I’ll start with this question: has 2019 been a good year for poetry? And, if it has, why do you think so?

From my perspective, every year is a good year for poetry. There’s rarely a bad year; people are writing good poems all the time. I teach some poetry every year; most of what’s on my repertoire is not brand new. In my former job as curator for the Poetry Project of St Mark’s Church, I would see around a hundred poets a year. Since that is no longer my job, it’s harder for me to come into daily contact with brand new work, so I rely on my existing network, which has built up through many years of affiliation through curating and writing. One of the things that I do is rely on other people to tell me what to read, which I did in this case as well.

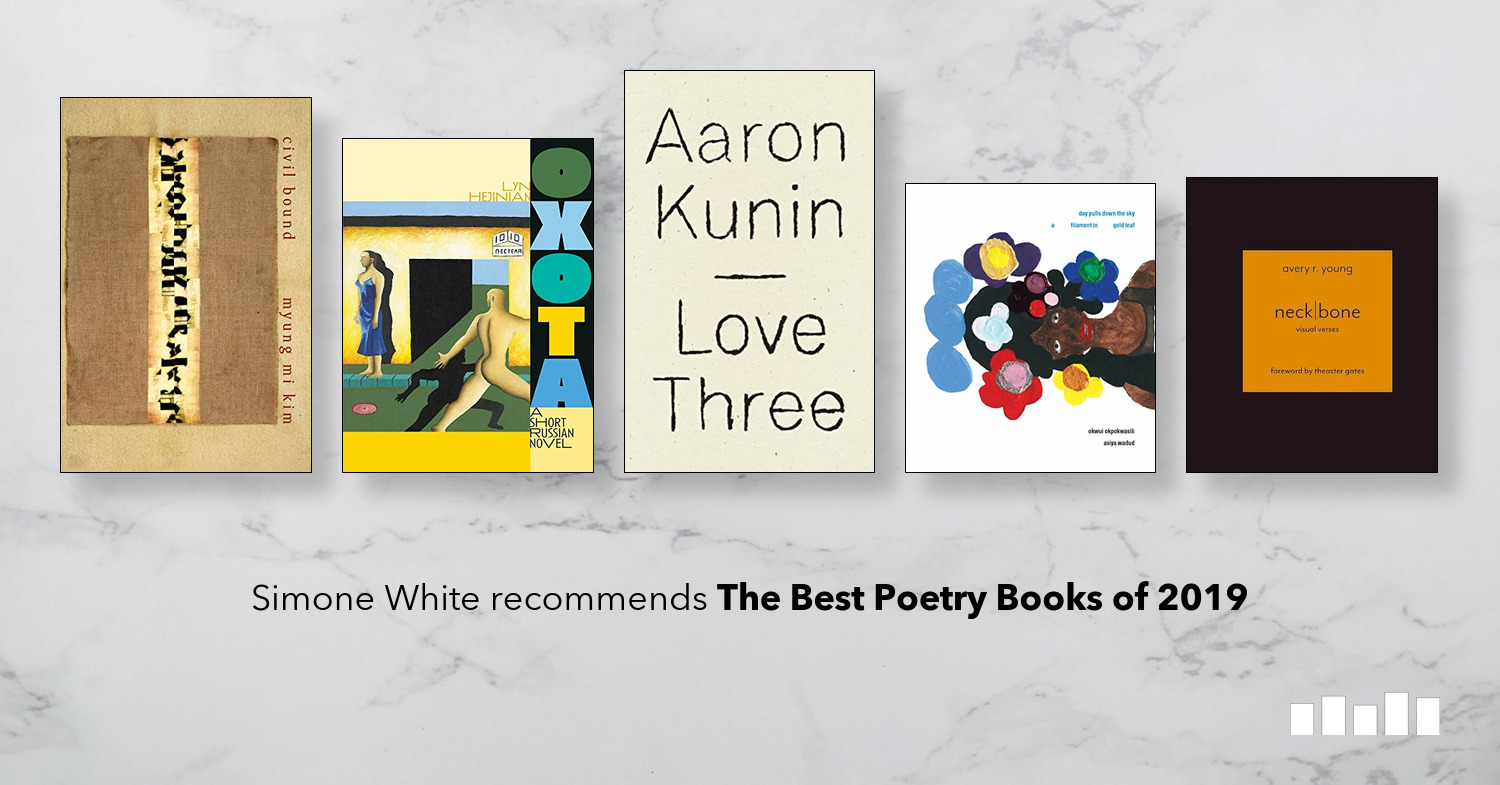

I’m sure everyone that reads this will be relying on you to tell them what to read as well! Do you want to talk about your first choice, Civil Bound by Myung Mi Kim? Can you tell us about Kim, what this book is about, and why you chose it?

Myung Mi Kim is a celebrated and established American poet who has been known to us since the late 1980s. She’s among my favorite poets. I teach her to my students, and I think about her work all the time. She’s one of the co-directors of the poetics program at SUNY Buffalo, which one of the only PhD programs in poetics in the United States. So she’s also an important mentor and teacher.

This is a new book. It just became available in October, and I was lucky to see an early iteration. What can I say? It is incredibly powerful and also very sparse—it has very few words. When I teach it to my students, who are undergraduates at the University of Pennsylvania, they open it and say, ‘There are almost no words in this book!’ We try to work together to understand how the poems become so powerful in spite of the fact of their obvious minimalism. It’s never clear how this operation works: how it is that a poet is able to achieve this effect of power with a very spare style? But that’s this book’s immediate and first characteristic.

“It’s not actually a puzzle at all; it’s a reorientation of literacy”

What’s it about? I think this book is very much about something. It’s about people moving around the globe, and the ways in which people have been moved around the globe. It ties together a bunch of different documents of the settlement of the American West, including documents of the US government’s development of the Panama Canal. The poems appear sometimes on the page as small phrases or sentences from these actual historical materials. In other instances, they’re arranged in completely new forms by Myung Mi Kim—including a form that looks very much like a crossword puzzle or a word search puzzle. But what’s actually happening is you’re being asked to read from top to bottom instead of left to right. So it’s not actually a puzzle at all; it’s a reorientation of literacy. Myung is Korean-American, so this is also a gesture towards other kinds of graphicity.

We’re also being asked to consider the accumulation or dissemination of various kinds of literacies through global kinds of movement. At the very beginning of this book, a snarling dog comes up out of the ocean, and it seems to me that what she manages to achieve in this book is a symphony of different voices that are speaking about the ways in which the postmodern world has been built.

There’s also this incredible line, which occurs right smack in the middle of the book on a page all by itself: “If a species cannot find a sonic niche of its own, it will not survive.” It’s a line that really ties together the book’s humanity—its interest in talking to all of us about what it means to live in a world in which people have been torn from their homes, or have voluntarily moved away from their homes and are trying to make new places to live.

It’s interesting to me that the strategies of formal inventiveness that you mention are meant to intervene in the reading process, and get the reader to encounter a poem differently or even renegotiate their definition of reading itself, moving them to an empathic experience they might not have otherwise had.

I think the limited number of words on the page—because it requires us to move so slowly through the thinking that’s happening in the book—also slows down our hardened expectations about the difficulty of moving through a world in this way. Part of being post-postmodern is our expectation around speed and density. She eliminates the possibility of dwelling or presuming that those things are the fundamental requisites of our experience.

Let’s move on to Lyn Hejinian’s new book Oxata: A Short Novel. For those of our readers who might not have prior knowledge of Hejinian or who wouldn’t know what the designation ‘Language’ poetry meant, I wonder if you could introduce first her, and then talk about why you chose Oxata.

Hejinian has been based for many years on the West coast, teaching at the University of California, Berkeley—another important institution for the study of poetry and poetics. She’s one of the most important figures in a movement we call ‘Language’ poetry, which is a concentration of writers and writing that began to take place in the late 1970s and took off in the early 1980s. She’s probably best known for her book My Life (1980), which is now canonical. It’s a kind of anti-autobiography written in prose lines: each section consists of 37 sentences, the age she was when the book was initially written. The book has continued to be written; there’s an updated version called My Life in the Nineties (2013).

Get the weekly Five Books newsletter

Lyn is considered not only one of the foremost practitioners of Language writing, but also one of its primary theoreticians. She’s also written essays about what Language poetry is, what its primary features are, including a very famous essay called ‘The Rejection of Closure,’ which I teach to undergraduates. If one of the primary questions about late twentieth-century US poetry is ‘Why is this poetry?’, it’s because it is never really clear that prose and verse are distinct from one another in Language poetry, insofar as its primary reflection is on the language itself, not on any prearranged or pre-perceived forms of verse or meter. It makes its own way primarily by virtue of the sentence.

Oxata: A Short Novel is an old book which has been reissued. This book is conceived in 270 ‘chapters’ of 14 lines each, and thinks about the experiences that Lyn had while she was a frequent visitor to Soviet Russia between 1983 and 1981. (These are all facts you can find out on the book’s jacket.) She’s been one of the primary translators of the Russian poet Arkadii Dragomoschenko. I remember seeing it and thinking, ‘What is this?!’ And my friend, another poet, Benjamin Krusling, said, ‘Oh, Wesleyan has just brought out Lyn Hejinian’s Oxata.’ And it had come to me in the mail, but I hadn’t opened it! So it was a happy accident that it was revealed to me in this way.

“Hejinian’s work has so much verbal energy; it’s as if there’s an unending supply of words and thinking”

What’s so incredible about Hejinian’s writing is that she never seems to run out of energy. One of the things that formal devices do for us, it seems to me, is allow us to fill in the lacks of our own imagination. All of us have lacks or blanks where we don’t have anything to do or say, and so as a poet you work in conversation with this formal device which gives you something to say; it is an engine of its very own. It has always seemed to me that Lyn doesn’t need that. Her work has so much verbal energy; it’s as if there’s an unending supply of words and thinking.

And yet she returns frequently to these formal devices, most recently in The Unfollowing (2016), which she calls an ‘anti-sonnet’ book. It’s fascinating that she’s returned to the sonnet form after Oxata, which was published in 1991—these 14 lines obviously mean something to her. And what do they mean?

There are many important and interesting things to note about this book, but one of them is that it’s a record of a time that none of us will ever be able to return to—pre-breakup Soviet Union. That world was gone by the time I was an adult. It’s a record of a kind of cross-cultural experience—the experience of going behind the Iron Curtain—that’ll never happen again. In a way, the book remains mysterious to me, not only because of that but also because it’s a document of Eurocentrism that I think is also no longer possible, where the object of fascination is what’s going on behind the Iron Curtain.

When I think of the contemporary poetry collections that have been recommended on Five Books in the last couple of years, it’s often a very immediate political consciousness: poems reflecting, whether explicitly or more obliquely, on the phenomenon of Trump, on Brexit, on borders. And now this book, whose historical consciousness is now very much of the past, has been reissued.

I suppose what you’re saying is that this represents a political consciousness that is nostalgic. That’s interesting. Her writing is so beautiful, in a way I just don’t know what to say about it. Maybe you’re right—maybe it’s not possible to write such a book now, because of pressing domestic and political concerns in the United States. Although maybe there is no such thing as a ‘domestic’ political concern.

But I want to show you this page of chapter 109, which is incredibly delightful. When I said it was fourteen lines—you would look at this page and ask ‘How is this 14 lines?’ There must be over 400 words here. And this is one of the sentences:

And so in a truly magical manner it has come about in apparently one continuous morning that I have become, he said, the possessor of multitudes of wide open windows and of sunlight tumbling into other minute fissures of an almost invisible brightness—why not see in this a special meaning

That one line actually takes up four lines of text on the page. Like all the books I’ve chosen, it makes me think about what it is that poetry’s trying to achieve inside its own world. Obviously poetry is bigger than any small conception of it could ever be, but Lyn’s capacity to explore all the possibilities of poetic writing astounds me. What is poetic writing? Not necessarily poetry, but what can we do when we set out to do something that has poetry as its center? She’s just continually surprising in this way.

The energy of that line you just read is amazing—I can see exactly what you mean; it just goes on and on. Do you want to talk next about Aaron Kunin’s Love Three?

Aaron Kunin is based in Los Angeles, California. When I was curating at The Poetry Project, his was one of the guest readings I was most surprised and delighted by. You never know what you’re going to get when someone goes to read their own work, but his was one of the most incredible performances of poetry I’ve ever seen. It wasn’t ostentatious, or a performance that looked like acting. It was a performance that tried to embody the physical experience of taking works from inside you and putting them outside you, using very powerful and exaggerated intakes of breath, long pauses, real physical stillness. It was an incredible reading, and he’s a terrific writer.

This book came to me in the mail from Aaron himself. When I opened it today to talk to you about it, I realized he’d written me a little note. I mention that because this is really how poetry circulates: sometimes people send you their books and they turn out to be wonderful! I know that Aaron Kunun is a great writer, but this book is really impressive. It was published by Wave Books, who’ve published some pretty significant titles, including Tyehimba Jess’s Olio (2016), which won the Pulitzer Prize, as well as Dorothy Lasky and Anselm Berrigan.

This is a fat, funny-looking book. It looks a little bit like a romance novel in terms of its size, thick and 5 x 7. It doesn’t look like an ordinary poetry book, and it’s not. Before you even get to the title page, it says:

This book is a few different things: a study of George Herbert’s seventeenth-century devotional poem ‘Love’, an essay on eroticizing power, and a memory palace of sexual experiences, fantasies, preferences and limits with Herbert’s poem as the key. Each numbered section is a restatement of Herbert’s poem. First, I paraphrase the poem, then I try to see what my paraphrase missed, then I study what other critics have written, and finally, I wrote about the poem through my sexual history. I try to avoid references to outside sources. Interested readers will find a complete bibliography and notes with page citations at the end of the book. This book is for Michael Clune.

That reminds me of Anne Carson’s Nox (2009).

Yes! There are a bunch of examples of these kind of quasi-scholarly books in poetry circles. Sometimes people call them ‘autotheory’, which just sounds crazy to me. I don’t know what they’re trying to say with that label. But some examples might be Nox, Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts (2015) or Bluets (2009), Maureen McLane’s My Poets (2012); Susan Howe’s My Emily Dickinson (1985) is an early example of this. Love Three is definitely in this tradition.

What distinguishes this book from others that might look like it (in terms of genre, or anti-genre) is how very strange some of it is. ‘Strange’ to me is a term of deep admiration. It makes me laugh; it’s charming; it’s so very careful in its examination of this George Herbert poem, which is printed at the beginning and is only 18 lines. And the book itself is 322 pages. But in spite of that length, it’s bound by its own particular conceit. This is three kinds of examination, he says: scholarly, personal, and literary critical, or close reading. But there are all kinds of possibilities. It’s as if he could have gone on forever on this subject. The expansiveness of that imagination, the way in which a very careful critical mind is at work here, greatly interests me.

I’ll read you a couple of the book’s phrases. The first line of section 41 is “Love humiliates me by making me act like a slob.” That’s a paraphrase of Herbert’s poem, apparently—but what a terrific paraphrase! Then it goes on to talk about humiliation and what it means to be messy. ‘Love’ is a word, a noun, and a form of address here. ‘Love’ signifies various lovers or one talked about as his personal archive of sexual experience and love experience. Here’s another: “Me: I’m a mess. Love: No, you came here to get messed up.” I found this kind of dialogue that moves between self and love very cute and funny.

Some of the appearances in this book are very funny. There’s one by the political commentator Errol Morris. If you live in New York, you know who that is.

We’ve interviewed him!

He appears in this book in a meditation on an interview between Errol Morris and Donald Rumsfield. What a curious, beautiful surprise that just comes right out of Aaron’s personal memory. There’s also a lot of stuff about BDSM here, too, so it appears to be a coming out of one’s feelings about bondage as well. It doesn’t try to titillate; it’s just part of the material of the text, in a way. Lots of interesting things get said.

Why do you think Kunin picked George Herbert?

He teaches primarily in Renaissance literature. So this is his area of scholarly expertise.

Next, you chose day pulls down the sky/a filament in a gold leaf by Asiya Wadud and Okwui Okpokwasili. Tell us more about this very unique book.

As I made my list, I realized that almost all of these poets are thinking about and working with materials that are outside of the official boundaries of poetry. How do you make poetry right now? All of these books are asking that question in a really beautiful way.

This one is a collaborative book. Asiya Wadud, who I mentioned to you is a caregiver to my son sometimes, teaches poetry to small children. I knew Asiya as a poet before I knew anything about her professional job as a teacher of poetry to small children at Saint Ann’s School in New York, but that’s what her job is—she’s amazing with little kids. One of her other talents is that she’s a beautiful writer. Her first book, Crosslight for Youngbird (2018), is great.

Day pulls down the sky/a filament in a gold leaf is a collaboration between Asiya Wadud and Okwui Okpokwasili, who recently won a MacArthur grant. She’s known as a dancer and movement artist. Working together with Okwui’s songs, Asiya in meditation on those songs would produce poems. One of the most interesting things about this book is how this collaboration has been orchestrated on the page. I am interested in the way that the poems’ appearance on the page demonstrates a form of conversation and also suggests a modality of performance. Asiya’s poem will be at the top, looking like a poem, and then in another font at the bottom will be a song upon which she has meditated in composition of the poem.

What would you call that? It’s not multimedia, but it’s hard to describe.

You might think about it as a text for performance, like a libretto. It’s a book that thinks deeply about what song is, and poetry’s relationship to song. What is a chorus? What does it mean to be in a multivocal performance mode or composition mode? What does it mean to have a single voice? Those are very interesting questions, and they’re very profoundly realized in the book itself.

This is more of a general question, but for someone reading this interview who might have no experience of reading, for want of a better term, ‘non-traditional’ or experimental poetry, what would you say to a beginner? I know the question of difficulty is a tired one, but I’m always curious to hear poets’ opinions about how to navigate an entry point. Because someone might well find the concept of these books fascinating but not consider themselves equipped to fully engage with and understand them.

One of the reasons I picked these books to talk about is that they’re independently delightful at the level of language. There isn’t anything incomprehensible or unintelligible in these books. All the words are words that are known to us. They all have a kind of magical reality to them, but that’s actually the great thing about reading a work like this. I don’t think they push back against our understanding with disinterest. These are all welcoming texts that are interested in relationships—relationships with readers, too.

“Poetry is not here to make your day better, or to confirm what you already know about your day”

Poetry is not here to make your day better, in my view. Or to confirm what you already know about your day. Poetry is here to stir your linguistic facilities, to give you the equipment to understand words differently every minute. A book like Love Three is incredibly easy to read. It’s the kind of book I would give someone for Christmas—someone who was a serious reader. It would blow their mind.

Right. Who says George Herbert criticism can’t be fun?

Exactly. Or sexy, which is one of the questions of the text: what’s the relationship between poetry and pleasure and desire? And that’s the very question you’re asking me.

I know you also wanted to mention some titles that didn’t make your list but which you wished you could include. Let’s talk about those and also how you came to select your final recommended title, Avery R. Young’s neckbone.

Terrance Hayes told me about neckbone. I asked a bunch of people ‘What was your favorite book this year? What comes to mind?’ and Terrance said neckbone, and I thought, ‘I’ve never heard of this!’

Hayes’s book American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin (2018) was recommended in last year’s roundup.

I’m not surprised, because it’s an excellent book. He also published a terrific book with Wave last year, To Float in the Space Between: A Life and Work in Conversation with the Life and Work of Etheridge Knight (2018). That’s another critical memoir in a similar vein to Kunin’s Love Three. It was gorgeous.

Avery Young’s neckbone was great; Benjamin Krusling’s I have too much to hide (which is forthcoming) is excellent. Stephanie Young’s Pet Sounds, which is a book that’s really engaged with popular music, was terrific—it’s one of the books that made me smile this year. And lastly, this anthology that came out this year, Letters to the Future: Black Women, Radical Writing, was really terrific and the first of its kind. (Full disclosure, I have a poem in it.) There are many writers who really are unknown to most people in this book. It’s edited by Erica Hunt and Dawn Lundy Martin, who are well known to people who follow contemporary American poetry.

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you're enjoying this interview, please support us by donating a small amount.

Letters to the Future’s got a little bit of everything in it. I’m just going to read you some of the folks who appear in here: Octavia Butler, Betsy Fagin, Ruth Ellen Kocher, Robin Coste Lewis, Lillian Yvonne Bertram, LaTasha N. Nevada Diggs, r. erica doyle, Adjua Gargi Nzinga Greaves, Duriel E. Harris, Harryette Mullen, giovanni singleton, Evie Shockley, Khadijah Queen, Wendy S. Walters, Adrian Piper, Yona Harvey, Harmony Holiday, Tracie Morris, Claudia Rankine, Deborah Richards, Metta Sáma, Kara Walker, Renee Gladman, Tonya Foster, Julie Patton, Akilah Oliver . . . and the poems of the editors, too! I just love that.

I think Ben Krusling’s digital book I have too much to hide is on the cutting edge of what poetry is going to do the next 10 years. Young poets who might not have yet published their first books are thinking about art and performance in a way that is unwilling to separate the two. (Asiya Wadud and Okwui Okpokwasil’s book is one example of this. Although it’s pretty contextually confined, I think performances of the work would make clear what this connection is or can be.)

“We’re going to see more and more multimedia poetry”

We’re going to see more and more multimedia poetry, and I don’t mean ‘multimedia’ like ‘Oh, there’s also a video.’ I mean people who are thinking deeply about the connections between what the generative nature of language is, what poetry does in terms of its rearrangement and re-constitutive properties, and how other arts (visual and digital) and other institutions (like the art world) will affect the capacity of poetry to know itself. What is the technology of poetry today, especially institutional technology? Benjamin Krusling’s work is an important harbinger of what is coming.

The same is true of neckbone. You look at it and think, this is a book that primarily deals in black vernacular. But does it? It’s so deeply fixed in a visual tradition that it really troubles the connection between orality and visuality. It asks those questions directly: what’s the connection between hearing and seeing? When you hear a black person speak, does it also mean you can see them? It’s introduced by Theaster Gates, who works out of Chicago. He’s a major public artist who comes from architecture. I thought it was interesting that he would make an appearance as an endorser of this book. It’s also another one that made me laugh—it has jokes and it’s very funny; one of its epigraphs is a Richard Pryor quote.

The books you’ve chosen seem to be pushing the bounds of what poetry is. It makes me think a lot about the work that this art form is trying to do today, and wonder why much of its more experimental voyages seem to stay on the fringes of poetic discourse.

Poetry for me is not about orthodoxy; it’s not about meeting people’s expectations. What poets today who I think are interesting are doing is raising questions about why poetry continues to be relevant to us. What is it that poetry does that we cannot do without as a society? Socially and intellectually, what does it do for us that cannot be done in other places? That’s where the action is in poetry. For me, I’m a poet, I’m not a literary critic and I don’t run a magazine. So in a way, whether people read the poetry is secondary to me. It has always been the case, at least in the United States, that poetry does not have a large readership.

“Poetry for me is not about orthodoxy; it’s not about meeting people’s expectations”

When you ask why it’s slow to catch on—it’s because it’s art. It’s hard to challenge anyone’s expectations about anything. And I don’t mean because the language is difficult; like I said, sometimes it’s super simple. I can open any of these books and find words that are not hard to understand.

What’s harder is having your fundamental idea of reality troubled, or your expectations for what poetry is disturbed, you’re saying?

What’s difficult is related to the actual experience of what difficulty is. It is not affirming the ease that ideology tells us life ought to be: it’s what life really is. For me, I don’t think of myself in a conceptual camp at all. I don’t think of myself as interested in testing people’s capacity to bear the presentation. I actually want people to bear the presentation so that we can have a conversation about it. I want people to be able to engage with the works as emotionally as I do. These things make me cry; they make me laugh; they make me want to throw the book across the room.

Those are the experiences of reading I want to convey to everybody else. It’s not, ‘Oh, it’s obscure’; this actually looks like the texture of real life to me. And encountering anyone’s mind is so rewarding. The thing about a book like Civil Bound that’s so terrific is that you are obviously in the presence of someone whose imagination is singular. When I sat down to read it for the first time, I could hear Myung’s voice speaking the words of the poem to me. I thought, ‘This is a voice I would like to know more about.’ I realize it’s my professional job to read poems and to help other people understand why they should. But I’ve taught poetry both to people who are in remedial composition classes and also graduate students, and those people do not have different experiences of the poem. Everybody is able to reach into the poem emotionally and to understand the words. And that’s all there is.

December 31, 2019

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at editor@fivebooks.com