If there’s one thing you can count on in sports, it’s the desire of a certain segment of the media to rehabilitate their favorite players and coaches, no matter the harm done. There was the infamous Adam Schefter softball interview with Greg Hardy shortly after he was accused of doing this to his then-girlfriend. In the days before he was accused of sexually assaulting an Uber driver, I recall several pieces touting how much Jameis Winston had “matured” since he was accused of assaulting another woman in college. And, of course, far more glowing pieces have been written about Peyton Manning than were ever written about the allegations that he sexually assaulted a trainer in college. Neither Hardy, Winston nor Manning have ever been convicted of the allegations against them.

NBC hiring Snoop Dogg for 2024 Olympics in Paris is a major win

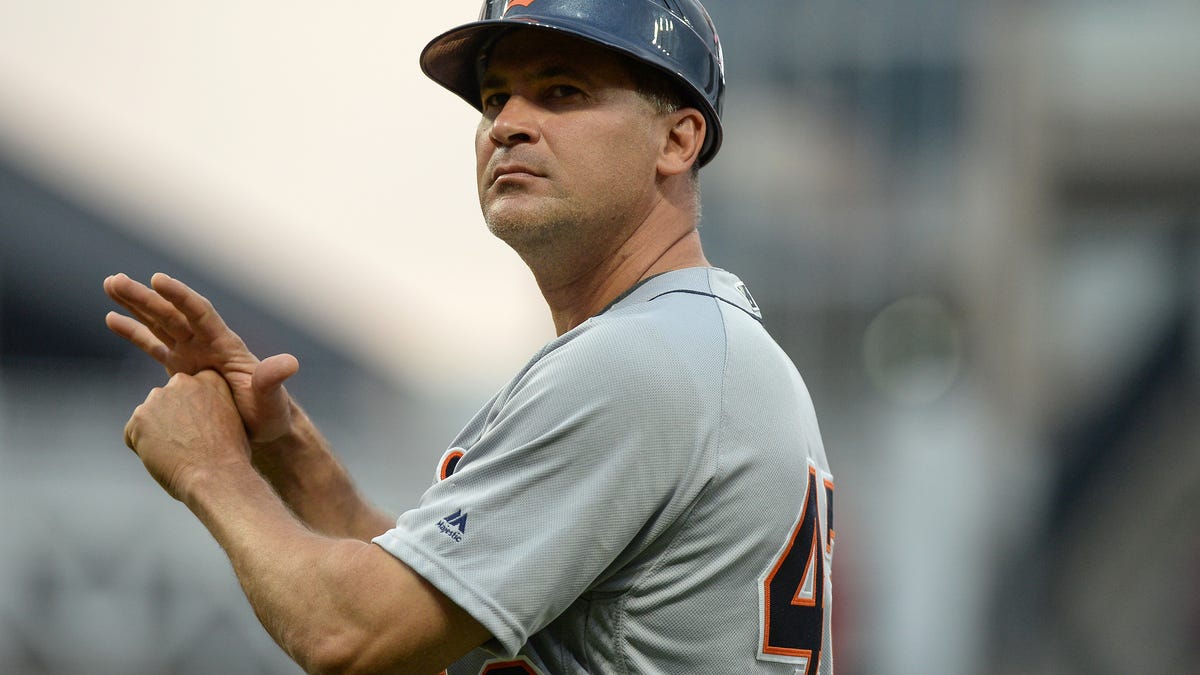

Enter Omar Vizquel.

When we last caught up with Vizquel, he had been fired by the White Sox Class AA team in Birmingham, Ala., after an internal investigation by the team, prompted by a lawsuit that accused Vizquel of sexually harassing a 22-year-old batboy with autism. Among other things, the batboy alleged that Vizquel was “sexually aggressive” with him and that he once demanded the batboy wash his back in the locker room shower. Vizquel settled the case out of court in 2022. Prior to that, Vizquel had been arrested for, but not charged with, domestic violence against his ex-wife, Blanca, who said Vizquel had physically abused her on multiple occasions. Vizquel denied the allegations and was not prosecuted for domestic abuse.

Given the allegations against Vizquel, it’s curious that anyone would be willing to give him cover to rehabilitate his image, but this is sports media and, particularly when allegations of violence against a woman are involved, there never seems to be a shortage of dudes willing to listen to “his side of the story” and write the inevitable puff piece, which is exactly what USA Today’s Bob Nightengale did for Vizquel.

Nightingale’s piece is rife with vivid imagery of Vizquel’s pain — how sad he is to see all his friends being involved in baseball when he’s left out in the cold, how he once spent three days in a room with only a glass of water (what?), that at one point, he didn’t even know what day it was (welcome to the week between Xmas and New Year’s, Omar). I suppose all of this was designed to make me empathize with Vizquel and start thinking he should get another chance, but there was nothing included in this piece that made me say anything other than “So?”

I don’t mean to pick on Nightengale — these kinds of restorative pieces on players’ images are always around. Like I said, there has never been an athlete accused of anything that sportswriters weren’t dying to write the “comeback” piece about. In part, I think, because what actual domestic abuse looks like, what sexual assault looks like, what sexual harassment looks like, are amorphous ideas to those who haven’t been in the trenches. Adam Schefter, who as far as I know is not trained in any way in the dynamics of domestic abuse, had no business interviewing Greg Hardy — he didn’t know what questions to ask. When a player like Ray Rice, who was honored by the Ravens on Sunday for reasons still not understood by me, goes to anger management counseling and then a PR tour, too many sports reporters simply accept that he’s done everything he could do. But someone with knowledge of the cycle of domestic abuse would ask different questions: “Did you ever go to batterer’s intervention counseling? For how long? Did you go to group therapy with other abusers or were you one-on-one with a counselor? You sat silently by while your wife, Janay, apologized for “her role” in you punching her in the face in an elevator. Do you still believe she “played a role” in your decision to hit her? What did you learn about power and control while in therapy? Do you now feel less of an urge to control everything around you? All of these represent axioms long understood by those in the domestic violence community (abuse is not about anger, but power and control, victims often recant their stories based on fear of the abuser or the consequences to the family, group therapy batterer’s intervention is perhaps the only form of treatment that has been proven effective for abusers, etc), but not well-known by the general public, including sportswriters.

I don’t mean to suggest that sportswriters shouldn’t interview subjects who have been accused of violence, only that educating ourselves on some of the ins and outs of topics like domestic abuse and sexual assault is mandatory before conducting the interview. After all, domestic abusers, in particular, are well known for charming friends and family into believing they’re innocent. (Which is why group therapy with other abusers is the recommended treatment — they can call each other out on their deception.) I often wonder if reporters talk to experts in domestic abuse or sexual harassment before coming up with a list of questions and strategies for interviewing a player accused of such things. They should.

Nightengale’s piece goes on to talk about how accepted Vizquel felt at Ronald Acuña Jr.’s MVP celebration, but how sad he feels about his life in Houston. How hurt he was because he wasn’t among the players the Mariners celebrated during the All-Star Game. That the Guardians didn’t allow him on the field to honor his former teammate, Manny Ramirez. That more than one MLB team pulled his invitations to appear at youth camps.

To which, again, I say “So?” When you’ve been accused of sexually harassing an autistic man and beating your ex-wife, a lot of people will decide not to associate with you, and if Vizquel was an ordinary citizen instead of a perennial Gold Glove winner, anyone who heard about the allegations against him would say “Good. You reap what you sow.” But for some reason, when it comes to men who play sports, there is a line out the door of people demanding the athlete’s second chance, as if the logical consequences of his actions are unfair.

Noticeably lacking from the Nightengale piece is any kind of introspection on Vizquel’s part. There is no self-reflection, no details of what Vizquel might have done to take a long, hard look at himself and dedicate himself to improvement. Instead, we get dozens of paragraphs of Vizquel whining and crying that he’s not the guy portrayed by the media (of course), and that no one listened to his side of the story, which I’m fairly confident is not true, given that there were investigations into both the allegations of sexual harassment and domestic violence.

Of course, there will be lots of men screaming (there always are) that Vizquel got a raw deal and should be back in baseball, but nothing Vizquel said in the USA Today piece convinces the reader of anything other than that Vizquel sees only himself, not his ex-wife or the 22-year old batboy, as the true victim. And that tells me everything I need to know about Omar Vizquel.