A recent analysis by Helene Pleil, research associate at the Digital Society Institute (DSI) at ESMT Berlin, alongside colleagues from Technical University Darmstadt, outlines that rapid technological progress, a lack of political will and uniform definitions, as well as the dual use of cyber tools, are the main challenges facing effective cyber arms control which is vital for foreign and security policy. As cyberspace is increasingly used in conflicts, cyber arms control needs to be addressed as well.

Pleil and her colleagues conducted the literature review on challenges and obstacles facing the development of arms control measures in cyberspace. This review, published in Zeitschrift für Außen- und Sicherheitspolitik and augmented by expert interviews, identifies key hurdles in developing robust cyber arms control measures.

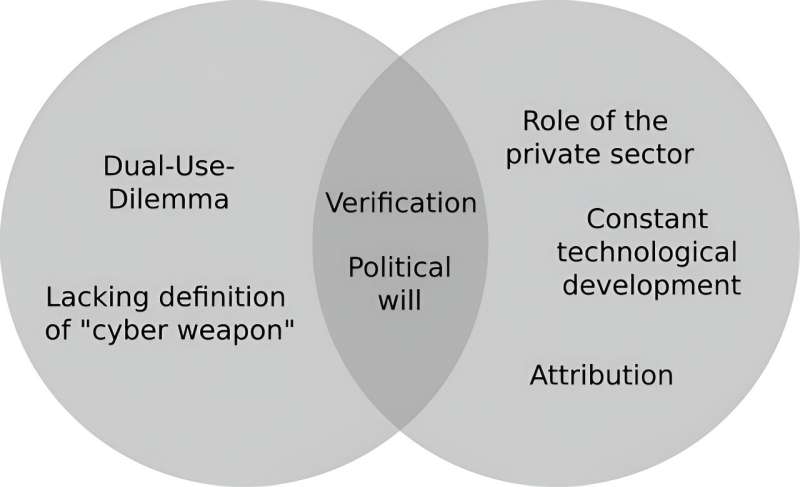

The following challenges were identified:

- Lack of definitions. A fundamental challenge for establishing arms control in cyberspace is the lack of clear, uniform definitions of key terms, such as "cyberweapon," especially since the conventional definition of a weapon does not truly capture a "cyberweapon." It is difficult to agree on what would be controlled in an arms control treaty if what you want to control cannot be explicitly defined.

- The dual-use-dilemma. For example, a computer, USB stick, or software can be used for civilian as well as military purposes. Therefore, no clear line can be drawn between these different use scenarios, which is why the products cannot be banned in fundamental terms for arms control. You can ban nuclear weapons, but you cannot ban USB sticks or computers.

- Verification. Finding suitable verification mechanisms to establish arms control in cyberspace is extremely difficult. For example, for cyberweapons, it is not possible to count weapons or ban an entire category, as has been the case with arms control agreements for traditional weapons.

- Technological progress. Tools and technology for cyberattacks are changing rapidly. This means the development of new weapons outpaces regulatory efforts; by the time a regulation is discussed, the technology used has advanced.

- Role of the private sector. Due to the dual-use factor, states do not have sole control over means used as weapons, but non-state actors also have ownership and operational rights in this domain. Thus, the private sector would need to be involved and committed for arms control to be effective.

- Lack of political will. Political will is crucial for establishing arms control measures, but states are reluctant to do so within cyberspace. Countries are just discovering the strategic value of cyber tools and have diverging interests. Complying with a new treaty on the use of cyber tools risks them missing out on potential advantages

- In addition, the current geopolitical climate is another major challenge.

"According to the literature and experts, neither the control of a cyberweapon nor any other technological regulation for cyberspace will work," states Pleil. "Instead, the focus must be on banning certain actions, since experts do not see any chance for verification mechanisms, especially because of the high level of intrusion that would be required."

Traditional measures of arms and weapon control cannot be simply applied to cyberweapons. Instead, new alternative and creative solutions must be created. By defining and sanctioning the uses of weapons, rather than the tool itself, this would allow agreements to be made and upheld, regardless of the pace of technological development, for example.

More information: Thomas Reinhold et al, Challenges for Cyber Arms Control: A Qualitative Expert Interview Study, Zeitschrift für Außen- und Sicherheitspolitik (2023). DOI: 10.1007/s12399-023-00960-w

Provided by European School of Management and Technology (ESMT)

Citation: Sanction the use of cyberweapons, not the weapons themselves, concludes expert review (2024, April 5) retrieved 5 April 2024 from https://techxplore.com/news/2024-04-sanction-cyberweapons-weapons-expert.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.