When historians write the book on early 21st-century design, they will no doubt aim the bulk of their scholarship at the aughts. After all, the sunny, experimental designs of Y2K presaged many of the computing paradigms in use today, and the iPhone, possibly the most influential design object of all time, was released in 2007.

But it would be a mistake to discount design’s impact in the 2010s. We may not be able to point to a single object that reshaped the world as fully and as swiftly as the iPhone, but the 2010s saw the introduction of Tesla’s Model S, which used seductive design to push the entire car industry to rethink its dependence on fossil fuels; the proliferation of the pussy hat, which gave visceral form to the #metoo movement; and the rise of social media platforms, which have arguably done more to manipulate our social and political reality than any other recent invention. If the ’00s were design’s formative childhood in the third millennium, the 2010s were its wild teen years—more mature and confident, sure, but also prone to screwing up royally.

Here, we’ve tapped designers and design thinkers from a range of disciplines, from technology design and branding to transportation and urbanism, to identify the most important products, services, and design ideas of the 2010s. Their responses aren’t just an exercise in nostalgia; they offer clues about where design is headed as a new decade looms.

Pussy Hat instructions

It was conceived on Thanksgiving weekend in the wake of the 2016 presidential elections by three women: a screenwriter, an architect, and the owner of a knitting supply shop in Atwater Village, California. Kat Coyle transformed Krista Suh and Jayna Zweiman’s idea of wearable protest into 17 lines of precise instructions, and the internet did the rest. As a symbol, it was an imperfect, ambiguous metaphor, a handmade response to the red MAGA hat. But there was no denying the visual power of a city inundated by a sea of pink, as hundreds of thousands of women flooded into Washington DC the morning after Donald Trump’s inauguration. For a single day, the Pussy Hat was the nation’s most powerful monument. —Michael Bierut, partner, Pentagram

Tesla Model S

First introduced in 2012, the Model S accelerated the advent of sustainable transport like no other design and made the whole car industry rethink its oil-consuming future. Changing a design to encourage replacement consumerism is no longer responsible. We have to reduce, reuse, and rethink. —Paul Priestman, chairman, PriestmanGoode

#BlackLivesMatter

On July 13, 2013 a jury acquitted George Zimmerman of the murder of a 17-year-old unarmed African-American high school student named Trayvon Martin. In response, Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi created a movement-building effort they titled #BlackLivesMatter. The movement continued to grow after the 2014 deaths of Michael Brown (which also resulted in protests in Ferguson, St. Louis) and Eric Garner in New York City. Today, Black Lives Matter has become a worldwide ideological and political movement to protest how Black lives are systematically and intentionally targeted. It also introduced a cultural shift wherein—for the first time in modern history—the most popular, influential brands are being created by the people and for the people for the sole purpose of changing the world and making it a better place. You can’t buy these brands in a supermarket or drugstore or mall. Now, our greatest innovations are the creation of brands that can make a difference in our lives and reflect the kind of world we want to live in. The #BlackLivesMatter effort has subsequently become a beacon in the darkness of our times and a statement of accountability in our culture. —Debbie Millman, founder, Design Matters

iPad

The iPad was largely mocked when it was first introduced by Steve Jobs a decade ago, but in short order, it created its own market sector: the tablet. In the years since, it has made computing more accessible and intuitive for all ages, with a sleek simplicity that has only improved relative to its rivals (save for the tortures of iOS 13). For designers, it has become an indispensable tool, especially when paired with the drawing ease of the Apple Pencil. The clear future for this technology is a tablet that can fold or roll into a pocket, that can project, and that someday may replace both the phone and the desktop as a singular personal device that could hopefully diminish our electricity use and e-waste. Proof that consumers don’t always know what they want until they want it, the iPad is the apotheosis of Jobs’s ability to combine touch and tech in a package for which we could only heretofore dream. —Vishaan Chakrabarti, founder, Practice for Architecture and Urbanism

Gov.UK

I choose GOV.UK, the website designed by the UK Government Digital Service, which comprehensively redesigned the way in which citizens of the UK accessed government services. It’s a brilliant example of design genuinely making life better for everyone—it’s not pretty, it’s not selling anything, it’s not design for other designers. It just makes things better. And it’s been replicated all around the world. —Patrick Burgoyne, CEO, D&AD

Streaming media

In a sense, the success of these all-you-can-eat services, like Netflix and Spotify, was inevitable, but the design of each was critical to how quickly they conquered the world. They perfected the notion of binging and endless playlists and, in less than a decade, totally reconfigured our relationship with media. Future generations will barely recognize the era of music, television, and movies that came before them—for better or worse. —Khoi Vinh, principal designer, Adobe

DJI Phantom UAV

The Shenzhen-based company DJI released its first iteration of its Phantom drone in 2013. The low-cost, remote-operated quadcopter mounted with a camera quickly generated a global fan base of amateur and professionals alike, netting the company a multibillion-dollar valuation. Not only has DJI changed photography and film-making through ubiquitous aerial imagery, it’s opened up the skies to a range of both positive and problematic applications, including firefighting, spatial research, disaster aid, surveillance, protest, and violence. —Brendan Cormier, senior design curator, V&A

Manipulative social platforms

Design is, ultimately, an exercise in manipulation. It attempts to intentionally trigger a response from the user in order to achieve an outcome. Over the past decade, nothing comes close to the nefarious design by bad actors and the oftentimes unintentional bias of AI-based algorithms. These were amplified by the Clouseau-like complicity of the digital and business model designers of the social platforms of the 2010s. Users were manipulated—by design—to like, friend, and forward provocative memes that have enflamed passions on all sides of every argument and given comfort to lies. And therein rests our next great design challenge: ensuring accessible provenance of critical data and designing for trust and fairness. —Phil Gilbert, general manager of design, IBM

The 2018 designer babies

By far the most simultaneously brilliant, audacious, and terrifying design of the last decade were the genetically edited “designer babies” of 2018—the offspring production of Chinese researcher He Jiankui. In 2011, prescient NASA scientists upheld the mantle of “most plausible” science fiction movie ever made to 1997’s Gattaca (the title itself a clever spin on G-A-C-T, the four base pairs of DNA); now we know they were right on target, and writer-director Andrew Niccol is now our contemporary Nostradamus. —Forest Young, global principal, Wolff Olins

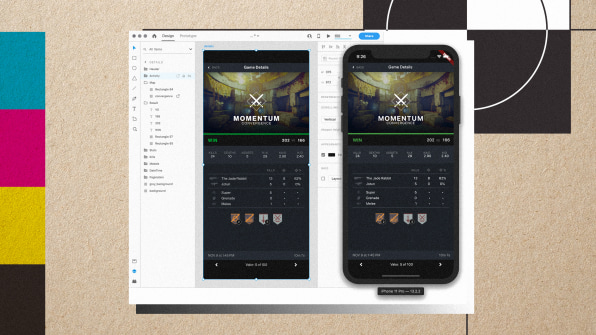

Flutter/ Dart

Distributing work in the world of computational art and design has been, on the one hand, facilitated by the web but also reset by the smartphone revolution. While in the beginnings of the public internet we were fighting just the browser wars, we now need to maintain code across multiple browsers and natively on iOS and Android, to start. Flutter/Dart points to one of the emerging ways by which we can design computational experiences that deploy to all platforms at once—this has the potential to not only save time, but it can ultimately free up our energies to get to the next level of design in the computational era. —John Maeda, chief experience officer, Publicis Sapient

Emoji keyboard

Emoji are ubiquitous. Although they originated in the late 1990s, it wasn’t until 2010 that emoji were recognized by Unicode Consortium (the global regulator that maintains digital text standards) as a communication system for standardization. This opened the door for Apple to introduce the first emoji keyboard to its iOS in 2011, with Android closely following. Emoji keyboards gave users direct access to emoji on their devices, enabling a global, visual language for the digital era to take root. Not only do emoji add emotional nuance to digital text, they convey information across language barriers. New emoji are added annually, including skin-tone modifiers, accessible emoji, gender-neutral people, flags and religious symbols, and much more. Emoji signify inclusion and representation. They facilitate communication and cultural visibility. Emoji are a mirror of us, pointing to the importance of digital communication and representation in the decade ahead. —Andrea Lipps, curator, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

The professionalization of data

Data went public this past decade and forever changed our expectations and experiences for how we measure and understand our world. Before 2010, most data was either in spreadsheets or poorly structured databases on private servers. That changed when President Obama took office. He created the first Open Government Initiative, which led to the launch of data.gov by US CIO Vivek Kundra in May of 2009. By 2010 the floodgates opened, and data from all types of sources started coming online. I consider this past decade to be the time when data visualization and data science became “professionalized” practices. I hope the 2020s will bring these practices together more strategically to help us save our most vulnerable assets: our planet and our democracy. —Lisa Strausfeld, founder, Informationart

The neuromorphic chip

The neuromorphic chip is silicon designed to mimic the form of the human brain. This game-changing architecture transforms the way our devices process information, moving them closer to the way our brains process information. Neural networks can now be etched into silicon not unlike the billions of neurons and synapses that form our nervous system and brain. This means software and data no longer have to be processed on different chips, they can be stored and processed on the same chip—saving significant time, energy and space. Our modern world, already powered by software, is about to change in a really big way. —Imran Chaudhri, former Apple designer and founder, Humane

Sustainability

For me, the greatest achievement of this decade precludes the most important and crucial design work of the next decade: sustainability. During the 2010s, far from enough was created to demonstrate a sustainability global movement. Nevertheless the companies that successfully built lower-carbon design businesses at scale will be remembered—from Tesla demonstrating that the electric car is a good business and an even better experience, to Ikea launching kitchens made of recycled bottles and simplifying its assembly with its tool-less push-fit system, to Stella McCartney’s “vegan” fashion to prefab homes finally becoming mainstream while reducing waste in traditional construction by 80%. These sustainability pioneers are successful companies that show the way forward for business. —Yves Béhar, founder, fuseprojectWhat do you think were the most important designs of the 2010s? Tweet at us or write to CoDTips@fastcompany.com.