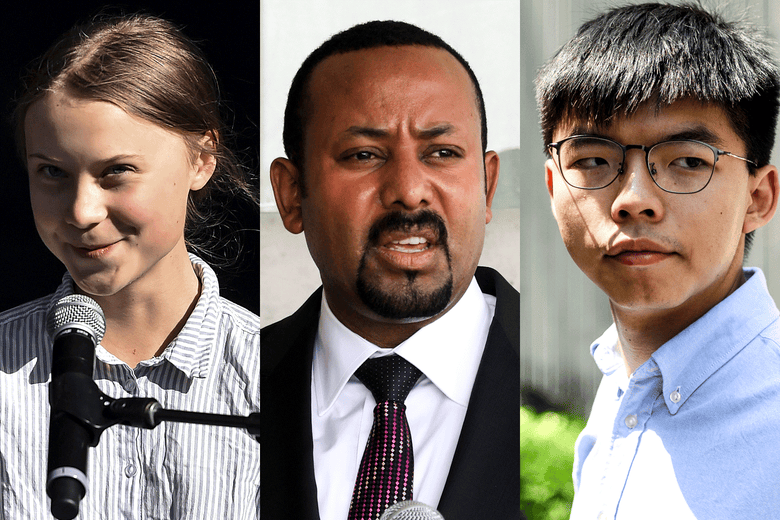

Greta Thunberg, Abiy Ahmed, Joshua Wong

Photos by Minas Panagiotakis/Getty Images, Gali Tibbon/AFP/Getty Images, and Philip Fong/AFP/Getty Images.

The Nobel Peace Prize, this year’s recipient of which will be announced on Friday, is extremely difficult to predict for many reasons. First, there’s the number of nominations—there are reportedly 301 this year, ranging from Donald Trump, to Edward Snowden, to Jose Andres, mainly submitted by members of parliaments from around the world. There’s also the secrecy surrounding the prize: The full list of nominees won’t be released for 50 years, even if many have already been made public by the nominators. Mostly, though, this is a tough race to call because it’s not particularly clear what the prize is actually for.

In its early years, the prize was most often given to diplomats and political leaders for concrete acts of diplomacy. In recent years, it’s just as often been given to individuals and organizations involved in activism or awareness-raising about some worthy issue. Also, the definition of “peace” has been expanded over decades to include democracy, human rights, gender and racial equality, environmental justice, and a host of other concerns. This is not to say the winners are necessarily underserving—last year, the prize was awarded jointly to the Congolese doctor Denis Mukwege and the Iraqi Yazidi activist Nadia Murad for their work combating sexual violence in war—but the award is less a measure of who did the most to advance the cause of peace in any given year than what person or organization a group of Norwegian politicians think is worthy of celebration in any given year via an award named after a Swedish arms dealer.

Just because it’s nearly impossible to predict, though, doesn’t stop people from trying. Here’s a look at some of the people and organizations getting the most buzz this year.

Greta Thunberg

The Swedish climate activist has been getting most of the coverage ahead of this year’s award, and she’s been receiving the best odds on betting sites. It’s not hard to see why. The weekly school strike she began last year has grown into a global movement, and it’s made the righteous and blunt-spoken Thunberg the face of international climate-change activism.

At 16, she would be the youngest person ever to win the award—Malala Yousafzai won it at age 17 in 2014. It would also be the second prize given in relation to work revolving around climate change: Al Gore and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change were jointly awarded in 2007.

Still, some Nobel watchers are skeptical about her chances. Thunberg became much more of a global public profile this fall, with her highly publicized sail across the Atlantic and blistering address at the U.N. General Assembly, well after the Nobel Committee supposedly formed its shortlist of candidates back in February. (The timing issue also works against another much-discussed candidate—New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern—as her widely lauded response to the Christchurch mosque attack happened in March.)

Still, Thunberg was already well-known in Scandinavia—she was nominated by a group of Norwegian MPs—and this would be a timely and popular choice. (Maybe not so popular with one of her fellow nominees.) If the movement she sparked continues to grow, it seems likely she’ll win at some point, if not this year.

Hong Kong activists

Henrik Urdal, director of Peace Research Institute Oslo, who writes a widely cited Peace Prize shortlist every year, is one of those who is doubtful about Thunberg’s chances. He does, though, think it’s likely the prize could recognize the “contributions of young people.” Aside from the climate movement, the most globally visible youth-led movement of 2019 has been Hong Kong’s pro-democracy protests.

While this year’s protest movements are notable for being leaderless, there are some well-known youth activists associated with it. Joshua Wong and Agnes Chow, just to name two, became the public faces of the 2014 Umbrella Movements protests when they were still teenagers and went on to found the pro-democracy NGO Demosisto. The group’s co-founder, Nathan Law, was elected as the youngest Hong Kong legislator ever in 2016, though he was later disqualified. These activists have been on the committee’s radar for a while—they were also nominated in 2018 by a group of U.S. lawmakers—but this year’s events have only made their work more urgent.

Other opponents of Beijing have received the prize, including the Dalai Lama in 1989 and the late activist Liu Xiaobo in 2010. (The imprisoned Uighur academic Ilham Tohti is also nominated this year.) As with those prizes, the reaction from Beijing to an award for Hong Kong activists would be furious. China has been swift to push back against support for Hong Kong expressed by even the most minor public figures. China and Norway only recently resumed trade talks that had been frozen as a result of Liu’s award. Does Norway have the stomach for another showdown with a superpower?

Reporters Without Borders/Committee to Protect Journalists

Urdal also notes that there’s never been a peace prize dedicated to press freedom, and it would certainly be timely in 2019. The number of journalists killed around the world has been steadily increasing, with violence perpetrated by criminals, terrorists, and often—as in the case of the Washington Post’s Jamal Khashoggi—national governments. Leaders like U.S. President Donald Trump, Hungary’s Viktor Orban, and Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro aren’t exactly helping matters by demonizing the press as national enemies.

There are any number of publications and individual reporters who could be honored, but awarding one of these venerable global press freedom organizations could be a way to more broadly highlight the issue.

Abiy Ahmed

The prime minister of Ethiopia is another popular choice for the 2019 prize. After taking over a stagnating authoritarian country last year, following mass protests, the 43-year-old Abiy has instituted a series of bold and transformative reforms. Those have included lifting a years-old state of emergency, releasing thousands of political prisoners, unblocking hundreds of media outlets, lifting bans on opposition parties, and prosecuting human rights abusers. Most surprisingly, he reached a peace deal to end the border dispute with neighboring Eritrea in June—one of world’s longest-running armed conflicts. In an era when democracy and human rights seem to be declining, Africa’s second-largest country has been a rare bright spot.

But there are still a lot of uncertainties in Ethiopia, mainly the country’s massive internal displacement crisis—driven by ethnic violence—that threaten to delay next year’s planned parliamentary election. Abiy has defied expectations so far, but it may be a little too soon to award him just yet.

International Criminal Court/Coalition for the International Criminal Court

Whatever he may think, Trump is not going to win a Nobel Peace Prize for his negotiations with Kim Jong-un or for anything else. It’s more likely that the Nobel committee will give an award specifically to needle him. One candidate for that could be either the ICC or the organization that advocated for its creation and continues to support its work, which has been nominated several times.

The court, which the U.S. never joined, has never been particularly popular here. But the Trump administration, particularly under former national security adviser John Bolton, has gone out of its way to target the ICC, including a move in March to slap visa bans on its officials over an ongoing investigation of alleged war crimes in Afghanistan.

Even aside from Trump, it’s been a rough couple of years for the Hague-based court. A number of members have dropped out rather than participate in its investigations; it’s been unable, for procedural reasons, to target crimes conducted in the world’s bloodiest ongoing conflict, the war in Syria; and a number of African governments have attacked it—self-servingly, but not entirely without cause—for being a neo-imperialist institution that disproportionately targets African perpetrators.

Still, an award for the court and its supporters could be a show of solidarity for the very concepts of international law, justice, and accountability, at a time when they are under withering attack.