Researchers from The Australian National University have proposed a new method for desalinating water that avoids many of the unwanted side effects of traditional desalinating techniques and that reduces the energy required by about 80%.

Freshwater is becoming a critical issue in many locales around the world, and some are already relying on desalination—extracting freshwater from ocean water.

About one-third of all freshwater discharges are now used by humans, projected to go to one-half by midcentury, especially in regions such as Israel, Mexico City, India, southern California and many others. Arguably, water availability will be the most serious crisis humanity faces this century, made worse as climate change melts snowpack, increases evaporation from surface water, alters precipitation patterns and amounts and increases the amount of water held in the atmosphere.

A 2018 report from the World Bank found that about 300 million people in over 150 countries around the world rely on desalination at an energy cost of 3 kilowatt-hours per cubic meter (kWh/m3), down by a factor of 10 since 1970. Still, desalination accounts for one-fourth of the energy used in the provision of water, requiring about 100 billion kilowatts-hours of energy in 2018.

Desalination techniques to date are either material-based methods, such as reverse osmosis that uses high pressure to separate molecular species in water, or thermal methods, such as solar based evaporation or freeze desalination.

But these systems can take in and kill smaller ocean life by heat, stress or chemicals, or pin larger marine life against intake screens. And they leave behind brine—water with a very high salt content of over 30% (ocean water contains about 30 to 35 grams of salt per kilogram of water, mostly NaCl) that is discharged back into the ocean, where it sinks to the bottom and harms ecosystems.

These traditional desalination facilities require expensive materials that must be cleaned and maintained, as they are prone to membrane fouling, corrosion and degradation, as well as energy requirements of 3 to 7 kWh/m3 for reverse osmosis and up to 100 kWh/m3 for other methods. They are suitable for urban and industrial environments, but too large and costly for developing nations or in rural and remote regions.

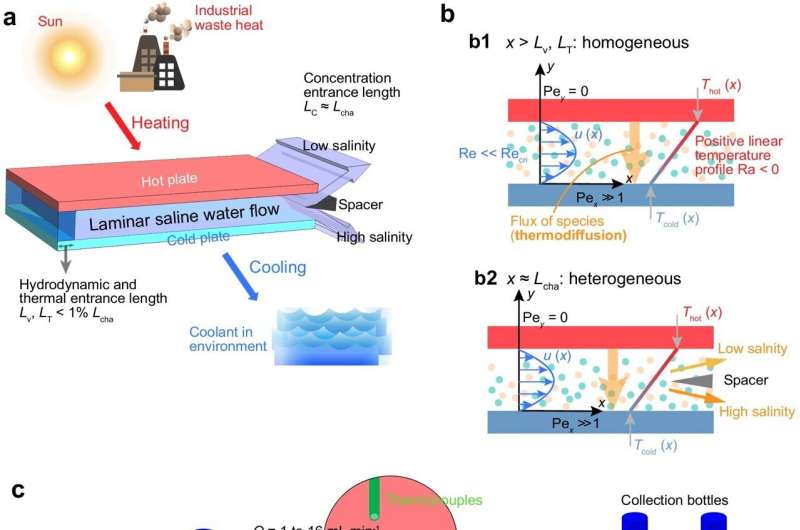

The new method published in Nature Communications relies not on electricity, but can use low-grade heat from sunlight, or heat that is a byproduct of an industrial process. It utilizes thermodiffusion, a phenomenon where salt transfers to the colder side of a smooth temperature change (temperature gradient) from hot to cold. The water remains in the liquid phase throughout.

Led by Ph.D. candidate Shuqi Xu, the research team pushed seawater through a narrow channel under a top plate that was heated to over 60°C and over a bottom plate cooled to 20°C. Both temperature values for the plates can be extracted from the environment, as discussed above. Low salinity water emerged from the water in the top region of the channel, and high salinity water from the lower part of the channel.

In the group's experimental setup, the channel was a half-meter long, one millimeter high with flow rates between 1 and 16 milliliters per minute.

After a single pass through the channel, cooler, saltier water was removed, and warmer, less saline water was directed back through the channel. Each pass saw salinity decrease by 3%. After repeated cycles, the salinity of seawater can be reduced from 30,000 parts per million (ppm) to less than 500 ppm.

"Our dream is to enable a paradigm shift in desalination technology, based on methods that can be driven by low-temperature heat in our surrounding environment," said Juan Felipe Torres, a professor at Australian National University and lead chief investigator for this research.

"To the best of our knowledge, thermodiffusive desalination is the first thermal desalination method that does not require a phase change. It's operated entirely in the liquid phase, and what's more important is that it does not require membranes or other types of ion-adsorbing materials to purify water."

Thermodiffusive desalination is free of fouling, "which could be a game-changer in the way we conduct large-scale desalination," continued Torres. Agriculture, which uses about 69% of the world's freshwater, needs water that is desalinated to about 95% of its base value.

Since their proof-of-concept, the group is now building a larger, multi-channel device to desalinate sea water for use on the southwestern Pacific island of Tonga, which is in the midst of a severe drought. There the apparatus will be powered by a solar panel the size of a human face.

Torres sees thermodiffusive desalination as vital for developing countries, many of whom are experiencing the worst of climate change, by decentralizing the desalination process and bringing water security to these areas.

More information: Shuqi Xu et al, Thermodiffusive desalination, Nature Communications (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-47313-5

© 2024 Science X Network

Citation: New, electricity-free desalination method shows promise (2024, May 20) retrieved 20 May 2024 from https://techxplore.com/news/2024-05-electricity-free-desalination-method.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.