A meteorite that crashed into Australia back in 1969 contains stardust dating back some 7 billion years, predating the formation of Earth by 2.5 billion years. The remarkable discovery offers a snapshot of the conditions that existed long before our solar system came into existence.

Ancient grains found inside the Murchison meteorite have been dated to between 5 billion and 7 billion years old, according to new research published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The new paper was led by astronomer Philipp Heck from the University of Chicago.

These grains originated as interstellar dust, and they’re now considered to be the oldest known solid materials on Earth, which formed around 4.5 billion years ago. It’s a remarkable finding, as these materials are evidence of the conditions that existed prior to the formation of our solar system. And indeed, these grains are already providing new astronomical information, including evidence of a “baby boom” period of star formation that happened several billion years ago.

“This is one of the most exciting studies I’ve worked on,” said Heck in a press release.

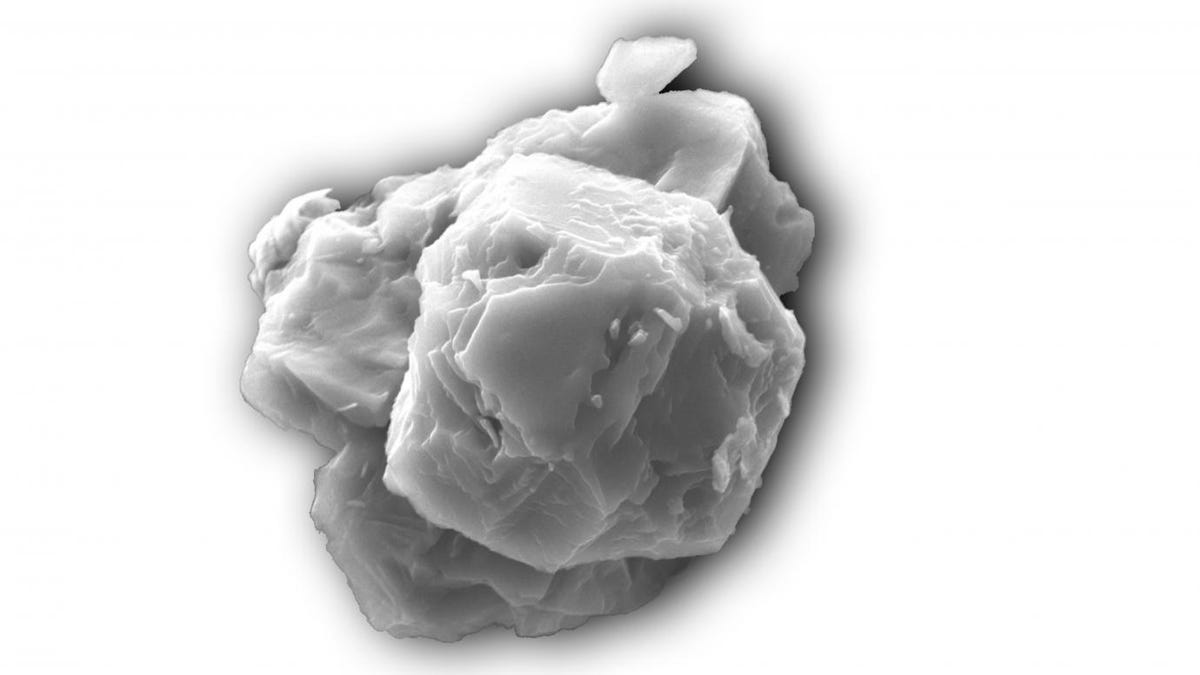

Stardust comes from stars (shocking, I know) and is hurled into space by stellar winds. Eventually, these bits of stellar matter re-accumulate, forming yet more stars, and sometimes planets, moons, and meteorites (fun fact: you’re also made from this stuff). On Earth, traces of these grains are scant, appearing in only 5 percent of meteorites. They’re also very tiny. As a University of Chicago press release notes, “a hundred of the biggest ones would fit on the period at the end of this sentence.” More specifically, they’re about 8 microns across, which is roughly the size of a single red blood cell.

David Bekaert, a researcher at the Center for Petrographic and Geochemical Research (CPRG) in Nancy, France, who wasn’t involved with the new study, said interstellar dust particles that predate our Sun are known as “presolar grains,” a portion of which reached rocky bodies that arose during the formation of our solar system.

“We’ve known their existence in primitive meteorites for a long time,” Bekaert told Gizmodo. “However, assessing how old they are, and whether or not they were generated in a single star formation episode that predated the formation of our own solar system, had remained hampered by the lack of reliable techniques to date individual presolar grains.”

Key to the new study was an abundance of presolar grains packed inside the Murchison meteorite and a new strategy to date them. But the first step was to isolate the grains.

“It starts with crushing fragments of the meteorite down into a powder,” Jennika Greer, a co-author of the study and a graduate student at the Field Museum and the University of Chicago, said in the press release. “Once all the pieces are segregated, it’s a kind of paste, and it has a pungent characteristic—it smells like rotten peanut butter.”

This putrid-smelling stuff was then dissolved with acid, leaving a few dozen of these presolar grains behind. To date these isolated grains, the researchers applied a technique that measured the degree to which the grains were bombarded by cosmic rays—high-energy particles that zip through space and can penetrate solid objects. Because prolonged exposure to cosmic rays results in heavier elements, the researchers took note of the quantity of these easily detectable elements found in the grains to infer their relative age.

Results showed that the presolar grains were quite ancient, having absorbed a tremendous amount of cosmic rays over the eons. The oldest grains were dated to about 7 billion years ago, with the majority dating to between 4.6 billion and 4.9 billion years ago and a small handful dating to 5.6 billion years ago. So all the interstellar particles found in the Murchison meteorite originated before the formation of our solar system and Sun.

Interestingly, this result shows that star formation was not constant in the galaxy. The glut of particles dating to 4.6 million-4.9 billion years ago suggests these grains originated during a time of intense stellar formation—a kind of baby boom for stars in the Milky Way (our galaxy formed around 8 billion years ago). And in fact, Heck said it was “one of the key findings of our study.”

Bekaert agreed, saying the new paper “relates an impressive technical achievement, as well as an important scientific discovery, providing us with new insights into the evolution of matter within our galactic neighborhood,” up to around 7 billion years ago, he told Gizmodo.

With this new technique, astronomers would be wise to re-visit similar meteorites containing presolar grains to corroborate these findings. There’s still plenty of history to be found in these primordial objects.