Weeks after reports of a mysterious new virus began to emerge in the central Chinese province of Hubei, the authorities there suddenly changed how they determined who was infected.

It led to a significant spike in numbers - only because doctors are now counting patients who are diagnosed in a clinic and not just those who have taken the test.

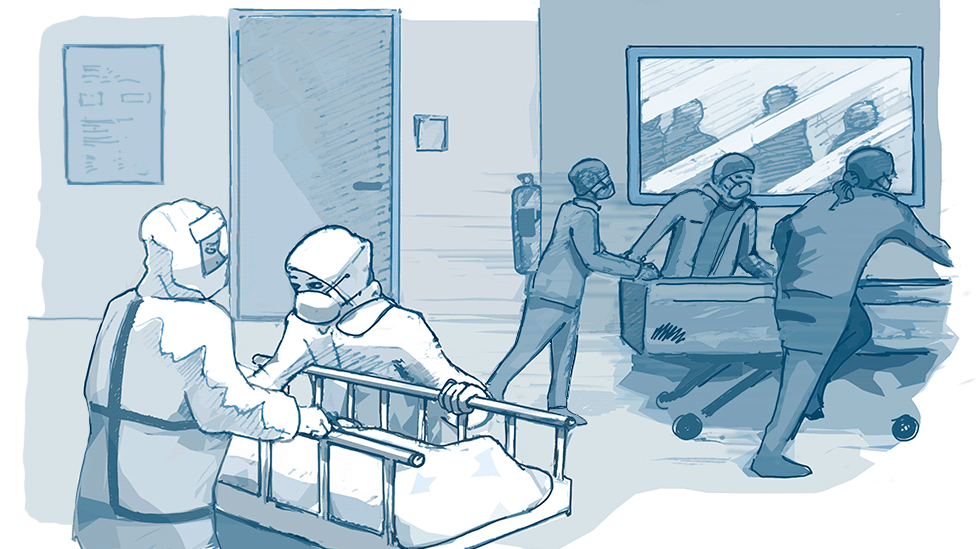

But in those early days, the rapid spread of the virus through the city of Wuhan, combined with a shortage of hospital beds, meant some didn't get the treatment they needed.

Two Wuhan residents told the BBC about the harrowing experience of trying to get care for their loved-ones in a city overwhelmed by sickness.

'Grandpa rest in peace' - Xiao Huang

Huang was raised by his grandparents after his parents passed away when he was a child.

All he ever wanted was to provide for his grandparents, both in their 80s, so that they could enjoy retirement in bliss, he says.

But in the space of just over a fortnight, his grandfather was killed by the coronavirus, and now his grandmother is in a critical condition.

Huang's grandparents started to have respiratory symptoms on 20 January. They couldn't go to a hospital until 26 January as it was difficult for them to get around after Wuhan was put into effective lockdown on 23 January, with public transport suspended.

They were diagnosed with the novel coronavirus on 29 January, but were only admitted to a hospital three days later.

But the hospital was so full that there were no empty beds. His grandparents had high fever and difficulty breathing, but were only offered seats in the corridor. He begged the hospital staff and he managed to get a long chair and a folding bed.

"There's no doctor or nurse in sight," Huang wrote in his diary, "Hospital without doctors is just like a graveyard."

The night before his grandfather passed away, Huang was with his grandparents in the corridor. He kept chatting with his grandmother so that she wouldn't know that his grandfather was experiencing delirium, he says.

A bed was finally available three hours before his grandfather died. Huang was by his bedside till the last minute.

He wrote on Weibo, China's Twitter-like platform: "Grandpa, please rest in peace. There's no pain in heaven."

"Many patients died without the company of family members and couldn't even get a last look at each other."

His grandmother is battling for her life in the hospital, and he spends as much time as possible with her.

"There's no effective medicine. Doctors told me not to hold out hope, and she can only get through by herself," he said.

"We can only let fate decide."

Since 7 February Xiao Huang has himself been feeling unwell and has now been quarantined for two weeks in a hotel.

'She started to cough blood' - Da Chun

In early January, Da Chun's mother developed a fever. The family was not particularly alarmed, thinking that it was just a cold. They had heard little about the mysterious disease that was quietly spreading in the city of 11 million.

But her fever did not subside for a week, even though she received injections from a community clinic. On 20 January, the same day when Chinese authorities admitted that the coronavirus is transmittable between humans, he brought his mother to an outpatient clinic designated for people with fever.

After looking at the chest scan and results of the blood test, the doctor told them that his mother had been infected with the novel coronavirus.

"Till this day, I am still in disbelief," says Da Chun.

But more bad news came. The doctor said his mother, 53, could not be admitted to a hospital because they didn't have the test kits to confirm the diagnosis. The test kits were only available at eight designated hospitals in late January.

"A doctor of a designated hospital told me they don't have the right to hospitalise my mum. It's the local health commission that allocates beds for confirmed cases," the 22-year-old says. "So, doctors can't do [the] coronavirus test to confirm my mom as [an] infected case, and can't offer her a bed."

Da Chun says his mother was not an isolated case. In a chat group with more than 200 members on the popular messaging app WeChat for families of infected patients people shared similar stories.

His brother would queue up at hospitals to check if there were beds available. He would go to the clinic with his mother so that she could get drips. But during these visits, they saw patients pass away inside observation rooms before getting tested or admitted.

"The dead bodies were wrapped and taken away by parlour staff," he says. "I don't know if they will be counted as deaths [caused by the novel coronavirus]."

His mother's condition continued to worsen. She started to cough blood, and there was blood in her urine.

On 29 January, his mother was finally admitted to a hospital, but he says she received no treatment and the hospital did not have sufficient equipment during the first days when she was first hospitalised.

But he's not giving up hope that his mother will recover.

Reporting by the BBC's Joyce Liu and Grace Tsoi. Illustrations by Gerry Fletcher.

(Both Da Chun and Huang used their social media aliases when speaking to the BBC)

Read more about the coronavirus and its impact

SHOULD WE WORRY? Our health correspondent explains

YOUR QUESTIONS: Can you get it more than once?

WHAT YOU CAN DO: Do masks really help?

UNDERSTANDING THE SPREAD: A visual guide to the outbreak

LIFE UNDER LOCKDOWN: A Wuhan diary

ECONOMIC IMPACT: Why much of 'the world's factory' remains closed