes.

Lesley Stahl: Oh, my God, you really are stuck.

Loretta Zilinger-White: I don't know who did this.

For Andrea Harrison, whose mother's killer also remains unknown, it's a familiar struggle.

Andrea Harrison: What was told to me was that he was the person who murdered my mother, and so that was a belief of mine for a lotta years. I can't get that outta my head.

Lesley Stahl: On his side of it, I mean, that's sad.

Andrea Harrison: It is sad.

Dwayne Jones: It is sad.

Andrea Harrison: The justice system failed him just like it did us.

Until now, Andrea and her father had not been willing to attend a retreat with exonerees present.

Lesley Stahl: Do you think that the exonerated person, and the victim are almost pitted against each other, when they shouldn't be? They're both victims of the same perpetrator, who knows someone's sitting in–

Jennifer Thompson: That's right.

Lesley Stahl: --jail for what he or she did.

Jennifer Thompson: That's right. At the end of the day, when an innocent person's in prison, a guilty person's not. We should all be concerned about that.

Lesley Stahl: And maybe they go off and do it many more times.

Jennifer Thompson: In my case, the person who wasn't caught committed six more first-degree rapes before he was ever apprehended.

Raymond Towler: I just love that we're here, working on this.

In the circle, after reading the critical letters, Jennifer turned the tables.

Jennifer Thompson: So I want you to write a second letter now to yourself from the self-compassion voice, the voice that you would use for the person you love the most.

Jennifer Thompson: So they rewrote it.

Lesley Stahl: They did. They turned it?

Jennifer Thompson: And they-- oh, yeah. And then they read that out loud. And their faces-- they smiled when they read it.

Raymond Towler: Dear Raymond, You have a kind heart. You are loved. Raymond, your dreams have come true and you are free to dream more and create.

Tomeshia Carrington Artis: You are a great mother, grandmother, wife, daughter, sister, friend, and so on and on. Keep going. You got this.

Dwayne Jones: I've seen you stumble and I've seen you bounce right back. [Andrea nods]

Loretta Zilinger-White: Dear Loretta, You know that it's never too late to follow your dreams. You should never stop believing in yourself. You didn't deserve to be hurt by anyone or anything. I will always be your biggest fan and supporter. I love you.

Jennifer Thompson: Well, that was different. So why is it that we speak to ourselves in a way that we would never speak to the people that we love?

Raymond Towler: Something that I need to change, you know, is that it was actually harder to write the happy letter for me. I do believe the good things about myself. But I don't think I really say 'em to myself enough.

Jennifer Thompson: And the reality is if we really want to-- to do good in the world, hating ourselves serves nobody at all.

After two emotion-filled days came a scene we weren't expecting.. the group gathered together for improv games.. acting like animals, smiling, and laughing.

Lesley Stahl: You play a lotta games.

Jennifer Thompson: Well, the games are just really a way of inviting that child to come back and play again. If you feel safe, you can pretend like you're a monkey. (laughter) You can do all kinds of ridiculous things, and it's okay, because everybody else is doing it too.

We noticed a loosening.. and connecting. Later that night over an art project, the kind of impromptu conversation Jennifer says this retreat is all about.

Raymond Towler: How can somebody look at me and think that I would do somethin' so heinous like that? That's part of the trauma, for me.

Loretta Zilinger-White: When you hear some of our stories, do you ever, like blame us?

Raymond Towler: Like, me-- bein' a exoneree?

Loretta Zilinger-White: Yeah. Do you ever see yourself blaming the victims?

Raymond Towler: You didn't do anything wrong. It's not your fault.

The next morning, as they gathered in the circle for the third and final day..

Penny Beerntsen: I feel blessed.

Chris Ochoa: I feel light as a feather.

The mood had shifted.. dramatically.

Andrea Harrison: I feel-- open [smiles]

Loretta Zilinger-White: I feel courageous.

Raymond Towler: I feel-- nurtured. Even though it's painful to let it out, I think you guys do it because you know it's gonna help the next person. And it has.

Lesley Stahl: So how did the retreat go?

Dwayne Jones: Very enlightening. Very powerful.

Loretta Zilinger-White: We took off the mask that everybody sees.

Lesley Stahl: What questions did you ask each other, exonerees to crime victims and back around?

Andrea Harrison: I asked, "What happened to you?"

Tomeshia Carrington Artis: And everyone was honest.

Dwayne Jones: And everybody was honest. I asked-- right away, I shook Mr. Howard's hand, and I feel for this man and my other two friends back there that are exonerees. I see it now, 'cause we only looked from our side of the table. We never seen it from their side.

Raymond Towler: I had that fear, even when I came here, I didn't know if I would be comin' into hate because I was exoneree. 'Cause, you know, nobody believed me for, you know, 30 years.

Tomeshia Carrington Artis: I th-- I think we believe it. I th–

Raymond Towler: Thank you. (laughter)

Loretta Zilinger-White: We do.

Loretta Zilinger-White: I had questions myself for an exoneree. And I was able to build up the courage to even ask Raymond, because I still hold this guilt. And I was finally able to let it go after talkin' to him. I knew he was speakin' from his heart. And it took 30 years for him to (voice breaks) let me get that guilt off of me.

Andrea Harrison: Hmm.

Lesley Stahl: Wow.

Loretta Zilinger-White: (voice breaks) I thank you. [takes Raymond's hand]

Lesley Stahl: Do you have any guilt?

Jennifer Thompson: For what happened to Ronald?

Lesley Stahl: Uh-huh.

Jennifer Thompson: No. Not anymore. I feel so sad that for 11 years he was in prison for something he didn't do, but I'm also really sad that I got raped at knifepoint and chased around, you know, a neighborhood in the dark while I didn't have any clothes on. I feel deep amount of sadness for these cases, and for everybody who's impacted by them.

Loretta to Howard: May you keep spreading your love to everyone that needs it.

So as the retreat drew to a close, they clasped hands and shared wishes for one another.

Lisa to Penny: Penny, may you continue on your journey of healing.

Lesley Stahl: What happened in your case that allowed you to heal?

Jennifer Thompson: (laugh) I think I'll always be healing. But I think what has helped me, more than anything, is the relationships I've built along the way, with people that-- that have been harmed and hurt just like me.

Lesley Stahl: 'Cause you're helping other people.

Raymond to Jennifer: Jennifer, may you always be in our lives, and may you always be courageous.

Jennifer Thompson: I'm helping other people, but (laugh) what they don't realize is they're also helping me.

[They all spin out of hands clasped]

Raymond: I didn't know that move. [laugh]

Lesley Stahl: They're healing.

Jennifer Thompson: They are healing. And I wanna walk with them on that journey.

Jennifer with others after spin: Whoo-ee!

Produced by Shari Finkelstein. Associate producer, Collette Richards. Broadcast associate, Wren Woodson. Edited by Daniel J. Glucksman.