U.S. officials are worried that their hopes of developing a green industrial base will be derailed by China. This is not an unreasonable concern, but the current focus on looming “overcapacity” in green tech (and other sectors) is both confusing and unhelpful.

Instead, the focus should be on underconsumption—both in China, and elsewhere—which is what actually threatens the viability of the green transition, as well as global economic and financial stability.

This is how Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen publicly framed the issue in Beijing, after days of private meetings with top Chinese officials:

There are features of the Chinese economy that have growing negative spillovers on the U.S. and the globe…We are seeing an increase in business investment in a number of “new” industries targeted by the PRC’s industrial policy. That includes electric vehicles, lithium-ion batteries, and solar. China is now simply too large for the rest of the world to absorb this enormous capacity. Actions taken by the PRC today can shift world prices. And when the global market is flooded by artificially cheap Chinese products, the viability of American and other foreign firms is put into question.

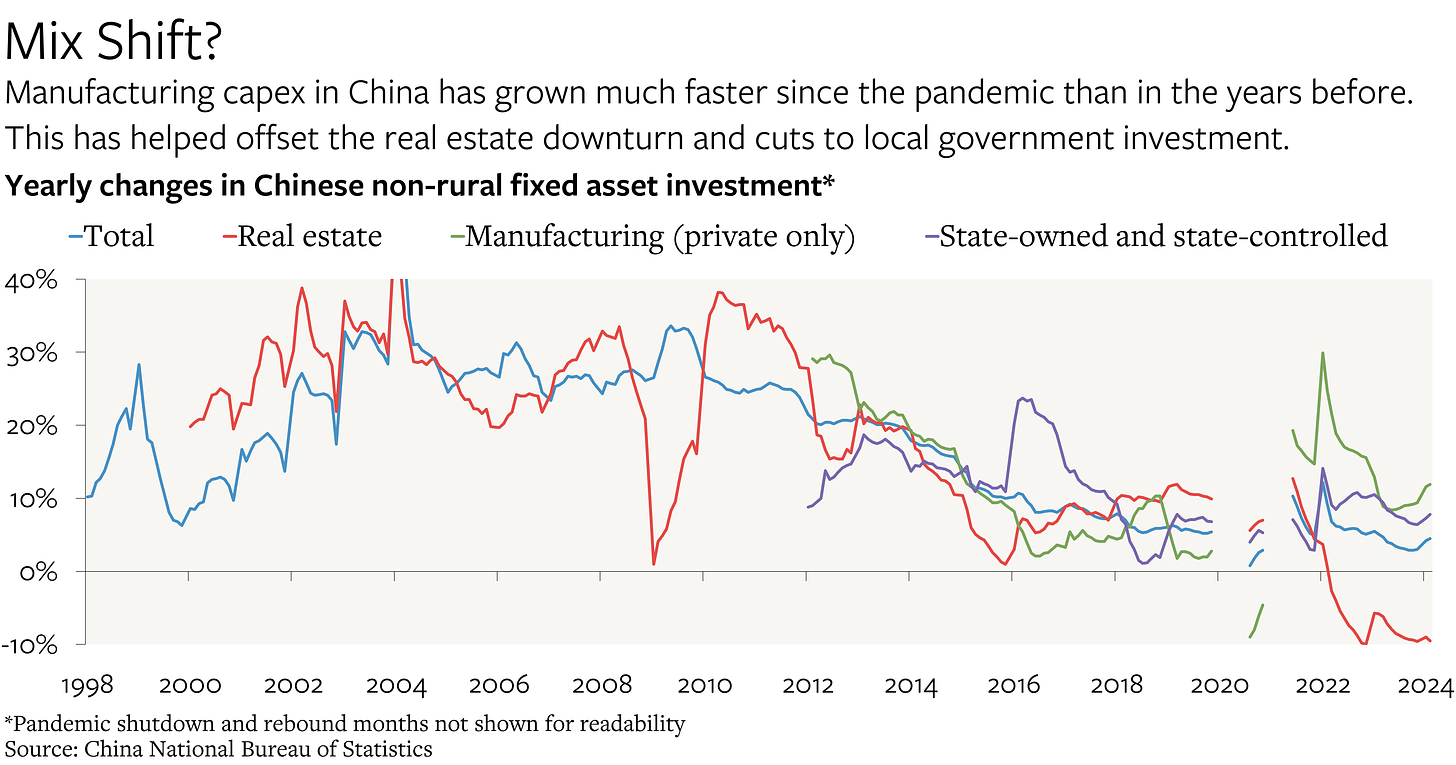

To be fair, fixed asset investment in China’s manufacturing industry has been growing relatively briskly over the past few years, especially relative to the average growth rate in 2016-2019. That has helped offset some of the recent weakness in real estate and local government infrastructure investment.

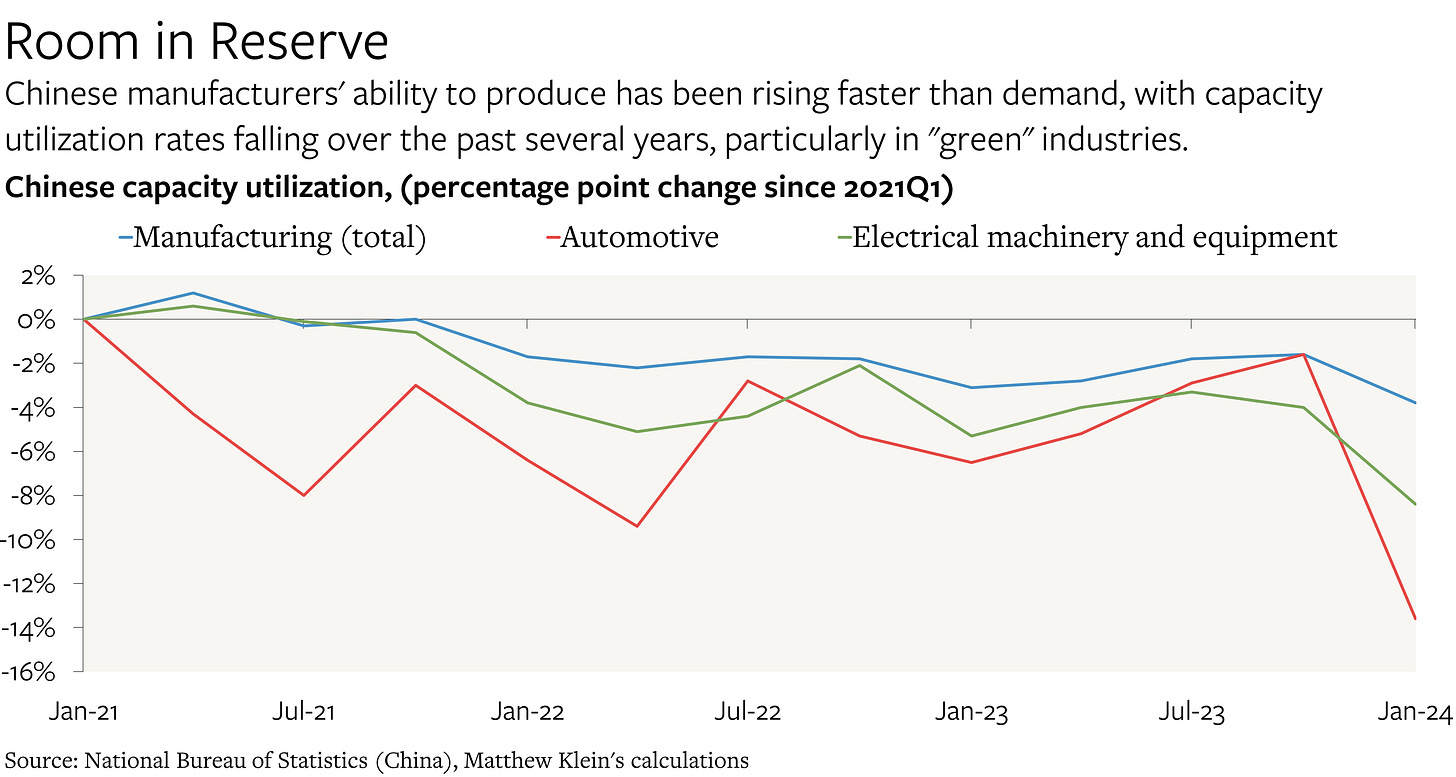

At the same time, Chinese estimates of capacity utilization—which only go back to 2021Q1—show that manufacturers, particularly those in green industries, seem to be increasing their capacity to produce far faster than their actual production.

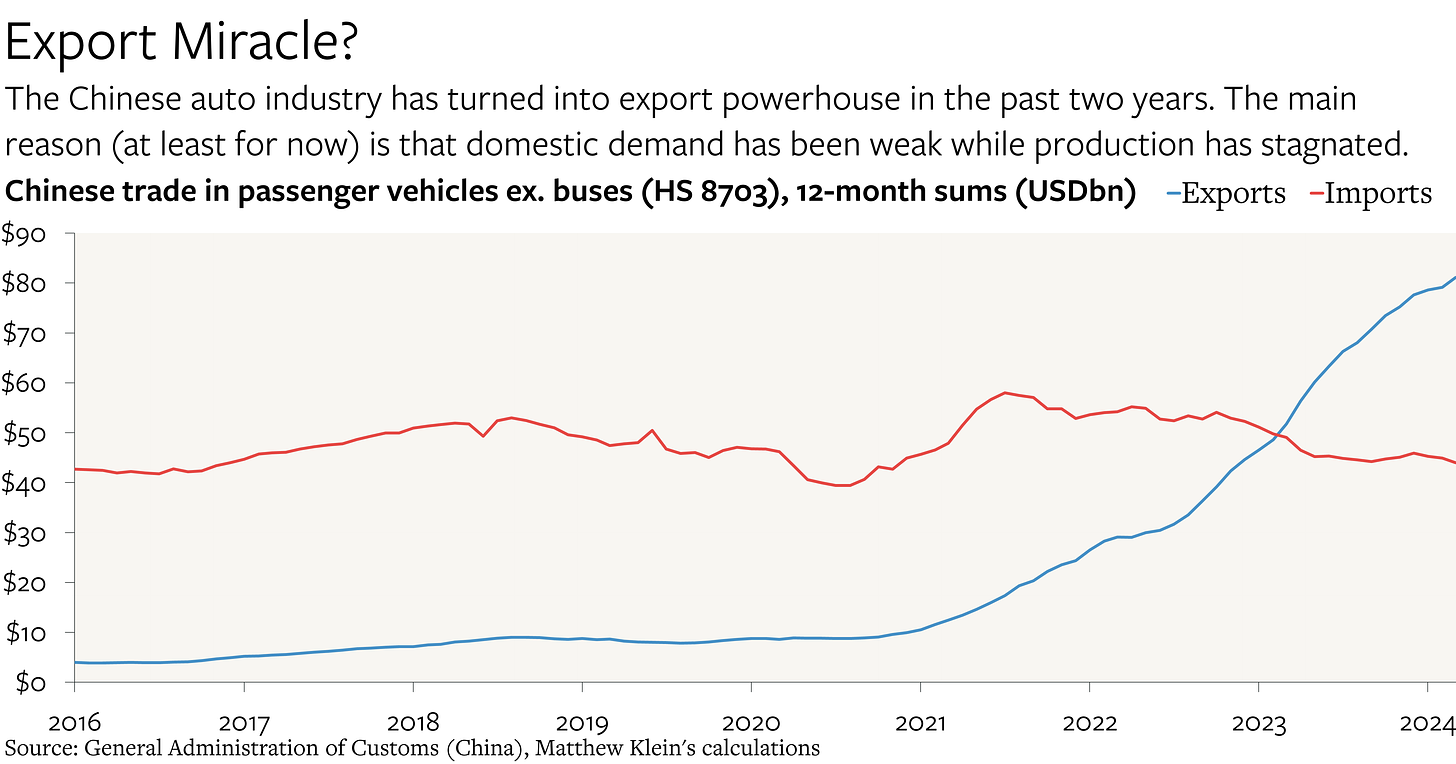

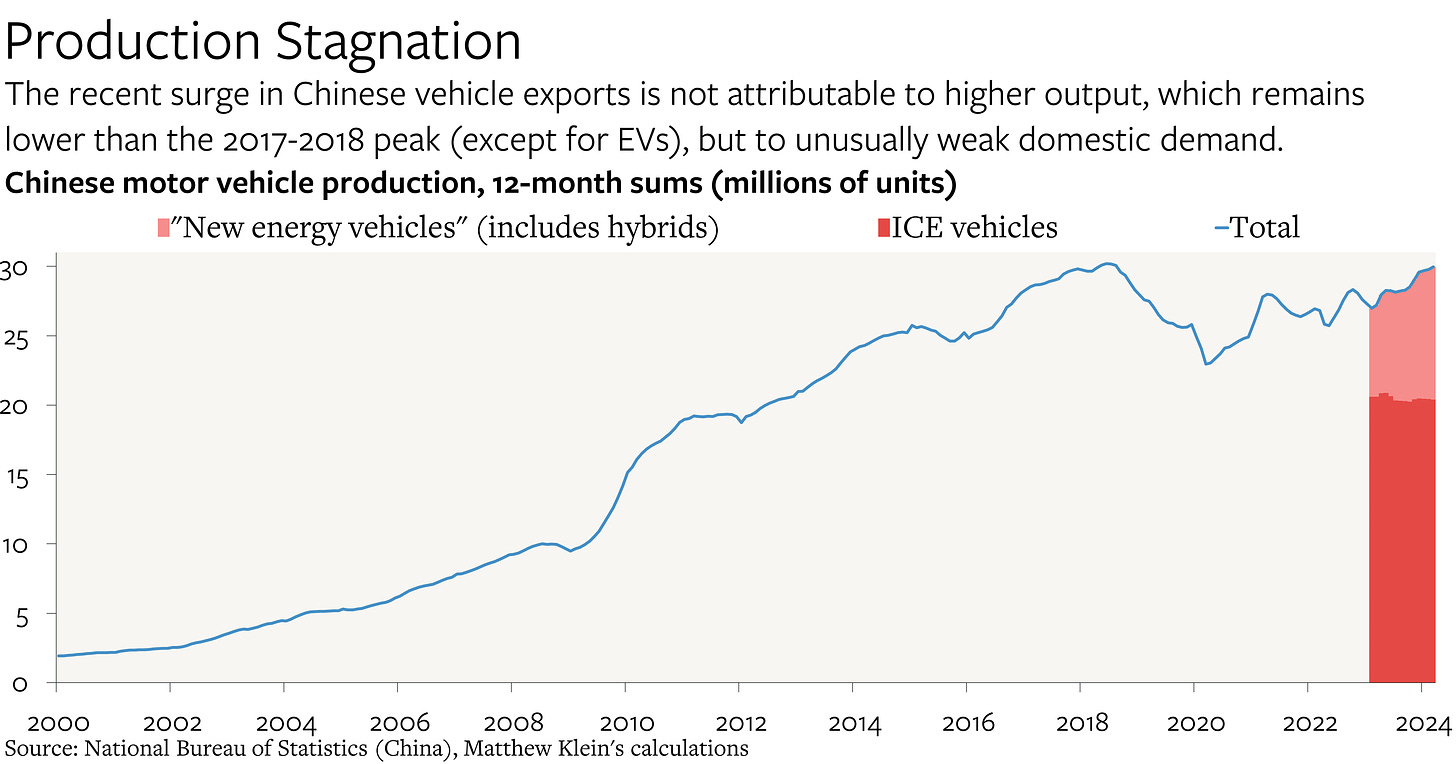

Meanwhile, this is coinciding with a surge in the value of Chinese exports of motor vehicles, which are now running at more than $80 billion/year, up from $9 billion/year as recently as 2019. China has flipped from a major source of net demand for finished vehicles into a major source of net supply.

However, this narrative is missing some important details.

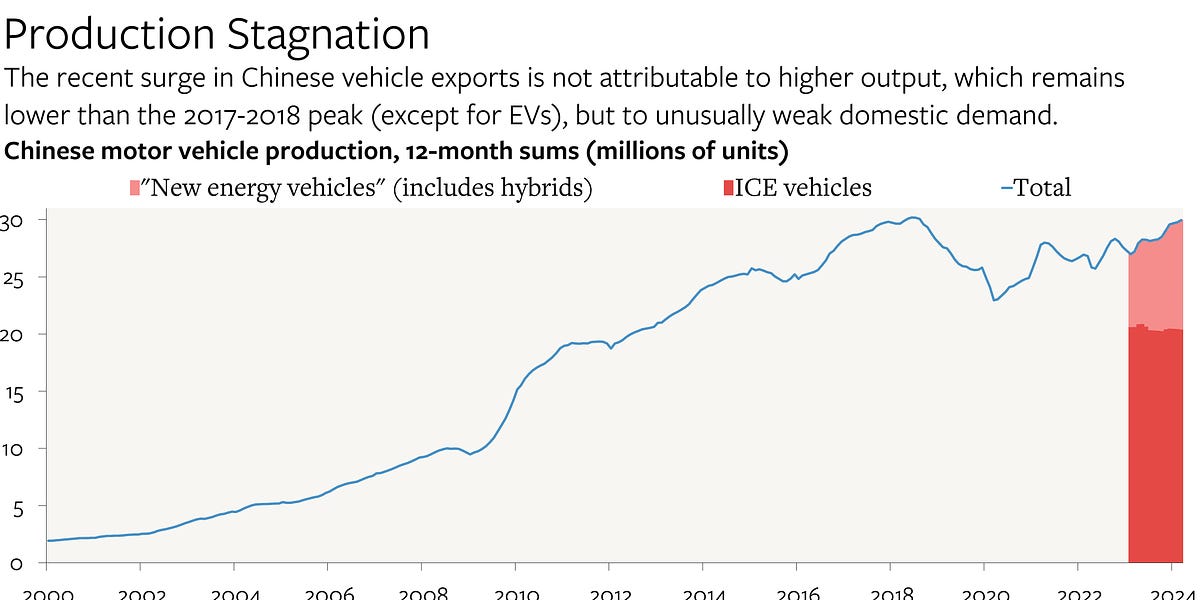

While China’s motor vehicle exports have surged, flipping the trade balance from a sizable deficit into a large surplus, total Chinese production of motor vehicles has been much less impressive. In fact, the number of finished vehicles assembled recently is slightly below the prior peak in 2017-2018. And while output of “new energy vehicles”—a category that includes hybrids and plug-in hybrids, as well as pure electric vehicles—has been ramping up quickly, it is still relatively small, which means most production (and exports) are old-fashioned fossil-powered cars and trucks.

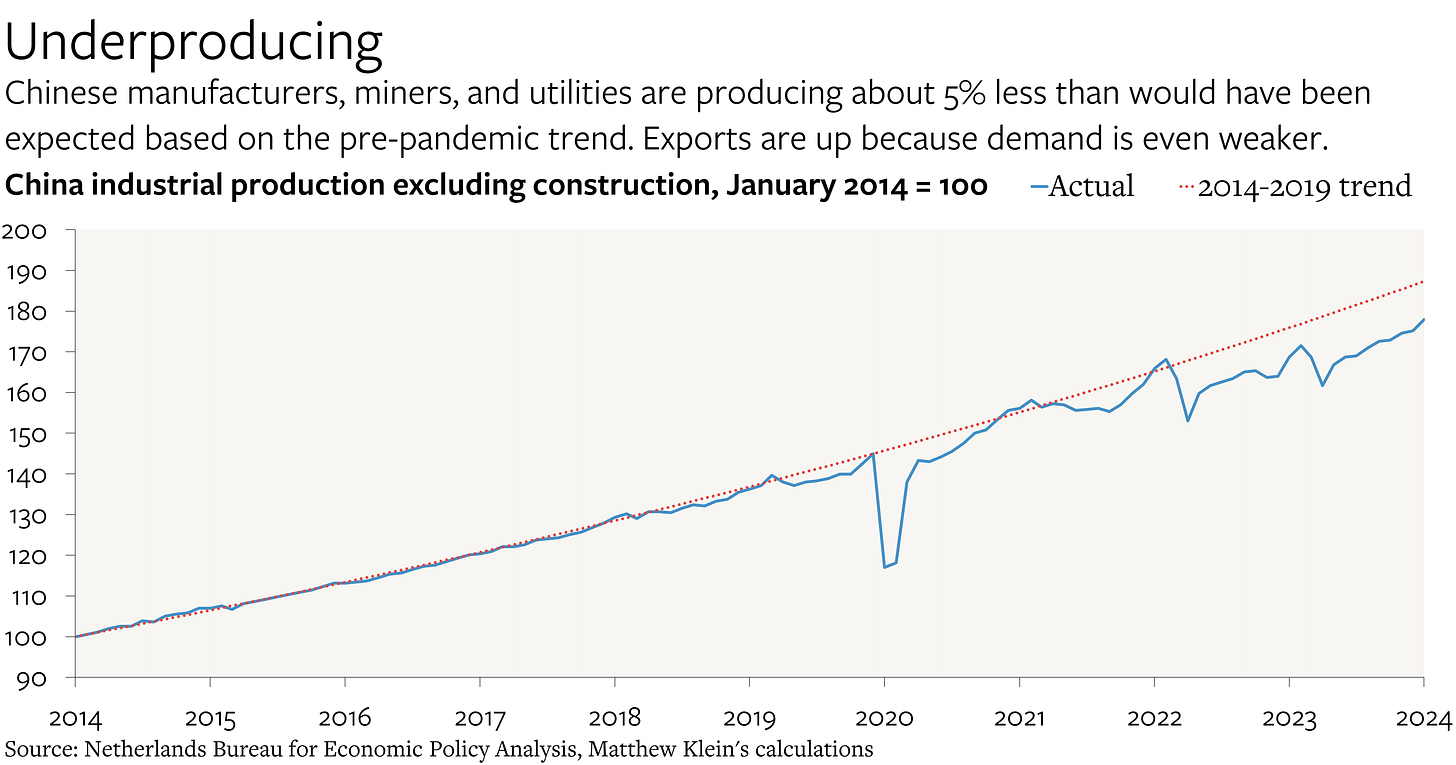

Zooming out, total Chinese industrial production has been running about 5% below the 2014-2019 trend since 2022. While some of that gap may reflect the rentrenchment of foreign demand for durable goods after the initial panic-buying during the pandemic, it also coincides with the harsh imposition of “Covid Zero”, which squashed Chinese domestic consumer spending. Tellingly, the end of those restrictions does not seem to have led to any catchup in either retail purchases or industrial production.

As it happens, one of the retail spending categories with the biggest shortfalls is motor vehicles. Once consumer-facing incentives were withdrawn in 2018, spending growth stalled. In nominal terms, Chinese retail spending on vehicles has grown at an average yearly rate of just 2% over the past six years. Spending in the past 12 months has been a third lower than what might have reasonably been expected based on prior trends.

That might be justifiable if the Chinese market were saturated with EVs, but it is not. According to China’s Ministry of Public Security, Chinese only own about 20 million “new energy vehicles”, out of 336 million total cars and trucks.1 China may have a high share of hybrids and EVs on the road relative to other major economies,2 but that share is still extremely low relative to the Chinese government’s stated climate objectives.

Besides which, there is also good reason to think that China’s overall motor vehicle ownership rate will rise as incomes converge with those in richer countries. For comparison, Mexico, a country with about 1/10 the population of China and similar incomes, has 48 million cars and trucks on the road. The U.S. has about 270 million registered cars and trucks, despite a population only 25% as large as China’s.

From this perspective, current Chinese production of 10 million NEVs/year is far too low for China’s own domestic needs, properly understood. Even if every new Chinese NEV were replacing a Chinese fossil-fuel vehicle—which is an unreasonable assumption, since many buyers are replacing older NEVs, because total car ownership is rising, and because some NEVs are exported—it would take 31 years at current rates to turn the Chinese vehicle fleet green. That also means that Chinese EV production is far too low to ensure sufficient supply of cars and trucks for the many societies that lack the ability or inclination to produce their own. The same logic applies to the rest of the supply chain, such as batteries and electricity transmission equipment.

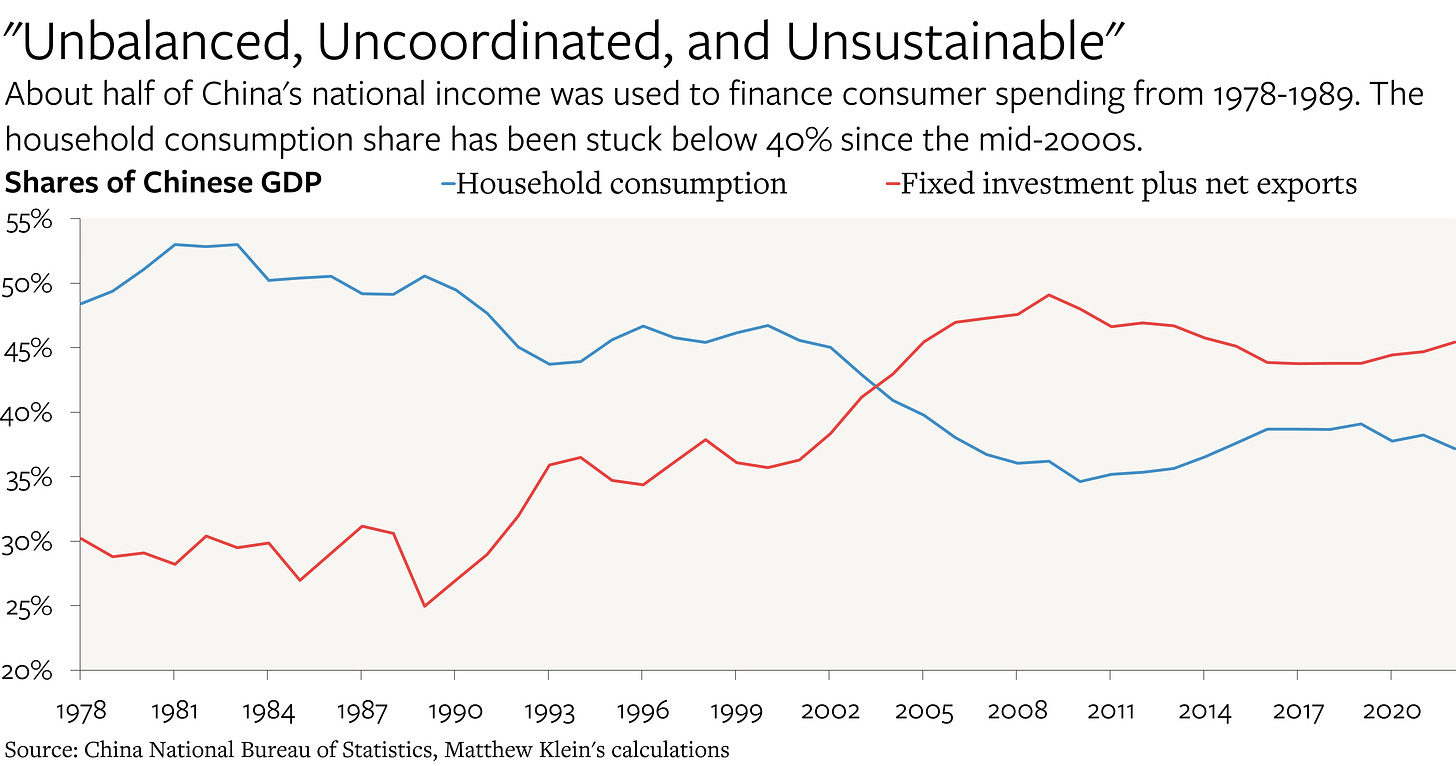

This would be obvious if Chinese demand for all goods and services were not structurally suppressed by the party-state’s anti-consumer political economy. Chinese goods are “artificially cheap”, as Yellen put it, because ordinary Chinese are deprived of spending power commensurate with the value of what they produce. Only 37% of China’s national income is spent by Chinese households on goods and services. That level is lower than anywhere else in the world—except for a few small tax havens and commodity hyperexporters when prices are high. For Chinese nonfinancial corporations, employee compensation is only worth about 44% of gross value added, whereas the equivalent measure of the labor share in the U.S., Europe, and Japan is ~60%.3

To use Yellen’s words, “the viability of American and other foreign firms is put into question” at least as much by Chinese underconsumption, which reduces Chinese imports and encourages Chinese firms to dump wares abroad, as by any “competitive” advantage that Chinese companies have in their home market.

The implication is that the real threat to green industry is weak demand. Yet policymakers seem to mostly ignore this, perhaps because they believe that they have already done as much as they need—or as much as they can, anyway—to encourage people to buy green goods. Given that constraint, they now fear that (subsidized) producers may end up selling more than consumers want to buy, which is why some now feel compelled to (try to) suppress foreign production for the sake of protecting domestic employment.

That instinct is understandable, but it will lead us to a poorer—and dirtier—world. Instead, we should shed the zero-sum mentality that underpins concerns about China (and the similar but even more misplaced European concerns about the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act) and focus on how we can increase demand and supply at home and abroad.

This reframing of the problem might not lead to many differences in actual policies, but it should help clarify our goals and motivations. In particular, the U.S. and others might still end up needing to deploy preferential subsidies to sustain their domestic productive bases in the face of Chinese underconsumption. Not because Chinese produce too much, but because we might want to protect our producers from what happens when Chinese are deprived of the chance to benefit from their own hard work.4

Chinese producers might still end up specializing in making green goods for export when all is said and done. There would be nothing inherently wrong with that, although it implies some combination of lower production of other goods for export and higher imports of goods and services from the rest of the world. The problem is that China’s current green goods export boom is happening in large part because Chinese demand is still so weak.

It would be absurd to claim that the green transition requires that Chinese workers be exploited. Yet that seems to be the assumption among many who argue that Chinese exports of green goods should be allowed to displace production in the rest of the world without any offsetting increase in Chinese demand.

But there is a better way. People in China and people in the rest of the world have a common interest in greening their economies while promoting prosperity. Material deprivation still afflicts much of the world, including in the rich countries. The problem is not “too much stuff” but not enough stuff. The question is how to encourage as much production as possible in a financially, environmentally, and politically sustainable way.

As Yellen put it later in her speech:

Addressing these imbalances in an appropriate way will not only be good for the U.S. and the world. It will also be good for China’s long-term productivity and growth. Importantly, we have and will continue to emphasize that our concern about overcapacity is not animated by anti-China sentiment or a desire to decouple. Rather, it is driven by a desire to prevent global economic dislocation and move toward a healthy economic relationship with China.

Her counterparts may or may not believe her, but she will be more convincing if she focuses less on “overcapacity” and more on underconsumption.