In the software world, “waterfall” is commonly used to describe a style of software process, one that contrasts with the ideas of iterative, or agile styles. Like many well-known terms in software it's meaning is ill-defined and origins are obscure - but I find its essential theme is breaking down a large effort into phases based on activity.

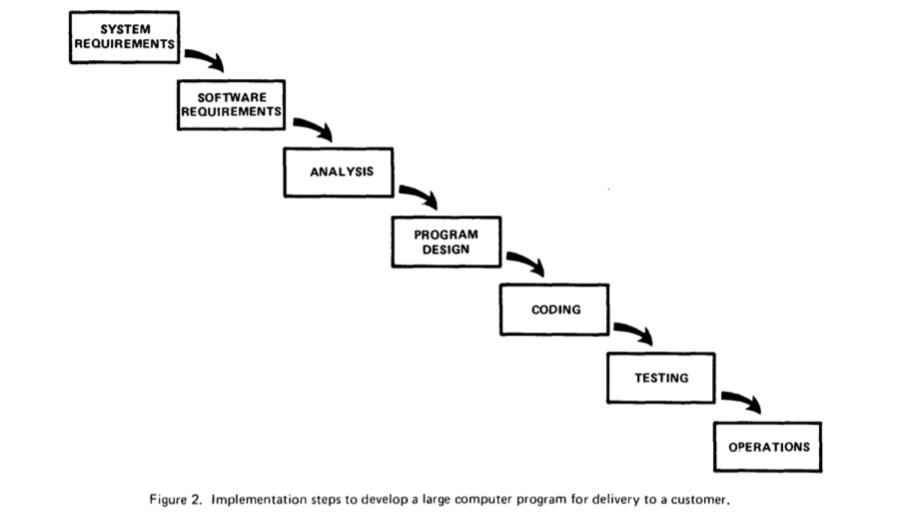

It's not clear how the word “waterfall” became so prevalent, but most people base its origin on a paper by Winston Royce, in particular this figure:

Although this paper seems to be universally acknowledged as the source of the notion of waterfall (based on the shape of the downward cascade of tasks), the term “waterfall” never appears in the paper. It's not clear how the name appeared later.

Royce’s paper describes his observations on the software development process of the time (late 60s) and how the usual implementation steps could be improved. [1] But “waterfall” has gone much further, to be used as a general description of a style of software development. For people like me, who speak at software conferences, it almost always only appears in a derogatory manner - I can’t recall hearing any conference speaker saying anything good about waterfall for many years. However when talking to practitioners in enterprises I do hear of it spoken as a viable, even preferred, development style. Certainly less so now than in the 90s, but more frequently than one might assume by listening to process mavens.

But what exactly is “waterfall”? That’s not an easy question to answer as, like so many things in software, there is no clear definition. In my judgment, there is one common characteristic that dominates any definition folks use for waterfall, and that’s the idea of decomposing effort into phases based on activity.

Let me unpack that phrase. Let’s say I have some software to build, and I think it’s going to take about a year to build it. Few people are going to happily say “go away for a year and tell me when its done”. Instead, most people will want to break down that year into smaller chunks, so they can monitor progress and have confidence that things are on track. The question then is how do we perform this break down?

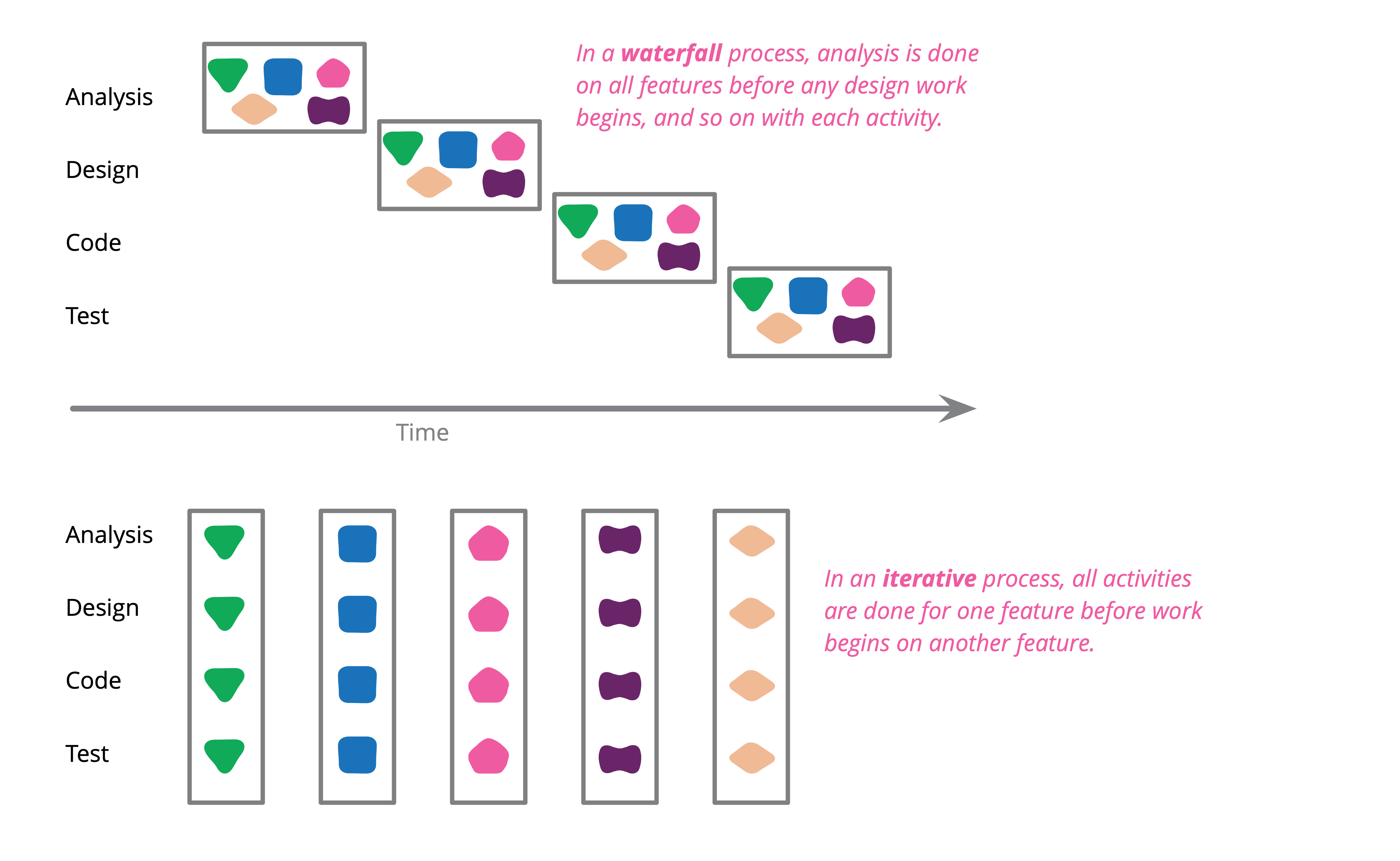

The waterfall style, as suggested by the Royce sketch, does it by the activity we are doing. So our 1 year project might be broken down into 2 months of analysis, followed by 4 months design, 3 months of coding, and 3 months of testing. The contrast here is to an iterative style, where we would take some high level requirements (build a library management system), and divide them into subsets (search catalog, reserve a book, check-out and return, assess fines). We'd then take one of these subsets and spend a couple of months to build working software to implement that functionality, delivering either into a staging environment or preferably into a live production setting. Having done that with one subset, we'd continue with further subsets.

In this thinking waterfall means “do one activity at a time for all the features” while iterative means “do all activities for one feature at a time”.

If the origin of the word “waterfall” is murky, so is the notion of how this phase-based breakdown originated. My guess is that it’s natural to break down a large task into different activities, especially if you look to activities such as building construction as an inspiration. Each activity requires different skills, so getting all the analysts to complete analysis before you bring in all the coders makes intuitive sense. It seems logical that a misunderstanding of requirements is cheaper to fix before people begin coding - especially considering the state of computers in the late 60s. Finally the same activity-based breakdown can be used as a standard for many projects, while a feature-based breakdown is harder to teach. [2]

Although it isn’t hard to find people explain why this waterfall thinking isn’t a good idea for software development, I should summarize my primary objections to the waterfall style here. The waterfall style usually has testing and integration as two of the final phases in the cycle, but these are the most difficult to predict elements in a development project. Problems at these stages lead to rework of many steps of earlier phases, and to significant project delays. It's too easy to declare all but the late phases as "done", with much work missing, and thus it's hard to tell if the project is going well. There is no opportunity for early releases before all features are done. All this introduces a great deal of risk to the development effort.

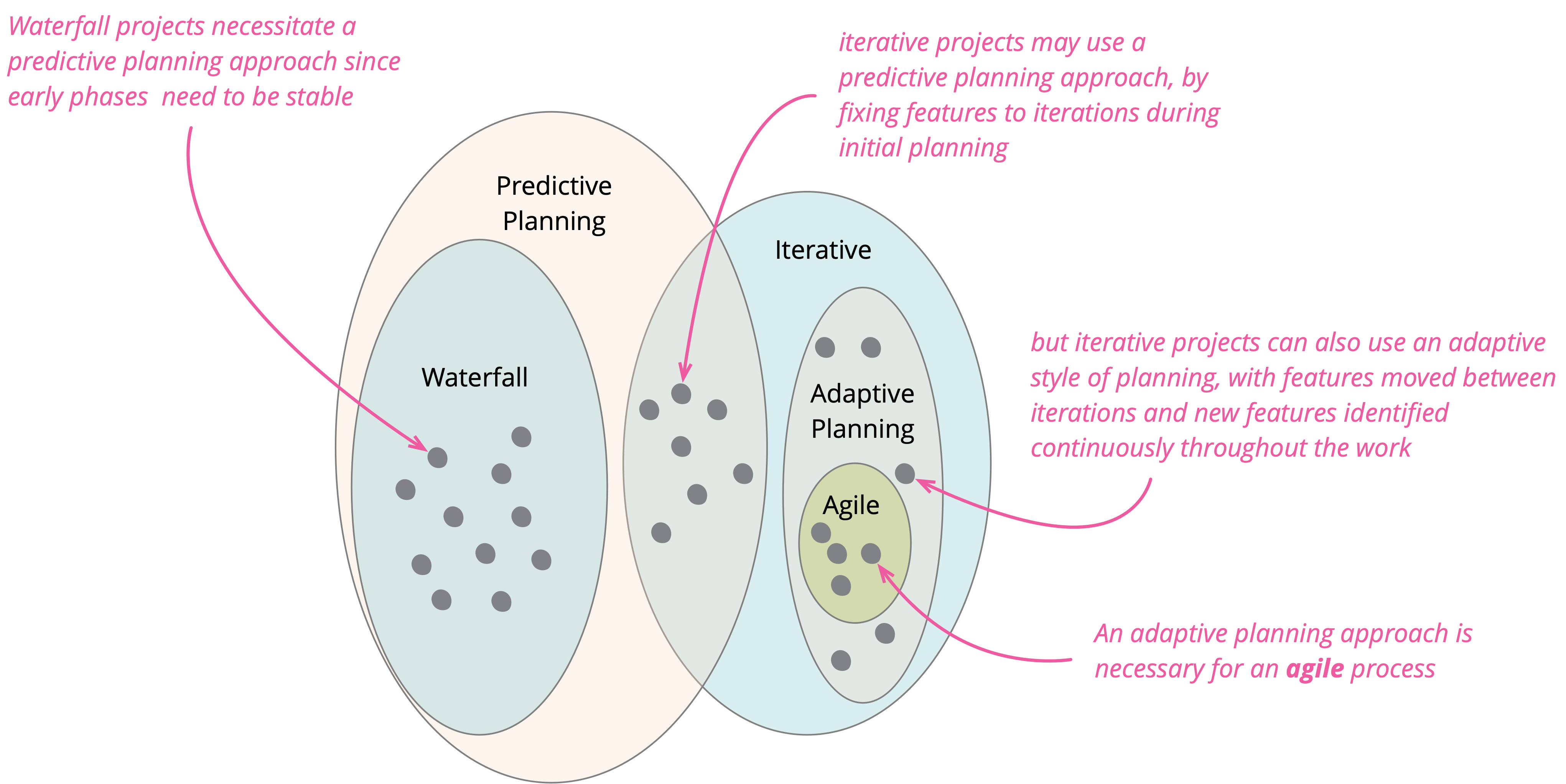

Furthermore, a waterfall approach forces us into a predictive style of planning, it assumes that once you are done with a phase, such as requirements analysis, the resulting deliverable is a stable platform for later phases to base their work on. [3] In practice the vast majority of software projects find they need to change their requirements significantly within a few months, due to everyone learning more about the domain, the characteristics of the software environment, and changes in the business environment. Indeed we've found that delivering a subset of features does more than anything to help clarify what needs to be done next, so an iterative approach allows us to shift to an adaptive planning approach where we update our plans as we learn what the real software needs are. [4]

These are the major reasons why I've glibly said that "you should use iterative development only in projects that you want to succeed".

Waterfalls and iterations may nest inside each other. A six year project might consist of two 3 year projects, where each of the two projects are structured in a waterfall style, but the second project adds additional features. You can think of this as a two-iteration project at the top level with each iteration as a waterfall. Due to the large size and small number of iterations, I'd regard that as primarily a waterfall project. In contrast you might see a project with 16 iterations of one month each, where each iteration is planned in a waterfall style. That I'd see as primarily iterative. While in theory there's potential for a middle ground projects that are hard to classify, in practice it's usually easy to tell that one style predominates.

It is possible for a mix of waterfall and iterative where early phases (requirements analysis, high level design) are done in a waterfall style while later phases (detailed design, code, test) are done in an iterative manner. This reduces the risks inherent in late testing and integration phases, but does not enable adaptive planning.

Waterfall is often cast as the alternative to agile software development, but I don't see that as strictly true. Certainly agile processes require an iterative approach and cannot work in a waterfall style. But it is easy to follow an iterative approach (i.e. non-waterfall) but not be agile. [5] I might do this by taking 100 features and dividing them up into ten iterations over the next year, and then expecting that each iteration should complete on time with its planned set of features. If I do this, my initial plan is a predictive plan, if all goes well I should expect the work to closely follow the plan. But adaptive planning is an essential element of agile thinking. I expect features to move between iterations, new features to appear, and many features to be discarded as no longer valuable enough.g

My rule of thumb is that anyone who says “we were successful because we were on-time and on-budget” is thinking in terms of predictive planning, even if they are following an iterative process, and thus is not thinking with an agile mindset. In the agile world, success is all about business value - regardless of what was written in a plan months ago. Plans are made, but updated regularly. They guide decisions on what to do next, but are not used as a success measure.

Acknowledgements

My thanks to Ben Noble, Clare Sudbury, David Johnston, Karl Brown, Kyle Hodgson, Pramod Sadalage, Prasanna Pendse, Rebecca Parsons, Sriram Narayan, Sriram Narayanan, Tiago Griffo, Unmesh Joshi, and Vidhyalakshmi Narayanaswamy who discussed drafts of this post on our internal mailing list.