In astronomy, an aurora is a luminous phenomenon that consists of streamers, arcs, or ripples of dancing vibrant light that appear in the upper atmosphere of a planet's magnetic polar regions. Auroras on planet Earth have been found to be caused by energetically charged particles that travel from the sun to the Earth on solar wind, and are then magnetically drawn to the poles. Once there, they begin to collide and interact with gaseous atoms and molecules, and visible energy is released in the collisions, which gives observers an aural light show. Auroras in the northern hemisphere are known as aurora borealis, or northern lights; in the southern hemisphere, they are called aurora australis, or southern lights.

In Latin, aurora means "dawn," and in Roman mythology, Aurora is the personification of dawn. (The Greek counterpart is Eos, whose name also means "dawn.") In Late Latin, borealis means "of the north," so aurora borealis literally translates as "dawn of the north." Its polar opposite, australis, means "of the south," giving rise to the name aurora australis, "dawn of the south." Both phenomenon are similar in their dazzling light shows made up of colors interacting in various forms, including vibrant rippling curtains, waving arcs, shimmering bands, and shooting rays. The colors of the lights—which range from red, blue, and purple to green and yellow—depend on which gaseous molecules (mainly oxygen or nitrogen) collide with the solar particles as well as at what altitude that interaction takes place.

The aurorae are generated by the solar wind—a stream of charged particles travelling from the outer layer of the sun, or corona, and slamming into Earth's magnetic field. This acts like a shield around the planet that deflects most of the particles. But at its weakest points around the poles, some can penetrate into the upper atmosphere, where they collide with and excite gas molecules. As these molecules de-excite, they release the photons of light that make the aurorae. The type of excited molecule, along with the altitude of the collisions, determine the colour of the aurorae.

— Abigail Beall, The New Scientist, 7 Dec. 2019

A rainbow is an arc or circle that exhibits, in concentric bands, the colors of the spectrum and that is formed opposite the sun by the prismatic refraction and reflection of its rays in raindrops, spray, or mist. The appearance of a rainbow depends on the angle at which the sun's rays are refracted (that is, bent) and reflected within the drops of water suspended in the atmosphere. Since white sunlight is composed of all the colors of the spectrum, with the right refraction and reflection in the ideal sized drops, it can be separated into the different colors that form a rainbow—those being, from outside to inside, red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, and violet. A less distinct double rainbow may also appear; its colors are reflected in reverse order of the primary rainbow. The name rainbow originates in Old English and is cognate with older Germanic compounds formed from base words meaning "rain" and "bow."

A fogbow's formation is similar to the rainbow's except that sunlight interacts with particles of water suspended in thin fog, especially over bodies of water or in mountain valleys. The water droplets in fog are finer than the raindrops that form rainbows, and the smaller passage for light inhibits prismatic refraction within them. Instead the light undergoes diffraction in foggy conditions, which means most of its rays, rather than breaking up into distinct colors as they pass through the drops, bend around the drops and scatter, producing a whitish band with very little or no color.

Whereas water droplets act like small prisms, producing all the colours of the rainbow, the fog droplets—which can be hundreds of times smaller—process light in a different way. The main difference is the diffraction the fog causes, where the light is scattered more than it's reflected, leaving only the brightest parts of the pattern: the white fog bow.

— David Nield, Sciencealert.com, 24 Nov. 2016

Two other celestial "bows" are the sunbow and moonbow. A sunbow is formed similarly to that of a rainbow by sunlight shining through vapor or mist; a moonbow (a.k.a. "the moon rainbow") is also similarly formed but by sunlight reflected off the moon. The names of both first appear in 19th-century English writing, as does fogbow.

Like Peter Pan, the ice clouds have no shadow; and the sun and moon shine through them with little difficulty. However, there will always be a sun or moon halo present, often colored swatches of cloud called "sunbow" and "moonbow." If the sun is shining through two layers of ice cloud, there will be two halos.

— Eric Solane's Weather Book, 1949

The word halo first brings to mind, to many people, the image or a radiant circle or disk surrounding or topping the head of a holy person as a representation of spiritual character. However, halo—a borrowing of the Greek word meaning "threshing floor," "disk of the sun or the moon," or "halo around the sun or moon"—first comes to light in 16th-century English as an astronomical word for a circle of light appearing to surround the sun or moon, resulting from refraction or reflection—or both—of sunlight or moonlight in ice particles suspended in the atmosphere.

A Sun halo is caused by the refraction, reflection, and dispersion of light through ice particles suspended within thin, wispy, high altitude cirrus or cirrostratus clouds. As light passes through these hexagon-shaped ice crystals, it is bent at a 22° angle, creating a circular halo around the Sun. The prism effect of light passing through these six-sided ice crystals also separates the light into its various color frequencies, making the halo look like a very pale rainbow, with red on the inside and blue on the outside.

— The Farmers' Almanac, 2019

It is in the 17th-century that the sacred halo, synonymous with nimbus, comes to be.

In Middle English, aureole was declared a word for a heavenly crown worn by saints; a sense still in use today in religious and historical contexts. It is also used figuratively in literature—for example, an author might write of "an aureole of golden blonde hair" or "an aureole of youthful spirit." The word derives from Medieval Latin aureola, which was formed from Latin aureolus, meaning "golden."

In the 19th century, astronomers transferred the "halo" sense of the word to the luminous area surrounding the sun or other bright celestial bodies when seen through thin cloud, fog, or mist. Basically, an aureole appears when light shines through a mass containing droplets of water, and in this sense, its name is synonymous with corona and glory.

Last week, when I looked at the first image ever made of a black hole—erroneously called a “photograph,” it is in fact a digital composition stitched together from the observations of eight telescopes—I could hardly make it out. The supermassive void at the heart of the Messier 87 galaxy is about as large as our solar system.... What the picture shows is the event horizon that surrounds it, an aureole of blazing fire; but the halo appears blurry and indistinct, and within seconds it had been repurposed for all manner of pathetic digital jokes. Try to capture the infinitude of space and this is what you get: a fall from grace, a descent from the heavens to earth.

— Jason Farago, The New York Times, 18 Apr. 2019

In Latin, corōna was the name for a garland worn on the head as a mark of honor or emblem of majesty as well as for the top part of an entablature or a halo around a celestial body. The word was originally borrowed into English in the 16th century for an entabulature's, or cornice's, topper. Astronomers then employed corona as the name for the outermost layer of the sun's atmosphere, which is hidden by the brightness of the sun itself but is visible to the unaided eye during a total solar eclipse, when the sun is completely obscured by the moon. During the eclipse, the sun's corona appears as a halo, or glory, of light surrounding the moon.

During a total solar eclipse, when the sun is obscured by the moon's shadow, the dark disc is seen to be surrounded by a "glory," of fringe of radiant light, which is called the corona.

— Thomas Henry Huxley, Physiography, 1877

A sun dog is any of several bright spots, mostly whitish but often tinged with an orange or red color, that are formed when sunlight refracts through ice crystals in clouds and that appear on the parhelic circle on either side of the sun. The sun dog's closeness and resemblance to the sun led to its nickname mock sun.

A parhelic circle is a luminous circle or halo that appears parallel to the horizon at the same altitude of the sun. Parhelic is the adjectival form of parhelion, a synonym of sun dog risen from Greek parēlion. That Greek word combines the prefix para- ("beside") and hēlios ("sun"); literally, it means "beside the sun."

Given its ancient Greekness, one might guess that parhelion is the older of the two synonyms; however, it entered English much later than one might expect, and only decades before the dawn of sun dog. Parhelion awakens in English writing in the late 16th century, whereas sun dog begins shining during the first half of the next.

Sun dogs are known as parhelion, halos, or "mock suns." They are optical effects caused by the refraction of sunlight by ice crystals in the atmosphere, which results in what can appear to be two rainbows on either side of the sun.

— Robyn Wilkinson, Caledon Enterprise, 21 Jan. 2019

Why is dog used in sun dog? We don't know, and we also don't know the exact origin of the canine sense. If you find the home of this dog, please contact us.

Moon dog is a colloquial synonym of the lofty paraselene. Both words refer to a luminous appearance, or bright spot, that is seen in connection with lunar halos caused by the refraction of moonlight through ice crystals in the atmosphere. The prefix para- of paraselene means "closely related to," and its base is the Greek word meaning "moon," selēnē. Paraselene begins to shine in English writing about mid-17th century. The nickname moon dog appears in the 19th.

One of the most singular phenomena, caused by the refractive agency of the atmosphere upon the lunar rays, occurred last evening that we have ever witnessed. We certainly never saw the like. The moon was surrounded with a halo of immense diameter, while at opposite points of the ring, situated relatively on the plane of the horizon, were two auroral offshoots of light, called we believe, in common language, moon dogs.

— The Buffalo (New York) Commercial Advertiser, 17 Dec. 1850

Before moon dog, a paraselene was called a mock moon.

We omitted last week to notice the rare phenomena in the heavens on Saturday evening previous to our publication day. As the moon ascended the horizon in the East, she was accompanied by two moon dogs, or mock moons, one on each side, of almost equal brilliancy with old Luna herself.

— The Belvidere (Illinois) Standard, 8 Jan. 1861

Albedo refers to the fraction of light or radiation that is reflected by a surface or body. The word, which is from Latin albus, meaning "white," is applied in astronomy to describe the reflective properties of planets, natural satellites, and asteroids. To determine the brightness of such objects, the albedo, diameter, and distance are taken into account.

You don't need to be in an observatory to estimate the albedo of a surface. For example: a covering of fresh white snow glistens in the sun like a mirror reflects light, and one can surmise that the sun's rays are being reflected back into the atmosphere. Judging by the snow's brightness, a large percent of them are probably being reflected back, which means that most of the radiation is being reflected and only a small percentage is being absorbed; therefore, the snow has a high albedo. Black asphalt, on the other, is less reflective and absorbs more of the sun's radiation, making that dark surface with a low albedo blistering hot in the sun. Similarly, a white shirt has a higher albedo than a dark one because darker colors are less reflective and more absorbent of the sun's radiation. That's why you're hot in that black shirt on a bright summer's day—its albedo is low.

First off, an effect called "albedo" refers to the whiteness of snow covered land and ice reflecting heat back into space. Albedo is a measure of reflexiveness of heat off the surface of water and land, a big factor in winter sliding into spring. Snow on tundra and ice reflect and toss the heat of the sun back into space. Dark forests and dark open water absorb heat.

— Sandra L. Medearis, The Nome (Alaska) Nugget, 22 Mar. 2019

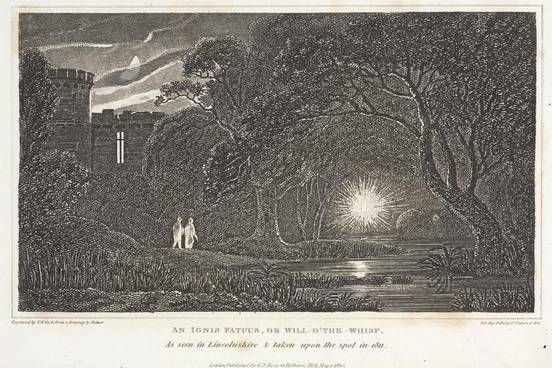

Ignis fatuus is a Latin term meaning, literally, "foolish fire." In English, it has come to designate a hovering or flitting light that sometimes appears in the night over marshy ground that is attributable to the combustion of gas from decomposed organic matter. Other names for this light are jack-o'-lantern and will-o'-the-wisp—both of which are connected to folklore about mysterious men, Jack and Will, who carry a lantern or a wisp of light at night. A Scottish name for ignis fatuus is spunkie, from spunk, meaning "spark" or "a small fire." It has also been told that ignes fatui (the Latin plural form) are roaming souls. No doubt these stories spooked listeners by candlelight, but in time, advancements in science not only gave us electricity to dispel the darkness but proved ignis fatuus to be a visible exhalation of gas from the ground, which is rarely seen today.

But thou art altogether given over, / and wert indeed, but for the light in thy face, the son of utter / darkness. When thou ran'st up Gadshill in the night to catch my / horse, if I did not think thou hadst been an ignis fatuus or a / ball of wildfire, there's no purchase in money. O, thou art a / perpetual triumph, an everlasting bonfire-light!

— William Shakespeare, Henry IV, Part 1, ca. 1597

A light pillar is a white halo that extends vertically above and below the sun or moon and is caused by reflection from the upper and under surfaces of ice crystals. Light pillars are not only caused by the reflection of natural sunlight and moonlight off of ice crystals but by the reflection from artificial city lights, and in the latter case they appear as ascending beams of light in the color of their source.

The ice fog has also created mesmerizing sundogs and light pillars. The latter describes a phenomenon in which a vertical beam—or pillar—of light seems to extend above or below a light source. We witnessed scores of nocturnal light pillars in midtown Anchorage the night of Jan. 4,... all of those pillars emanating upward from artificial lights. Jan later did some online research, which explained that the narrow, vertical beams are created by the reflection of light from the dense multitudes of crystals suspended in the ice fog. Each of us (at different times) later witnessed a solar pillar, formed by the reflective action of those ice fog crystals on the low-angled light of the setting sun.

— Bill Sherwonit, The Anchorage (Alaska) Press, 10 Jan. 2019

Lightning and lightening are related words that both strike English in the 14th century. The bolt in lightning bolt and thunderbolt is from an Old English word related to Old High German bolz, meaning "crossbow arrow," and, perhaps, Lithuanian beldėti, "to knock or beat." You might also be familiar with the collocation "a stroke of lightning." Both bolt and stroke, in reference to lightning, light up in the English language during the 1500s, along with flash, as in "flash of lightning," which is believed to be of onomatopoeic origin.

The experiment proposed by Mr. Franklin, to prove that lightning and the electrical fire are the same, has often been repeated with success both in England and abroad; so that the most noted electrical experiments have been performed by fire drawn from the clouds.

— Ebenezer McFait, "Observations on Thunder and Electricity" in Essays and Observations, Physical and Literary, 1754

The word lightning itself refers to a brief but intense luminous phenomenon that is caused by an electrical discharge within clouds, between clouds, between clouds an air, or from clouds to ground.