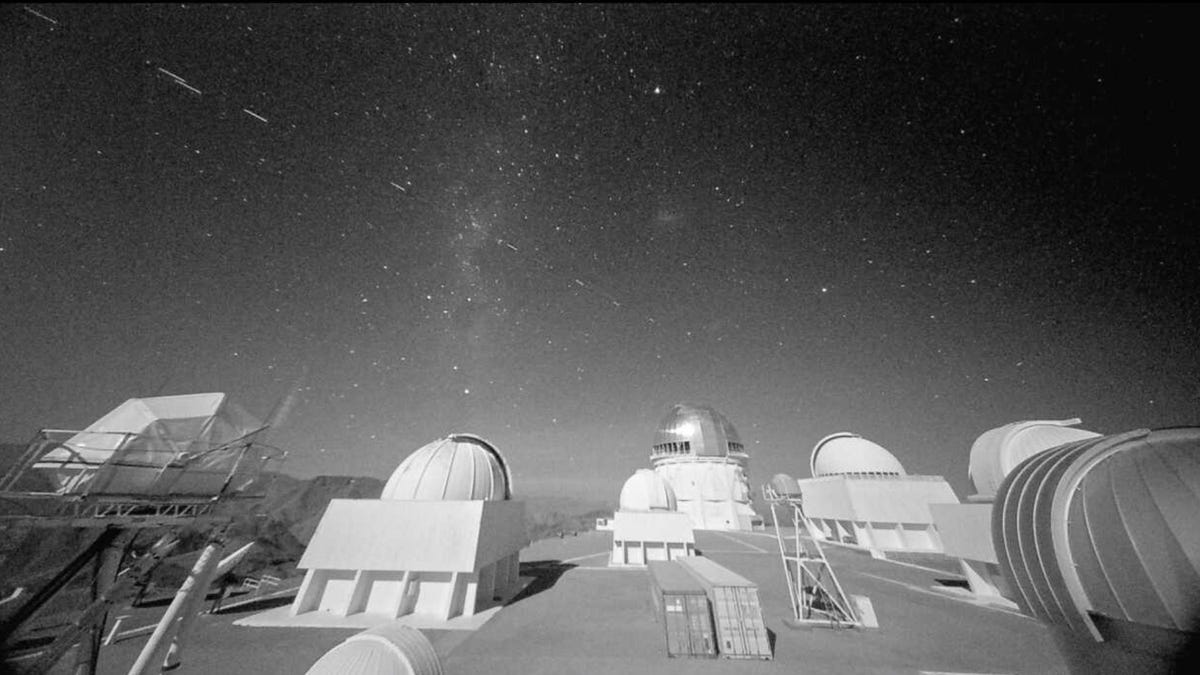

Astronomers at a Chilean observatory were rudely interrupted earlier this week when a SpaceX satellite train consisting of 60 Starlink satellites drifted overhead, in what scientists are apparently going to have to accept as the new normal.

Launched into orbit on November 11, the Starlink smallsat train took five minutes to pass over the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile, according to a tweet from astronomer Clarae Martínez-Vázquez.

“Wow!! I am in shock!!,” tweeted Martínez-Vázquez. “The huge amount of Starlink satellites crossed our skies tonight at [Cerro Tololo]. Our DECam [Dark Energy Camera] exposure was heavily affected by 19 of them!,” to which she added: “Rather depressing... This is not cool!”

Responding to this tweet, astronomer Cliff Johnson, a team member and a CIERA Postdoc Fellow in Astronomy at Northwestern, tweeted out a view of the disrupted data, showing an array of satellite trails strewn across an image of space.

The astronomers were collecting data using the DECam instrument, a high-performance, wide-field imager on the CTIO Blanco 4-meter telescope, as part of the DELVE survey, which is currently mapping the outer fringes of the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds as well as a significant fraction of the southern sky at optical wavelengths. Key goals of the project are to study the stellar halo around the Magellanic Clouds and detect new dwarf galaxies in orbit around the Clouds or the nearby Milky Way.

But this research was punctuated as the Starlink train passed overhead during the early morning of Monday, November 18.

“In this case, 1 out of about 40 exposures we took during our half-night of observations was affected by the satellite trails,” Johnson told Gizmodo in an email. “And in the case of that single exposure, a maximum of 15 percent of the image was affected by the trails. Beyond the image itself, we also had to be careful as the trail-affected image also impacted our survey operations due to the large number of image artifacts biasing our quality-control measurements.”

Taken as a whole, however, “these numbers tend to show that the effect on our science was more on the annoyance level rather than total disruption,” he wrote. That said, “this may only be the beginning of problems for astronomers, so I believe the community reaction and alarm is warranted.” Should the proposed sizes of these satellite megaconstellations—which are projected to include upwards of tens of thousands of individual elements—actually be achieved, “that has the potential to significantly impact our observational data,” said Johnson.

A similar thing happened earlier this year after the first batch of 60 Starlink satellites was delivered to orbit, with some people even believing they were UFOs. Alarmed by the inaugural batch of Starlink satellites, the U.S. American Astronomical Society issued a warning, saying megaconstellations could threaten scientific observations of space.

The train effect, in which the satellites are lined up neatly in a bright row, is a temporary one. Eventually, the smallsats disperse and enter into their own unique orbits in a process that takes a few weeks. That said, the number of objects in space—dispersed or not—is about to experience a dramatic uptick.

As it stands, the impacts of these satellite trains “remain manageable” and the “worst effects temporary,” Johnson told Gizmodo.

“I agree with the tone of the recent IAU statement that calls for immediate, meaningful discussion between regulators, satellite providers, and astronomers to highlight ways that impacts to astronomy can be minimized—and not just optical, but radio astronomy as well—and rule out the worst-case scenarios of unlimited launches and unchecked deployments,” Johnson told Gizmodo.

In response to these concerns, SpaceX has said it is taking steps to color the base of Starlink satellites black, in order to minimize their brightness. Experts aren’t convinced that’ll work, as some observatories use super-sensitive instruments to detect even the faintest objects.

Scientists will likely have to get used to these sorts of disruptions, as regulating bodies aren’t lending a sympathetic ear. SpaceX has already received approval from the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to launch 12,000 Starlink smallsats, and in October, the Elon Musk-led private space firm asked the FCC for permission to launch an additional 30,000 satellites on top of that by the mid 2020s. These satellite trains, along with their associated megaconstellations, will soon become a regular fixture of the night sky—and that doesn’t include constellations that are set to be built by SpaceX’s competitors, including networks proposed by OneWeb, Telsat, and Amazon.

With the starry night already obscured by light pollution from our cities, it seems an unhindered view into space may soon elude astronomers as well.