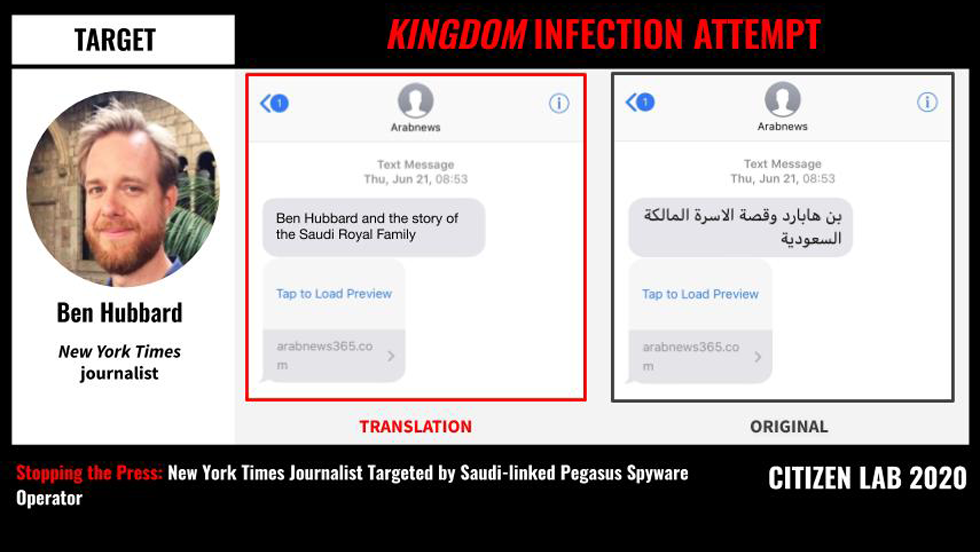

- New York Times journalist Ben Hubbard was targeted with NSO Group’s Pegasus spyware via a June 2018 SMS message promising details about “Ben Hubbard and the story of the Saudi Royal Family.”

- The SMS contained a hyperlink to a website used by a Pegasus operator that we call KINGDOM. We have linked KINGDOM to Saudi Arabia. In 2018, KINGDOM also targeted Saudi dissidents including Omar Abdulaziz, Ghanem al-Masarir1, and Yahya Assiri, as well as a staff member at Amnesty International.

- Hubbard is among a growing group of journalists targeted with Pegasus spyware. As part of our continued investigation into threats against journalists, Citizen Lab also identified evidence suggesting a Pegasus operator may have been infecting targets while impersonating the Washington Post in the weeks leading up to and after Khashoggi’s killing in 2018. There is no overlap between this activity and reported events surrounding the mobile phone of Jeff Bezos.

Pegasus is the name of a mobile phone spyware product made by NSO Group, an Israeli-based company that develops and sells surveillance technology.2 Since 2016, researchers have documented the abuse of Pegasus against journalists, human rights defenders, and members of civil society. In one case, Pegasus was used to target the wife of a slain journalist in Mexico.

Several reports by Citizen Lab and Amnesty International in 2018 showed that a Saudi-linked Pegasus operator that we call KINGDOM was targeting dissidents and regime critics. On July 31, 2018, Amnesty International and Citizen Lab reported that an Amnesty International staffer, as well as a “Saudi activist based abroad” (later identified as London-based dissident Yahya Assiri) was targeted with Pegasus. On October 1, 2018, Citizen Lab reported that Canadian permanent resident and Saudi dissident Omar Abdulaziz was targeted with Pegasus. During the period when his phone was monitored, Abdulaziz was apparently in close contact with murdered Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashogghi.

On November 11, 2018, Forbes reported that Saudi dissident, Ghanem al-Masarir, was targeted with Pegasus. If the targets had clicked on the links in the text messages they received, the KINGDOM operator would have been able to closely monitor these individuals’ communications and plans. Abdulaziz filed a lawsuit against NSO Group in Israel, and al-Masarir filed a lawsuit against Saudi Arabia in the UK.

Ben Hubbard is the Beirut Bureau Chief of the New York Times. Prior to his promotion to that role, Hubbard reported on Saudi Arabia, including on Crown Prince Mohamed Bin Salman (MbS). In an announcement of his promotion, the New York Times noted that Hubbard had “turned out deeply revealing reports from a closed society that is changing rapidly under a headstrong crown prince,” and had “…peeled back the curtain from the prince’s relentless consolidation of power.”

2.1. Pegasus Infection Attempt

On June 21, 2018, Hubbard received an SMS on his phone stating in Arabic: “Ben Hubbard and the story of the Saudi Royal Family.” Hubbard provided this message to the Citizen Lab in October 2018 for analysis. With Hubbard’s consent, we are now able to report on this case.

The link sent to Hubbard led to the site arabnews365[.]com, and was sent from a sender that called themselves “Arabnews.” The full link is:

https://arabnews365[.]com/wqbgGdwlk

Hubbard recalls that he did not click on the link and we are not able to determine whether his phone was successfully infected.

2.2. Connection with Pegasus Infrastructure

At the time the SMS was sent to Hubbard, the arabnews365[.]com domain was active and belonged to the portion of NSO Group’s Pegasus infrastructure used by the KINGDOM operator. The domain was also independently identified by Amnesty International as belonging to NSO Group’s infrastructure. In a previous report, we provided a comprehensive technical description of how we identify and scan for Pegasus infrastructure. In this section, we briefly summarize this process.

In 2016, Citizen Lab published the Million Dollar Dissident report, the first public research to identify NSO Group’s Pegasus spyware. In Million Dollar Dissident, we reported on an attempted intrusion of United Arab Emirates (UAE) activist Ahmed Mansoor’s phone using a text message with a malicious link promising “New secrets about torture of Emiratis in state prisons.”

Our investigation included scanning the Internet to find Command & Control (C&C) servers that behaved similarly to the ones communicating with the spyware sent to Mansoor. While the Pegasus servers we found were pulled offline even before we published Million Dollar Dissident, we continued to monitor them in case some of them might come back online. In the weeks after our report, we noticed a small number of Pegasus servers that came back online, but the servers no longer matched our fingerprint. We built a new fingerprint based on this behaviour, and began conducting regular Internet scans to find servers matching this new fingerprint.

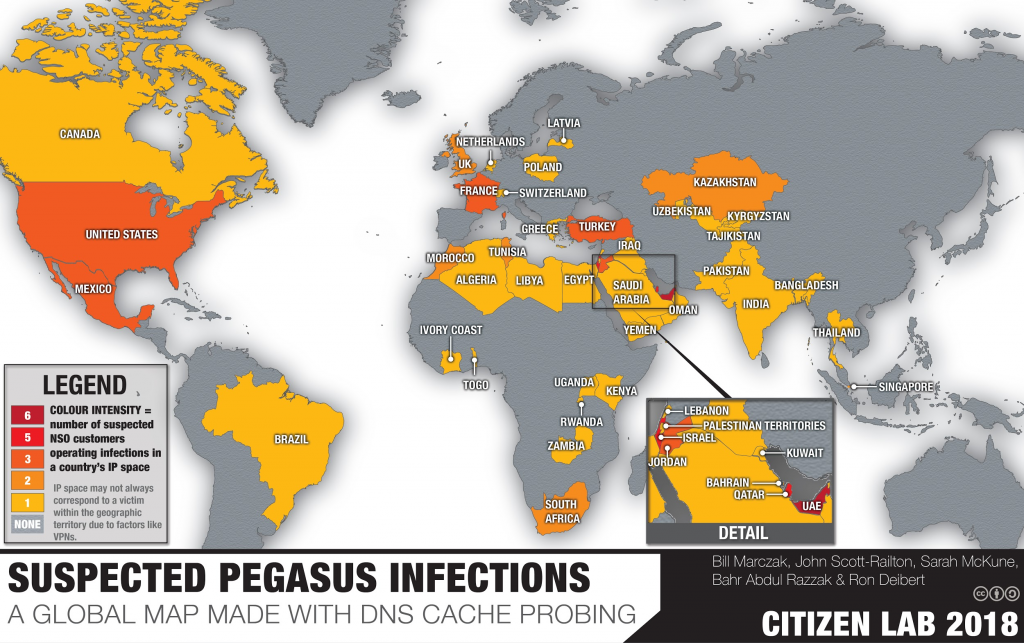

In September 2018, Citizen Lab published Hide and Seek: Tracking NSO Group’s Pegasus Spyware to Operations in 45 Countries, which described the results of this follow-up scanning, conducted between August 2016 and August 2018. In these scans, we detected 1,091 IP addresses and 1,041 domain names matching our new fingerprint. We further grouped these IPs and domains into 36 distinct Pegasus operators using a technique we developed and named Athena. We also devised a new way to conduct DNS Cache Probing, and used this method to find likely infections, by identifying Internet Service Providers (ISPs) where one or more user was repeatedly looking up domain names associated with Pegasus C&C servers.

As anti-democratic, authoritarian forces are on the rise in many countries, journalists are increasingly targets for surveillance and physical harm. Products like NSO Group’s Pegasus spyware provide government clients with a powerful tool to surreptitiously monitor journalists, their sources, and the stories on which they are reporting. Many of NSO Group’s clients appear to lack rigorous oversight over their security services, and have a track record of human rights abuses, including threats against journalists.

3.1. A Growing List of Journalists Targeted with Pegasus

Since 2016, investigations conducted by Citizen Lab and other researchers have now identified at least 13 journalists and civic media actors targeted with Pegasus spyware (Figure 4). In Mexico alone, we have documented at least nine journalists targeted with Pegasus. Azam Ahmed of The New York Times believes he may have received an infection attempt while working in Mexico, but the message was deleted before Citizen Lab was able to analyze it.

Troublingly, in both Mexico and Saudi Arabia, spyware infection attempts have been linked to or associated with targeted killings. For example, our report into Saudi surveillance of Omar Abdulaziz was published October 1, 2018. The following day, Jamal Khashoggi—Abdulaziz’s confidant with whom he had been communicating with for months—was executed. Similarly, two days after Mexican investigative journalist Javier Valdez Cárdenas was gunned down in a cartel-linked murder, his wife and colleagues received SMS messages designed to install Pegasus on their phones. These links between murders and attempts of targeted surveillance are echoed by recent investigative reporting in the Financial Times detailing targeting against the Rwandan diaspora, including opposition activists and other exiles threatened by Rwandan death squads.

3.2. An NSO Operator May Have Masqueraded as the Washington Post

Citizen Lab has also identified evidence suggesting that a Pegasus operator may have been masquerading as the Washington Post to infect targets in the weeks before and after the October 2018 killing of Jamal Khashoggi. While the timing overlaps with the killing, the two are not necessarily related. We have very recently shared some technical details with the Post’s information security team, and there are no indications that this targeting affected anyone at the Washington Post. We also note that there is no overlap between the timeline of this activity and recently reported events surrounding the mobile phone of Jeff Bezos.

3.3. Commercial Spyware Used to Hack Journalists

NSO Group’s Pegasus spyware is not the only commercial surveillance technology on the market, nor is commercial spyware the only means by which abusive surveillance of journalists can be carried out.

Prior Citizen Lab research has identified targeted espionage against Ethiopian journalists linked to the Ethiopian government, and using spyware sold by Hacking Team (now known as Memento Labs) and Cyberbit (an Israeli-based spyware vendor). Our Stealth Falcon report detailed a targeted digital espionage campaign against UK-based journalist Rori Donaghy using bespoke spyware linked in media reports to UAE-based cybersecurity firm Dark Matter. Likewise, our research has documented numerous cases of targeted digital espionage against journalists and news organizations covering Russia, Tibet, and China, dating back to 2009.

Academic research on journalist security show that journalists do not share the same digital security practices and perceptions across the profession. For example, a study found that a common mindset for journalists is to only prioritise digital security if they perceive the stories they are working on as sensitive enough to attract the attention of government authorities.

Echoing these findings, ongoing research by the Citizen Lab finds that investigative reporters tend to take digital security more seriously than their peers who work on non-investigative beats, and have higher familiarity with digital security tools and practices.

As an investigative reporter covering a sensitive topic, Ben Hubbard was wary of suspicious messages and chose to share the one he received with us for analysis. Yet, not all targeted journalists are working on a topic where the risk of surveillance may be so obvious.

Some studies show that differences in education and training, alongside other variables such as financial incentives and institutional culture, may play a key role in closing or compounding gaps in digital security practices. For example, a peer-reviewed study that interviewed journalists in the US and France found journalists, editors, and technical staff may conceptualise and prioritise security issues differently, to the effect that reporters may resist and resent top down efforts to change security practices, or may see security as important, but struggle to get institutional support towards its implementation. Another such study involving US-based journalists found a general lack of security culture in journalism and conflict between journalists and IT professionals within news organisations as among the key barriers to journalists adopting secure tools and practices.

The Citizen Lab recently conducted a survey of 124 journalism schools across the US and Canada to probe what digital security courses they offered. Only half of the schools surveyed offered some form of digital security training, and only a quarter required it. Among programs that offered training, the majority devoted less than two hours to the subject.

Taken together, this body of research shows that more action is needed to prepare journalists for the digital threats they face. We believe that reports—such as this one—that continue to expose real cases of digital threats faced by journalists may help motivate those agitating for more methodical attention to digital security in journalism schools and news organizations.

The targeting of yet another journalist—in this case at the New York Times—makes it clear that the current regulatory regime for the spyware industry is not working. Absent strong regulation and control, the industry will continue to bolster authoritarianism by helping powerful elites invisibly thwart the work of journalists seeking to hold them to account.

In 2019, the UN Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression concluded that existing legal frameworks are insufficient, and called for a moratorium on the export, sale, transfer, use, or servicing of privately developed surveillance tools until a human rights-compliant safeguards regime is in place.

Unfortunately, states have not acted—leading victims to take accountability into their own hands. In 2019 alone, several lawsuits were filed against spyware companies and their government clients, with plaintiffs including spyware targets, a human rights organization, and a major tech company. While these lawsuits may be the best option in the short-term, this piecemeal approach cannot provide the same benefits as comprehensive regulation of the industry. Until there is action on this front, the media and other institutions that protect us all are vulnerable like never before.

We thank Ben Hubbard for sharing his suspicious message with us, along with the many other journalists who have participated in our previous investigations. Special thanks to Sharly Chan, Miles Kenyon, and Adam Senft for copy editing and additional assistance.

All research involving human subjects conducted at the Citizen Lab is governed under research ethics protocols reviewed and approved by the University of Toronto’s Research Ethics Board. The Citizen Lab does not take general or unsolicited inquiries related to individual concerns regarding information security and cannot provide individual assistance with security concerns.

1. Also sometimes referred to in media reporting as Ghanem al-Dossari.

2. NSO Group also sometimes goes by the name Q Cyber Technologies, and Pegasus also appears to be sold under various names such as “Q Suite.”