3D printing homes on Earth, someday the moon

This is an updated version of a story first published on Oct. 8, 2023. The original video can be viewed here.

There was a time when futurists were predicting that the advent of 3D printing was going to change our lives.. that each of our houses would have a 3D printer to make whatever items we need. What virtually no one predicted, though, was that there might soon be 3D printers that could construct almost the entire house.

But, as we first reported last fall, that's just what a 7-year-old Austin, Texas company called Icon is doing.. 3D printing buildings. And if you believe Icon's mission-driven young founder, 3D printing could revolutionize how we build, help create affordable housing, and even allow us, to.. wait for it.. colonize the moon. Sound out of this world? Take a look..

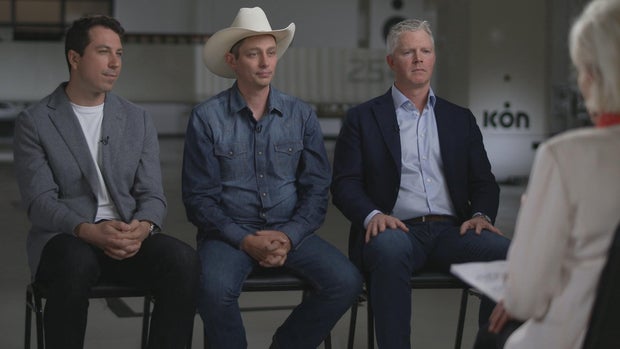

What you're watching is the building.. actually, the printing, of a 4-bedroom home. On this construction site, there's no hammering or sawing, just a nozzle squirting out concrete -- kind of like an oversized soft serve ice cream dispenser -- laying down the walls of a house one layer at a time. It's the brainchild of a 41-year-old Texan who's rarely without his cowboy hat, Jason Ballard.

Lesley Stahl: 3D printing a house.

Jason Ballard: Yes, ma'am.

Lesley Stahl: People are gonna hear that and say, "No."

Jason Ballard: We're sitting inside one right now.

Lesley Stahl: This house was printed?

Jason Ballard: Yes, ma'am.

Lesley Stahl: Oh.

Jason Ballard: There you are.

Lesley Stahl: Look at this.

Jason Ballard: Welcome.

And so was this one. Does a concrete home printed by a robot have to look cold and industrial? Maybe not.

Lesley Stahl: I like the curved wall.

Ballard gave us a peek at the first completed model home in what will soon be the world's first large community of 3D-printed houses – a hundred of them.. part of a huge new development north of Austin. They'll start in the high $400 thousand range. How exactly does 3D printing a house work? Well, it starts with this one-and-a-half-ton sack of dry concrete powder, which gets mixed with water, sand, and additives, and is then pumped to the robotic printer.

Conner Jenkins: Now, you are looking at how we control the bead size.

Conner Jenkins, Icon's manager of construction here, explained that the printer completes one layer called a "bead" every 30 minutes, by which time it's hardened enough to be ready for the next bead. Steel is added every 10th layer for strength.

Lesley Stahl: The amount of change you're making is–

Conner Jenkins: Tiny.

It takes about two weeks to print the full 160-bead house. Jenkins gave me the controls.. an iPad.

Conner Jenkins: So look, Lesley, that's a little skinny. Will you press the plus 1% real quick?

Lesley Stahl: Aren't you worried?

Conner Jenkins: Done. You just increased the bead size incrementally.

Lesley Stahl: I'd be worried if I were you.

But turns out the path is entirely pre-programmed. I couldn't mess it up if i tried.

Lesley Stahl: Don't tell the people–

Conner Jenkins: I think that's the most gorgeous bead I've ever seen. I think this'll be the highest selling house. (laughs)

For now, as Jason Ballard showed us, Icon is only 3D printing walls, with cutouts for plumbing and electricity. Roofs, windows and insulation are added the old-fashioned way, by construction workers. He calls it a paradigm shift in how we construct our housing.

Lesley Stahl: But why do we need a big shift like that?

Jason Ballard: 'Cause right now, it is too expensive, it falls over in a hurricane, it burns up in a fire, it gets eaten by termites. The way you try to make it affordable is you trim quality on materials. You trim quality on labor. The result is these cookie cutter developments. And, like, this is not the wor-- like, we are not succeeding at something we have to get right. And on top of that, it's an ecological disaster. And I would certainly say, it is existentially urgent that we shelter ourselves without ruining the planet we have to live on.

Jason Ballard: Fire resistant, flood resistant..

Ballard showed us a sample of a 3D-printed wall beside a conventionally built one.

Lesley Stahl: You say it's faster, more efficient.

Jason Ballard: Yes.

Lesley Stahl: Why do you say that?

Jason Ballard: What you've got, let's count the materials. Siding, one. Moisture barrier, two. Sheathing, three. Stud, four. Drywall, five. And then float tape and texture, you can count that either as one or three, but you've got at least half a dozen novel steps that have to take place to deliver an American stick frame wall system. By comparison, we need a single material supply chain, delivered by a robot.

Lesley Stahl: Let's talk about waste.

Jason Ballard: Yes, ma'am.

Lesley Stahl: Over here.

Jason Ballard: At the end of constructing a home with these materials, there are truckloads, and truckloads of waste left over. These studs are gonna have off-cuts that go into a waste pile. Same with siding, same with drywall.

Whereas with 3D printing, he says, you only print what you need.

Jason Ballard: So in short, like if an alien came down to Planet Earth and saw these two ways of building and said, "From first principles, which is better?" The alien would go, "Stronger, faster, termite resistant, fire resistant, like by a mile this is the best way to build.

Though old-school construction workers may disagree. If Ballard sounds a little like a revved-up salesman, or a preacher, there's a reason for that. He grew up in east Texas, a studious, outdoorsy, spiritual kid, first in his family to graduate from college.

Lesley Stahl: You were thinking about becoming an Episcopal priest.

Jason Ballard: Yeah, I was almost an Episcopal priest. But along the way, I started just, like, getting this, like, itch about housing not being right. So I studied conservation biology. I got involved in sustainable building, and I worked at the local homeless shelter. And so now I'm thinking about homelessness and I'm working in sustainable building. Along the way, my hometown gets destroyed by a hurricane. And I have to go help my family pull drywall outta their house. I-- I feel like–

Lesley Stahl: Oh, wow.

Jason Ballard: --life is just putting housing in front of me, right as I've been, like, approved to go to seminary. And so I go to my bishop, the Bishop of Texas, Andy Doyle. He's still the Bishop of Texas. And-- I said, "What do I do?" (laughs) And at the end, he said, "Jason, I want you to pursue this housing thing like this is your priesthood. This is your vocation. And if it doesn't work out, the church has been here for a long time. We'll still be here."

Lesley Stahl: But that must've turned the switch for you.

Jason Ballard: It did. It made it more than a hobby or a business, right, that it sorta became a mission.

He began pursuing that mission with Evan Loomis, a buddy from Texas A&M who had gone into finance.

Evan Loomis: As we looked at it, like, nobody had incorporated kinda the holy trinity of innovation to housing which was robotics, advanced materials, and software.

So in a borrowed warehouse on nights and weekends, and having read everything they could find about the mechanics of 3D printing, they tried to design a 3D printer that could make a building.

Lesley Stahl: How big was it?

Jason Ballard: It was ten feet, by 10 feet, by 10 feet. So it would've-- it would've printed-- if we had ever gotten it to work, which we did not-- (laughs) it would have printed, like, a 100 square foot, like, demonstration building.

They didn't get it to work, but enter Alex Le Roux, a recent Baylor engineering graduate, who was tinkering with a similar idea.

Lesley Stahl: Did you ever actually build anything?

Alex Le Roux: Yeah I did.

Lesley Stahl: What was it?

Alex Le Roux: A printed shed. A shed doesn't sound too cool, but it was a big milestone.

Jason Ballard: It's a real structure.

Alex Le Roux: Yeah.

The three co-founded Icon in 2017, and soon got funding to print a small house to unveil at Austin's SXSW festival the following spring. They built a new, larger printer, that worked.

Alex Le Roux: And we got really excited.

But the kinks hadn't quite been worked out.

Alex Le Roux: So at one point, we ran the printer into the print.

Lesley Stahl: Explain that.

Jason Ballard: It was supposed to go up, and it went down, and then drove into the house (laughs) and, like, pushed a buncha–

Alex Le Roux: Exactly.

Jason Ballard: --layers off.

Funny now, but not so much at the time.

Jason Ballard: Some engineers folks who were, like, helping us, sat us down and said, "Guys, it's been a great effort. But you're not gonna get there. So, like, why don't you guys get some rest?" And we were basically like, "Get out of here." (laughter) We're like–

Evan Loomis: It's true.

Jason Ballard: --"A--anyone who wants to sh-- to finish this home may stay; everyone else needs to leave."

Lesley Stahl: And the three of you all agreed on that?

Alex Le Roux: Yeah.

Jason Ballard: We knew that we were on to something. And, like, we-- this was, like, our shot. And we weren't gonna miss it.

They worked round the clock, and made the festival deadline by just hours.

Evan Loomis: Hey Ballard, any words for the victory lap?

Jason Ballard: Never, never never never give up.

Jason Ballard: I stand by those words. Yeah, sure. (laughs) Never give up.

He showed us the 350-square-foot finished house.

Lesley Stahl: It's a small little house, but it's kind of elegant.

Jason Ballard: "Well, I'll be. That's not so bad." I mean I think (laughs) that's kinda how people felt about it–

Lesley Stahl: Yeah.

Jason Ballard: It was, like, better than they expected. And it was easy to believe, "Well, they'll get better."

That small little house won Icon a lot of attention.. an innovation award.. investors.. meetings with the military.. and with another Austin innovator -- Alan Graham, who created a village called Community First! that provides small homes to several hundred of the formerly homeless.

Alan Graham: Our goal was really the most despised, outcast, lost and forgotten of our community.

Lesley Stahl: Oh, wow.

Alan Graham: Average time on the streets is nine years. Average age of death is 59.

Jason Ballard: It's an absolute miracle out there. And so when we were ready to start building homes, one of the first organizations we reached out to was Alan Graham.

So Icon 3D printed a welcome center, and then six small houses for village residents. That's how 73-year-old Tim Shea, who battled heroin addiction for decades, in 2020 became the first person in this country to live in a 3D-printed home.

Lesley Stahl: Before I saw these houses in my mind, I thought it must be cold. You're shaking 'cause you don't think that.

Tim Shea: No. Just the opposite. You feel embraced-- you know, enveloped.

Alan Graham: People that live, that are in the economic strata, the men and women that we serve are gonna be the last people on the planet that are gonna benefit out of new technology. And he wanted to make sure that they were the first.

Lesley Stahl: The first person in North America to live in a 3D-printed house was homeless.

Tim Shea: Yeah, I-- isn't that somethin'?

The years since have seen tremendous growth for Icon: a new factory to build more printers, and improve the quality of its concrete and a facility called 'Printland' to experiment with new designs. Icon has printed small homes in rural Mexico, vehicle hide structures for the Marine Corps, huge barracks for the Army and Air Force and a deluxe showcase home featuring wavy walls and curves that would be prohibitively expensive if built traditionally, but not when programmed into a 3D printer.

Lesley Stahl: So in your minds, is your customer a homeless person? Or is your customer me?

Jason Ballard: There's a trick here because what our heart wants to do is to serve the very poor. And it's often been, like, confusing for people to understand. It's like, "I thought you guys were helping homelessness. Why are you building that fancy house?"

Lesley Stahl: Yeah.

Jason Ballard: I would resign if I was only allowed to build luxury homes. And we would go bankrupt right now if all we built was 3% margin homes for homeless people. But once this technology arrives in its full force-- I think it fundamentally transforms the way we build.

It has been a staple of science fiction forever — humans living and working on the moon. But for NASA, that dream is almost within reach. Their new Artemis program plans to return American astronauts to the moon for the first time in more than 50 years — this time, not just to visit, but eventually to stay and even use the moon as a base for exploring Mars and beyond. But staying on the moon requires infrastructure — landing pads, roads, housing — and you can't exactly bring two-by-fours and sheetrock on a spacecraft. That's where 3D printing comes in. NASA is partnering with Jason Ballard's company Icon to pioneer 3D printing on the moon.

In late 2022, NASA launched the first in a series of Artemis missions. The next, with crew on board, is now scheduled for late 2025. And by the end of the decade, an Icon printer is supposed to fly to the moon to test print part of a landing pad. Jason Ballard, who once applied to be an astronaut but was rejected, can't wait.

Jason Ballard: If the schedule holds, or even approximately holds, the first object ever built on another world will be built with Icon hardware.

Lesley Stahl: He wants Icon to be the first company to make something on another world.

Corky Clinton: So do we.

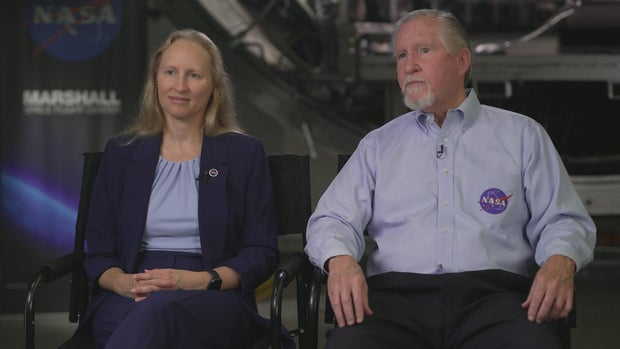

At Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, NASA scientists Jennifer Edmunson and Corky Clinton run a program called Impact.. spelled M-M-P-A-C-T.

Corky Clinton: Moon to Mars Planetary Autonomous Construction Technologies.

Lesley Stahl: Whoa. You people at NASA, you come up with these very, very (laughs) long names.

Corky Clinton: That's why we call it MMPACT. (laughs)

The key word there is autonomous.

Corky Clinton: We want to be able to make structures that we need without having to be tended by astronauts.

Jennifer Edmunson: If you're gonna have a truly sustainable presence on the lunar surface, you have to be as Earth-independent as possible.

NASA was interested in 3D printing, having looked at an early version almost 20 years ago. So when they heard about the progress Icon had made with their first houses in Austin, Corky Clinton traveled there to take a look.

Corky Clinton: Being an engineer, I spent a lot of my time going around and looking at the size of the beads and how they went around the corners, and I'll tell ya, I was really impressed with what they had accomplished.

Impressed enough that NASA gave Icon development money in 2020, and then, two years later, a $57 million contract.

Jason Ballard: Welcome to Spacelab, Lesley. This is where we figure out how to build on other worlds.

Ballard and Evan Jensen, who leads the project, explained the fundamental challenge.

Jason Ballard: To bring an object roughly this size from Earth to the moon's surface would be $1 million.

And think about--

Lesley Stahl: What-- wait, that size would be $1 million–

Jason Ballard: Correct. With current technology, this would take about $1 million to deliver to the lunar surface. And think of how many sort of brick-sized things we would need to do launch pad, landing pads, roads, habitats, We'll never have a moon base if we're gonna bring everything with us. So it was okay during the Apollo program to bring things with us. 'Cause we weren't staying, we were coming home. If we want to stay, we have to learn to live off the land.

Lesley Stahl: You have to learn to build it there and use the material–

Jason Ballard: Correct. Yeah.

Lesley Stahl: --from there.

Jason Ballard: That's right.

But that's no easy feat. It means using what's called lunar regolith, which covers the moon's surface, rather than concrete and water, as a building material.

Jennifer Edmunson: Regolith is made up of rock that has been pummeled over billions of years from asteroids, comets and things.

Lesley Stahl: Is it like sand?

Jennifer Edmunson: It's actually finer than sand.

Icon has a big tub full of simulated moon regolith, and they have invented and built a robotic system to 3D print with it.

Lesley Stahl: You're gonna build all those roads and buildings out of this?

Evan Jensen: That's correct. The robots will.

Jason Ballard: This is actually the mission that we are scheduled to fly.

As he pointed out in this rendering…

Jason Ballard: Our robotic arm with our laser system..

They've created a whole new way to 3D print -- with lasers. Instead of a nozzle squirting out soft concrete, a high-intensity laser beam will melt the powdery regolith, to transform it into a hard, strong, building material. they're running experiments now, using the laser to create a small sample.

Jason Ballard: Once that red light is on, we're hot.

Lesley Stahl: Oh.

Jason Ballard: Lots of power.

Martyn Staalsen: Here we go.

Jason Ballard: Here we go.

We watched on monitors as the arm got into position.

Martyn Staalsen: There's the laser.

Lesley Stahl: Oh. That white thing is the laser.

Evan Jensen: So it's melting right now-- It's going up to, say, 1,500 degrees Celsius.

Jason Ballard: It's gonna complete its second pass. You can see it emerging there. See the dark object on the screen? That's the object we just made with the laser.

They can add more regolith and laser again and again to build in layers to go as high as they want, which will be done remotely from earth. It takes hours to cool, so they showed me a sample they'd made days earlier.

Lesley Stahl: This is pretty darn hard.

Evan Jensen: That's our landing pad. You're holding it.

Lesley Stahl: I'm holding the landing pad?

Jason Ballard: That's exactly right.

Lesley Stahl: It's pretty cool. That's a scientific term.

Icon sends them to NASA, where they're blasted with this special plasma torch..

Corky Clinton: The torch will be about 4,000 degrees

To see if they can take the heat a landing pad would have to withstand.

Corky Clinton: See there.

Lesley Stahl: Oh, there it is.

The torch is so bright, you have to watch on a monitor.

Corky Clinton: That was it.

A few minutes later, out it came.

Lesley Stahl: Oh. It's just a little bit warm.

Corky Clinton: It looks good to me. I don't see any loss of material. I don't see any cratering.

Lesley Stahl: It survived the test?

Corky Clinton: Passed the test with flying colors.

The next test will be operating the entire robotic arm and laser..

Corky Clinton: We'll put in a large-scale simulant bed.

Inside NASA's giant thermal vacuum chamber, which mimics the moon's extreme cold, heat, and vacuum conditions.

Jason Ballard: This is sort of like--

Ballard's idea is to eventually send mobile 3D printers to the moon..

Jason Ballard: So this moves the printer around..

With a longer robotic arm sticking out of the top to print whatever is needed.

Jason Ballard: And then they would build the road and then they would build those habitats. Right?

And it wouldn't stop there.

Jason Ballard: If we can do it on the moon, we can do it on Mars. The moon is actually harder.

Lesley Stahl: It's harder?

Jason Ballard: Mars is almost in every way easier, except for it's so far away.

Easier, they agree, because for one thing, Mars doesn't have extreme temperature swings.

Lesley Stahl: Still, in my mind, it's science fiction. But in your minds, it's absolutely in the palm of your hand. It's going to happen.

Jennifer Edmunson: We can see the steps and the technology to get us there.

Lesley Stahl: Now, that's thrilling.

Corky Clinton: It's exciting.

Jason Ballard: Quality can't go backwards in Block 4.

Icon says trying to 3D print on the moon and Mars is helping with their work here on Earth. They are formulating new mixes to reduce the carbon footprint of their concrete.

Alex Le Roux: We think we will be there by end of year.

And they're trying out more radical architecture..

Jason Ballard: Quite complex shapes and geometries. Almost looks like ripples on the surface of water.

Patterned walls..

Lesley Stahl: Look at that–

Jason Ballard: --so this is-- this is-- a thing that a customer ended up really liking.

Dramatic flairs...as with this performing arts pavilion in Austin.

Woman: Watch your step.

And they're working on test printing domes.

Jason Ballard: There's something about arches, domes, and vaults that, like, lift the human spirit. But they're typically too expensive. In fact, they're so expensive, you usually only see them in, like, civic buildings or religious buildings.

Lesley Stahl: Domes? Oh, yeah–

Jason Ballard: Domes, arches–

Lesley Stahl: Churches.

Jason Ballard: --vaults. I see the face you're making. Every human being loves being in one of those buildings–

Lesley Stahl: Oh, of course. They're gorgeous.

Jason Ballard: What if having those was available to everyone, and it was faster and cheaper than the kinda roofs we have today?

And this year, as in these renderings, they'll be printing round hotel rooms in Marfa, Texas...

Lesley Stahl: These are rooms–

Jason Ballard: Yes, ma'am.

Lesley Stahl: --that you would stay in--?

Jason Ballard: That's correct. And so, like, here's one.

Lesley Stahl: Oh.

Jason Ballard: That sort of curve sort of continues down through the roof into the room itself and sort of creates a stairway onto a bed platform.

And they'll also be printing futuristic-looking designer homes.

Jason Ballard: You see a bedroom on that end with a shower and a bedroom here. And here's some renderings of the interior.

Lesley Stahl: Wow.

Jason Ballard: Right? It gets you goin', doesn't it?

Lesley Stahl: Do you think it'll ever be possible to print out, like, a 20-story apartment building, -- or even-- a skyscraper?

Jason Ballard: Oh, yes. In fact the architecture for our next generation of printer will be, like, more or less prepared for that.

Jason Ballard: Ladies and gentlemen, I'd like to formally introduce you to the next generation print system Phoenix.

Just this spring at Austin's South by Southwest festival, Ballard unveiled the "next generation" of printer.. called Phoenix..

Jason Ballard: And by a mile, this is the most sophisticated and challenging engineering we have ever attempted. This is like our version of landing rockets.

It's a robot with a single, 75-foot-long arm, similar in design to the one Icon is developing for the moon, which they say enables printing multiple-story buildings, allows for greater flexibility, and can print faster than their current printers, which will still be busy. In another partnership with Alan Graham, Icon is breaking ground on 100 more 3D printed homes for the formerly homeless at Community First Village.

Lesley Stahl: A lot of what he's doing here is good for PR. So how much is genuine, and how much is just doing things to promote his business?

Alan Graham: Well, I think 100% is genuine. And I think 100% is-- promoting his business. He believes that they are on the cusp of technology that's gonna have a dramatic impact-- on the world. Otherwise, I don't think he'd be doing it.

Jason Ballard: You have to remember, there's a tremendous amount of human suffering every year, and every five years, and every decade that goes by where we're not getting shelter right. There are over a billion under-sheltered people, which means if we built a million homes a year, it would take 1,000 years. That is 950 years too long.

Jason Ballard: This is one of the most foundational things that we have to get right, or the future cannot be exciting. L--like, forget all the other stuff. You might--get flying cars-- (laugh) w-- the future cannot be exciting if we don't get human shelter--right.

Lesley Stahl: We're living at time, right now, where a lot of CEOs have been caught over-promising, hyping.

Jason Ballard: Mm-hm.

Lesley Stahl: I'm thinking of Theranos.

Jason Ballard: You're absolutely right. And it-- and it-- it's-- it's-- it's a tougher thing than you know. Because part of the job is to get your investors, get your team, and in our case the world-- to believe the things you are saying. Except the things you are saying don't exist yet.

Lesley Stahl: Yeah. Oh, boy–

Jason Ballard: You-- you need to get them to believe.. So it's hard to know-- like, even in this interview, I actually haven't yet told you all the things I believe we're going to do, 'cause I'm, like, measuring myself.

Lesley Stahl: Give us one example. (laughs) Something wild.

Jason Ballard: I mean, in the future, I think most buildings will be designed by AI, most projects will be run by software, and almost everything will be built by robots. And I don't think that's that far away.

Lesley Stahl: I at my age find that very depressing--

Jason Ballard: Haa–

Lesley Stahl: --but I'm sure young people don't–

Jason Ballard: --well, lemme-- yeah, no, no. That world, housing will be more abundant, more affordable, more beautiful. It will make this version of housing look depressing by example.

Lesley Stahl: You know that expression, "If it seems too good to be true, it is?"

Jason Ballard: Or-- I do know that expression. But cars, and airplanes, and moon landings seemed too good to be true for a moment as well. And so, like maybe the only proof I can give you is, like, I'm betting my life on it. Like, I have this one precious life to live, and I'm using it to do this. And if I could think of a better way, I'd be doing that instead, or I'd go fishing. Like, this is so hard. (laughs)

Lesley Stahl: And you like fishing.

Jason Ballard: I love fishing.