Prelude

This is the second post in a three part series that will provide an understanding of the mechanics and semantics behind the scheduler in Go. This post focuses on the Go scheduler.

Index of the three part series:

1) Scheduling In Go : Part I - OS Scheduler

2) Scheduling In Go : Part II - Go Scheduler

3) Scheduling In Go : Part III - Concurrency

Introduction

In the first part of this scheduling series, I explained aspects of the operating-system scheduler that I believe are important in understanding and appreciating the semantics of the Go scheduler. In this post, I will explain at a semantic level how the Go scheduler works and focus on the high-level behaviors. The Go scheduler is a complex system and the little mechanical details are not important. What’s important is having a good model for how things work and behave. This will allow you to make better engineering decisions.

Your Program Starts

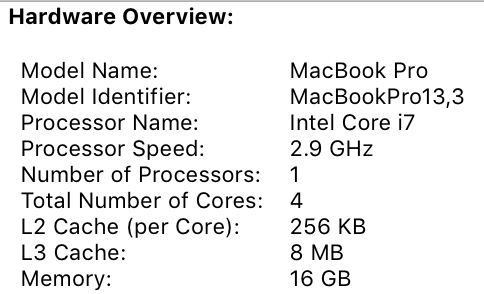

When your Go program starts up, it’s given a Logical Processor (P) for every virtual core that is identified on the host machine. If you have a processor with multiple hardware threads per physical core (Hyper-Threading), each hardware thread will be presented to your Go program as a virtual core. To better understand this, take a look at the system report for my MacBook Pro.

Figure 1

You can see I have a single processor with 4 physical cores. What this report is not exposing is the number of hardware threads I have per physical core. The Intel Core i7 processor has Hyper-Threading, which means there are 2 hardware threads per physical core. This will report to the Go program that 8 virtual cores are available for executing OS Threads in parallel.

To test this, consider the following program:

Listing 1

package main

import (

"fmt"

"runtime"

)

func main() {

// NumCPU returns the number of logical

// CPUs usable by the current process.

fmt.Println(runtime.NumCPU())

}

When I run this program on my local machine, the result of the NumCPU() function call will be the value of 8. Any Go program I run on my machine will be given 8 P’s.

Every P is assigned an OS Thread (“M”). The ‘M’ stands for machine. This Thread is still managed by the OS and the OS is still responsible for placing the Thread on a Core for execution, as explained in the last post. This means when I run a Go program on my machine, I have 8 threads available to execute my work, each individually attached to a P.

Every Go program is also given an initial Goroutine (“G”), which is the path of execution for a Go program. A Goroutine is essentially a Coroutine but this is Go, so we replace the letter “C” with a “G” and we get the word Goroutine. You can think of Goroutines as application-level threads and they are similar to OS Threads in many ways. Just as OS Threads are context-switched on and off a core, Goroutines are context-switched on and off an M.

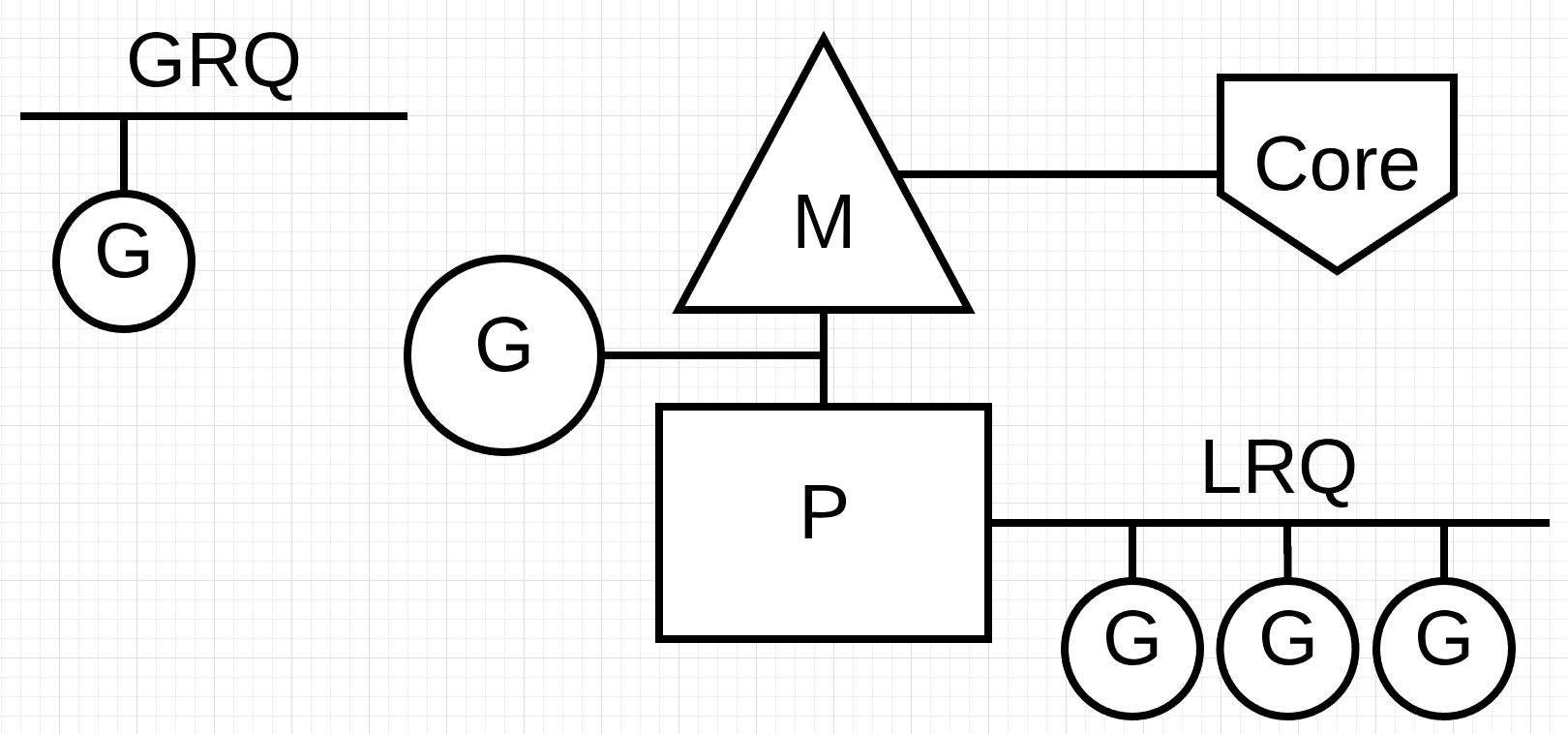

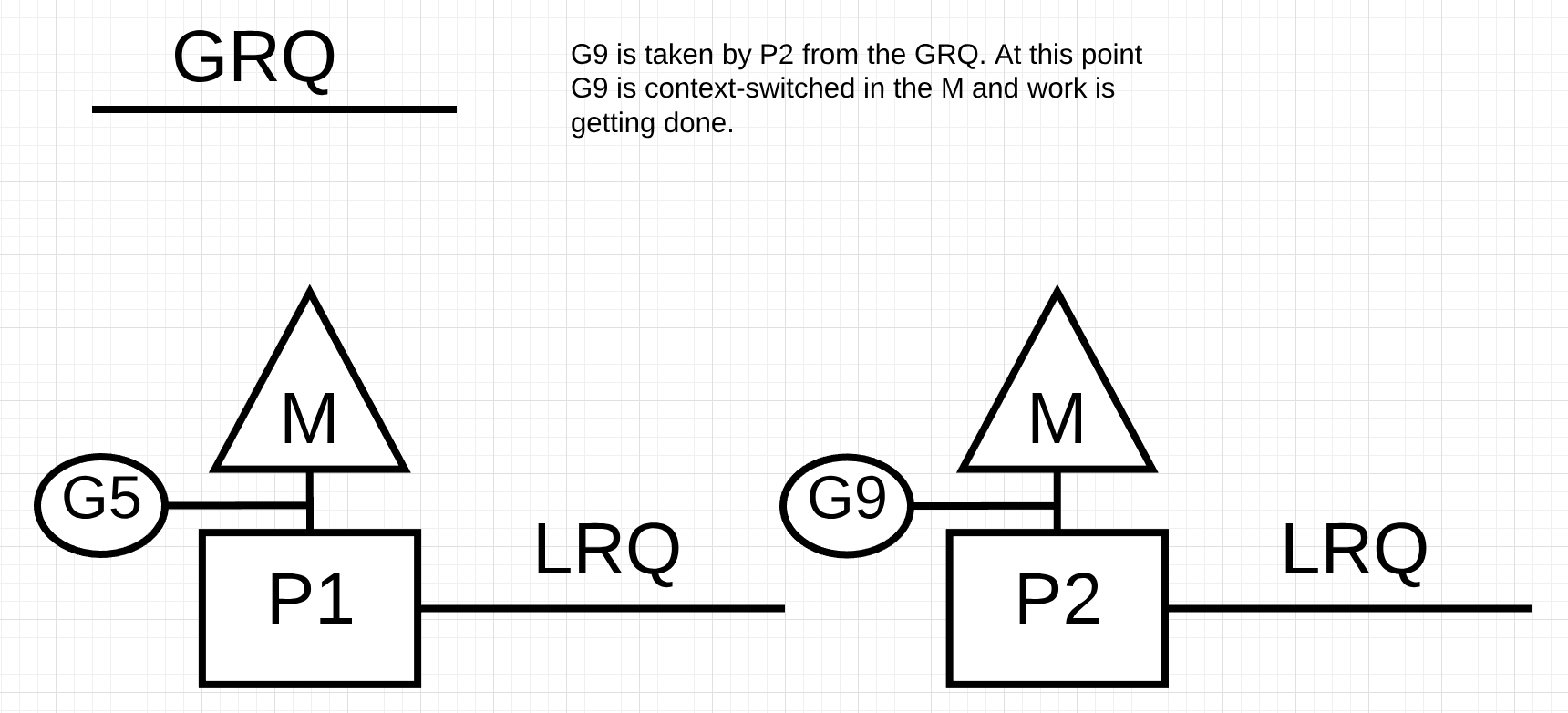

The last piece of the puzzle is the run queues. There are two different run queues in the Go scheduler: the Global Run Queue (GRQ) and the Local Run Queue (LRQ). Each P is given a LRQ that manages the Goroutines assigned to be executed within the context of a P. These Goroutines take turns being context-switched on and off the M assigned to that P. The GRQ is for Goroutines that have not been assigned to a P yet. There is a process to move Goroutines from the GRQ to a LRQ that we will discuss later.

Figure 2 provides an image of all these components together.

Figure 2

Cooperating Scheduler

As we discussed in the first post, the OS scheduler is a preemptive scheduler. Essentially that means you can’t predict what the scheduler is going to do at any given time. The kernel is making decisions and everything is non-deterministic. Applications that run on top of the OS have no control over what is happening inside the kernel with scheduling unless they leverage synchronization primitives like atomic instructions and mutex calls.

The Go scheduler is part of the Go runtime, and the Go runtime is built into your application. This means the Go scheduler runs in user space, above the kernel. The current implementation of the Go scheduler is not a preemptive scheduler but a cooperating scheduler. Being a cooperating scheduler means the scheduler needs well-defined user space events that happen at safe points in the code to make scheduling decisions.

What’s brilliant about the Go cooperating scheduler is that it looks and feels preemptive. You can’t predict what the Go scheduler is going to do. This is because decision making for this cooperating scheduler doesn’t rest in the hands of developers, but in the Go runtime. It’s important to think of the Go scheduler as a preemptive scheduler and since the scheduler is non-deterministic, this is not much of a stretch.

Goroutine States

Just like Threads, Goroutines have the same three high-level states. These dictate the role the Go scheduler takes with any given Goroutine. A Goroutine can be in one of three states: Waiting, Runnable or Executing.

Waiting: This means the Goroutine is stopped and waiting for something in order to continue. This could be for reasons like waiting for the operating system (system calls) or synchronization calls (atomic and mutex operations). These types of latencies are a root cause for bad performance.

Runnable: This means the Goroutine wants time on an M so it can execute its assigned instructions. If you have a lot of Goroutines that want time, then Goroutines have to wait longer to get time. Also, the individual amount of time any given Goroutine gets is shortened as more Goroutines compete for time. This type of scheduling latency can also be a cause of bad performance.

Executing: This means the Goroutine has been placed on an M and is executing its instructions. The work related to the application is getting done. This is what everyone wants.

Context Switching

The Go scheduler requires well-defined user-space events that occur at safe points in the code to context-switch from. These events and safe points manifest themselves within function calls. Function calls are critical to the health of the Go scheduler. Today (with Go 1.11 or less), if you run any tight loops that are not making function calls, you will cause latencies within the scheduler and garbage collection. It’s critically important that function calls happen within reasonable timeframes.

Note: There is a proposal for 1.12 that was accepted to apply non-cooperative preemption techniques inside the Go scheduler to allow for the preemption of tight loops.

There are four classes of events that occur in your Go programs that allow the scheduler to make scheduling decisions. This doesn’t mean it will always happen on one of these events. It means the scheduler gets the opportunity.

- The use of the keyword

go - Garbage collection

- System calls

- Synchronization and Orchestration

The use of the keyword go

The keyword go is how you create Goroutines. Once a new Goroutine is created, it gives the scheduler an opportunity to make a scheduling decision.

Garbage collection

Since the GC runs using its own set of Goroutines, those Goroutines need time on an M to run. This causes the GC to create a lot of scheduling chaos. However, the scheduler is very smart about what a Goroutine is doing and it will leverage that intelligence to make smart decisions. One smart decision is context-switching a Goroutine that wants to touch the heap with those that don’t touch the heap during GC. When GC is running, a lot of scheduling decisions are being made.

System calls

If a Goroutine makes a system call that will cause the Goroutine to block the M, sometimes the scheduler is capable of context-switching the Goroutine off the M and context-switch a new Goroutine onto that same M. However, sometimes a new M is required to keep executing Goroutines that are queued up in the P. How this works will be explained in more detail in the next section.

Synchronization and Orchestration

If an atomic, mutex, or channel operation call will cause the Goroutine to block, the scheduler can context-switch a new Goroutine to run. Once the Goroutine can run again, it can be re-queued and eventually context-switched back on an M.

Asynchronous System Calls

When the OS you are running on has the ability to handle a system call asynchronously, something called the network poller can be used to process the system call more efficiently. This is accomplished by using kqueue (MacOS), epoll (Linux) or iocp (Windows) within these respective OS’s.

Networking-based system calls can be processed asynchronously by many of the OSs we use today. This is where the network poller gets its name, since its primary use is handling networking operations. By using the network poller for networking system calls, the scheduler can prevent Goroutines from blocking the M when those system calls are made. This helps to keep the M available to execute other Goroutines in the P’s LRQ without the need to create new Ms. This helps to reduce scheduling load on the OS.

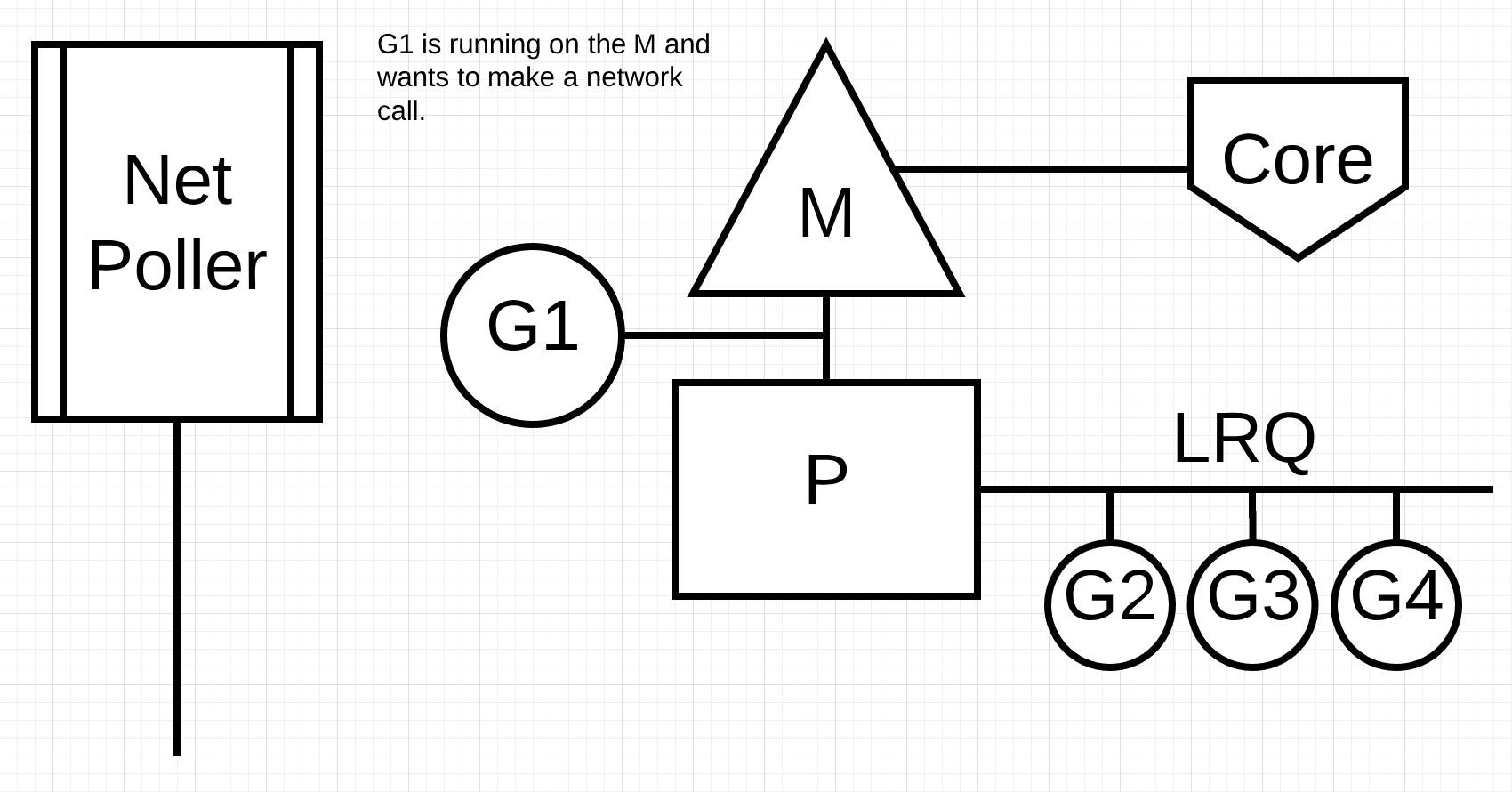

The best way to see how this works is to run through an example.

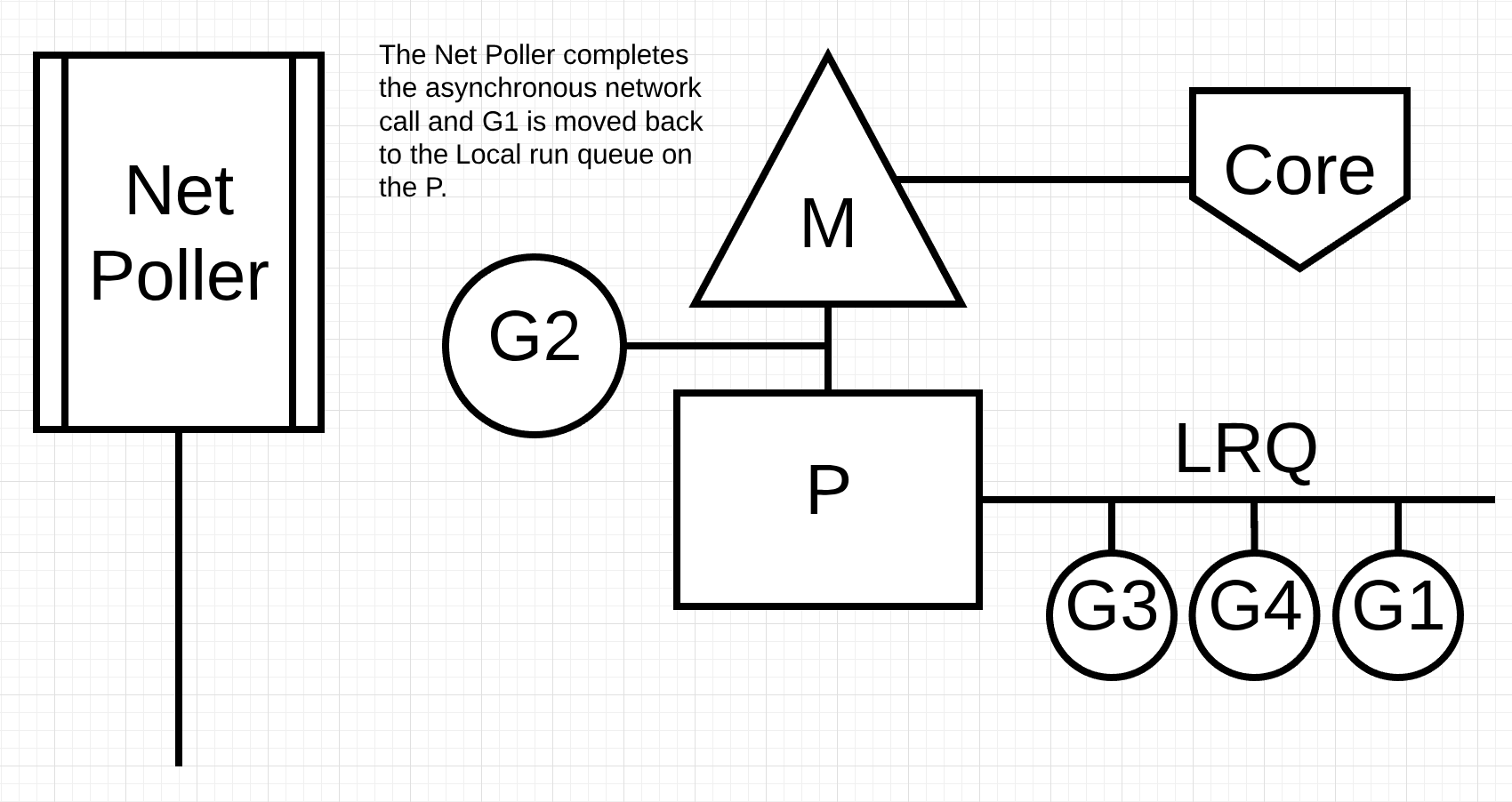

Figure 3

Figure 3 shows our base scheduling diagram. Goroutine-1 is executing on the M and there are 3 more Goroutines waiting in the LRQ to get their time on the M. The network poller is idle with nothing to do.

Figure 4

In figure 4, Goroutine-1 wants to make a network system call, so Goroutine-1 is moved to the network poller and the asynchronous network system call is processed. Once Goroutine-1 is moved to the network poller, the M is now available to execute a different Goroutine from the LRQ. In this case, Goroutine-2 is context-switched on the M.

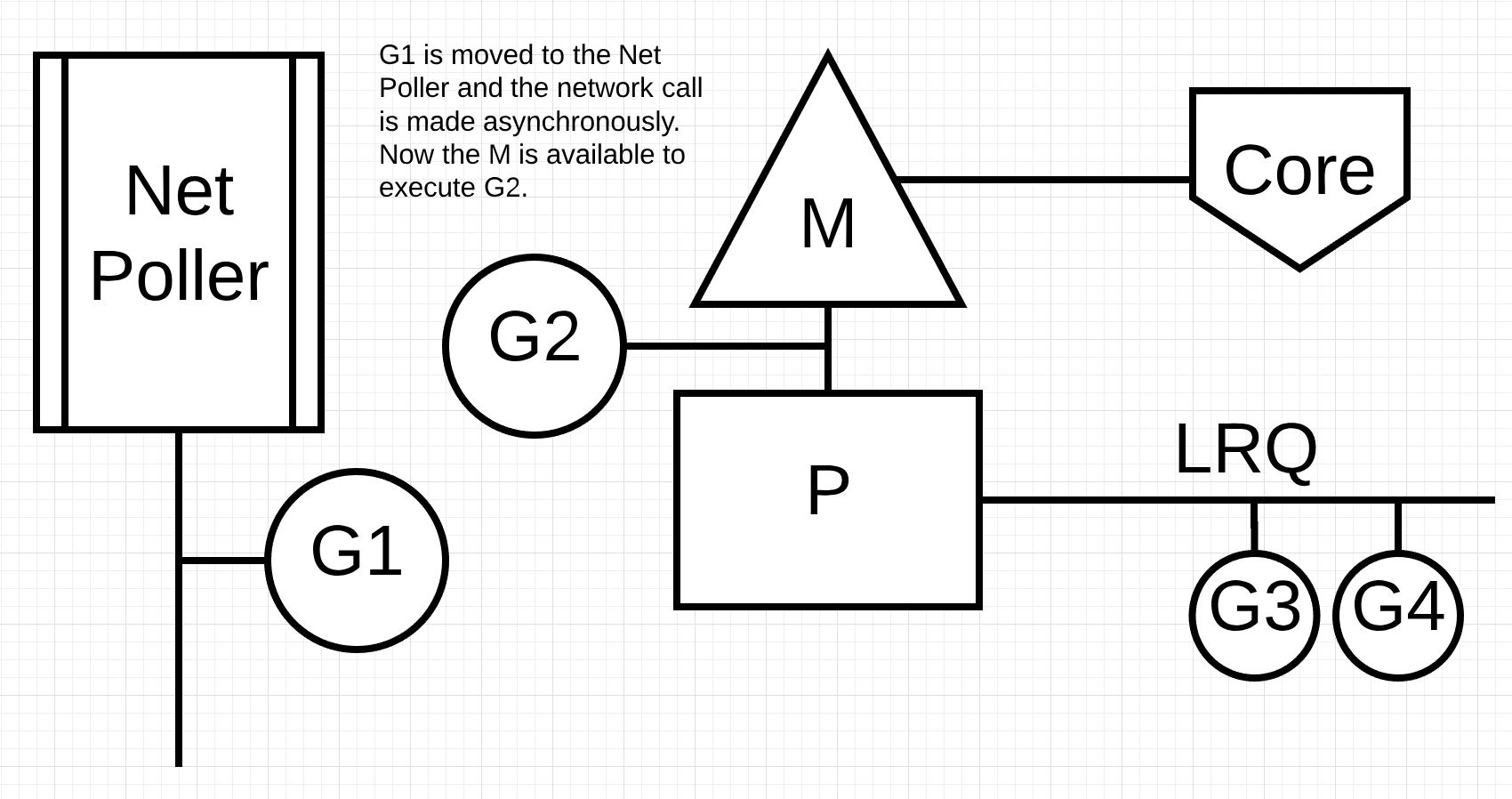

Figure 5

In figure 5, the asynchronous network system call is completed by the network poller and Goroutine-1 is moved back into the LRQ for the P. Once Goroutine-1 can be context-switched back on the M, the Go related code it’s responsible for can execute again. The big win here is that, to execute network system calls, no extra Ms are needed. The network poller has an OS Thread and it is handling an efficient event loop.

Synchronous System Calls

What happens when the Goroutine wants to make a system call that can’t be done asynchronously? In this case, the network poller can’t be used and the Goroutine making the system call is going to block the M. This is unfortunate but there’s no way to prevent this from happening. One example of a system call that can’t be made asynchronously is file-based system calls. If you are using CGO, there may be other situations where calling C functions will block the M as well.

Note: The Windows OS does have the capability of making file-based system calls asynchronously. Technically when running on Windows, the network poller can be used.

Let’s walk through what happens with a synchronous system call (like file I/O) that will cause the M to block.

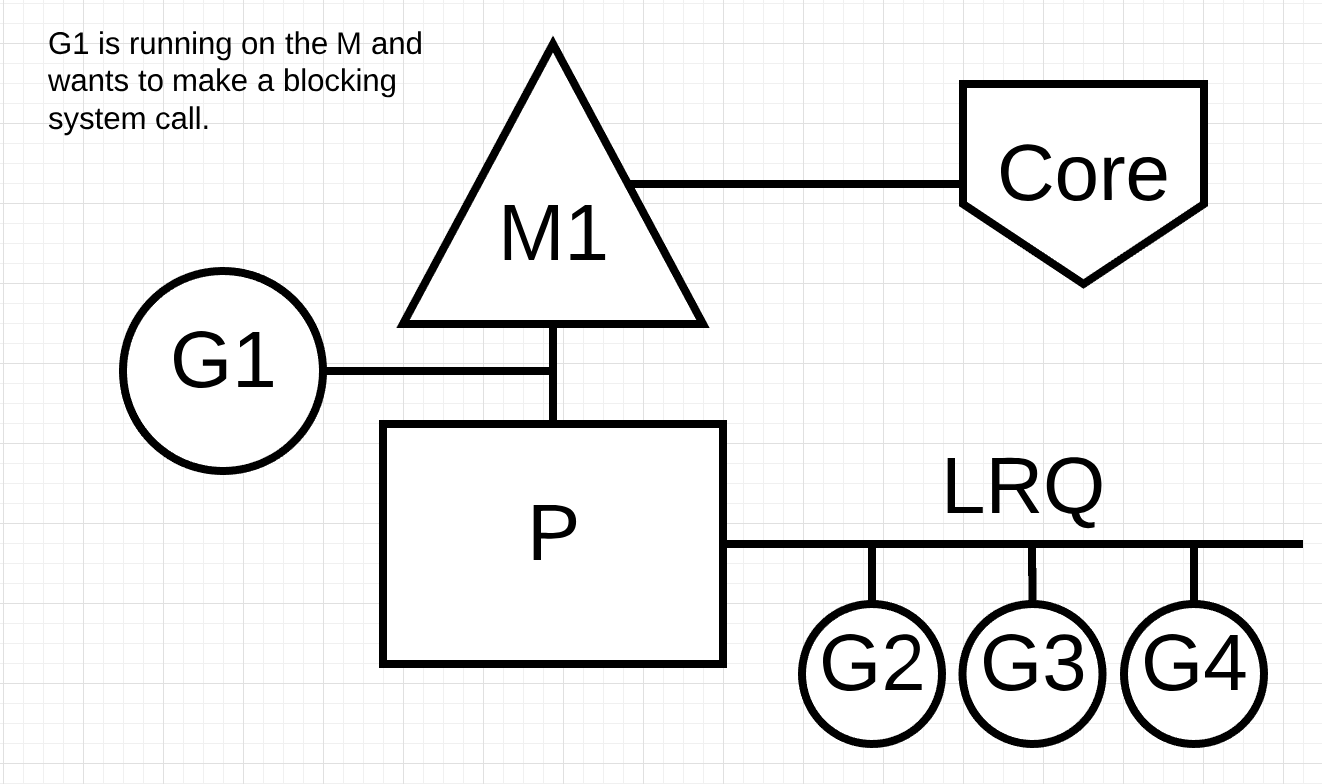

Figure 6

Figure 6 is showing our basic scheduling diagram again but this time Goroutine-1 is going to make a synchronous system call that will block M1.

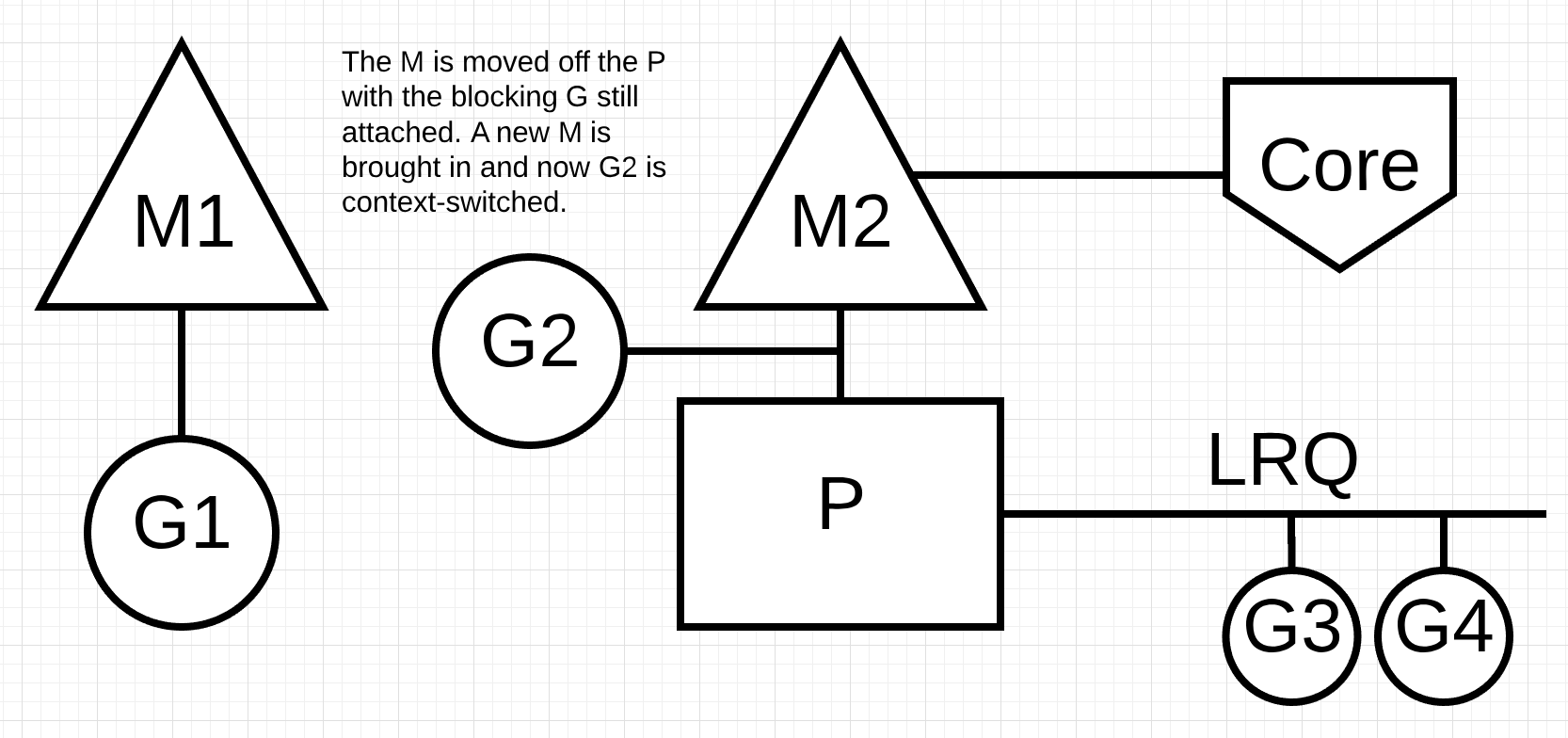

Figure 7

In figure 7, the scheduler is able to identify that Goroutine-1 has caused the M to block. At this point, the scheduler detaches M1 from the P with the blocking Goroutine-1 still attached. Then the scheduler brings in a new M2 to service the P. At that point, Goroutine-2 can be selected from the LRQ and context-switched on M2. If an M already exists because of a previous swap, this transition is quicker than having to create a new M.

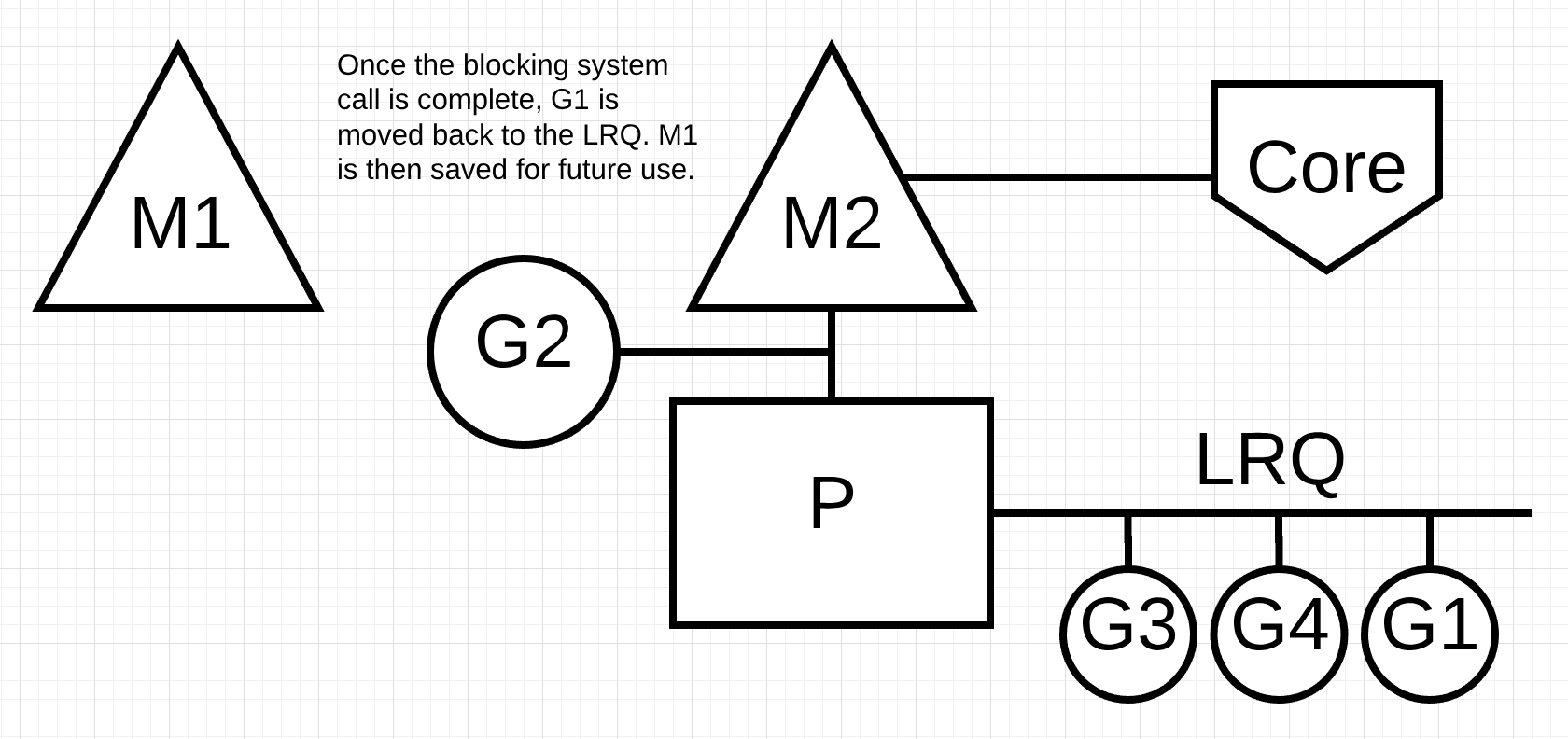

Figure 8

In figure 8, the blocking system call that was made by Goroutine-1 finishes. At this point, Goroutine-1 can move back into the LRQ and be serviced by the P again. M1 is then placed on the side for future use if this scenario needs to happen again.

Work Stealing

Another aspect of the scheduler is that it’s a work-stealing scheduler. This helps in a few areas to keep scheduling efficient. For one, the last thing you want is an M to move into a waiting state because, once that happens, the OS will context-switch the M off the Core. This means the P can’t get any work done, even if there is a Goroutine in a runnable state, until an M is context-switched back on a Core. The work stealing also helps to balance the Goroutines across all the P’s so the work is better distributed and getting done more efficiently.

Let’s run through an example.

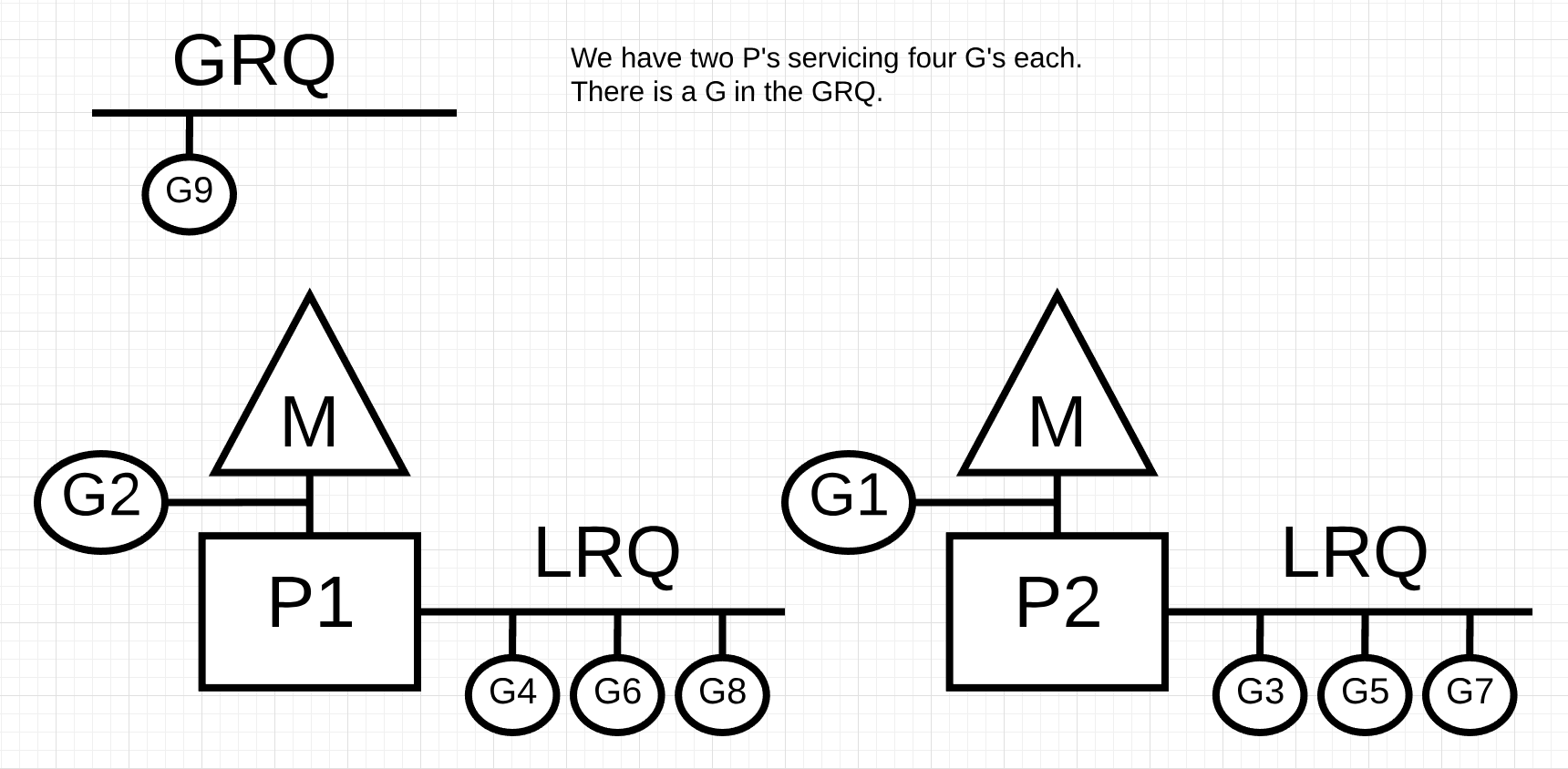

Figure 9

In figure 9, we have a multi-threaded Go program with two P’s servicing four Goroutines each and a single Goroutine in the GRQ. What happens if one of the P’s services all of its Goroutines quickly?

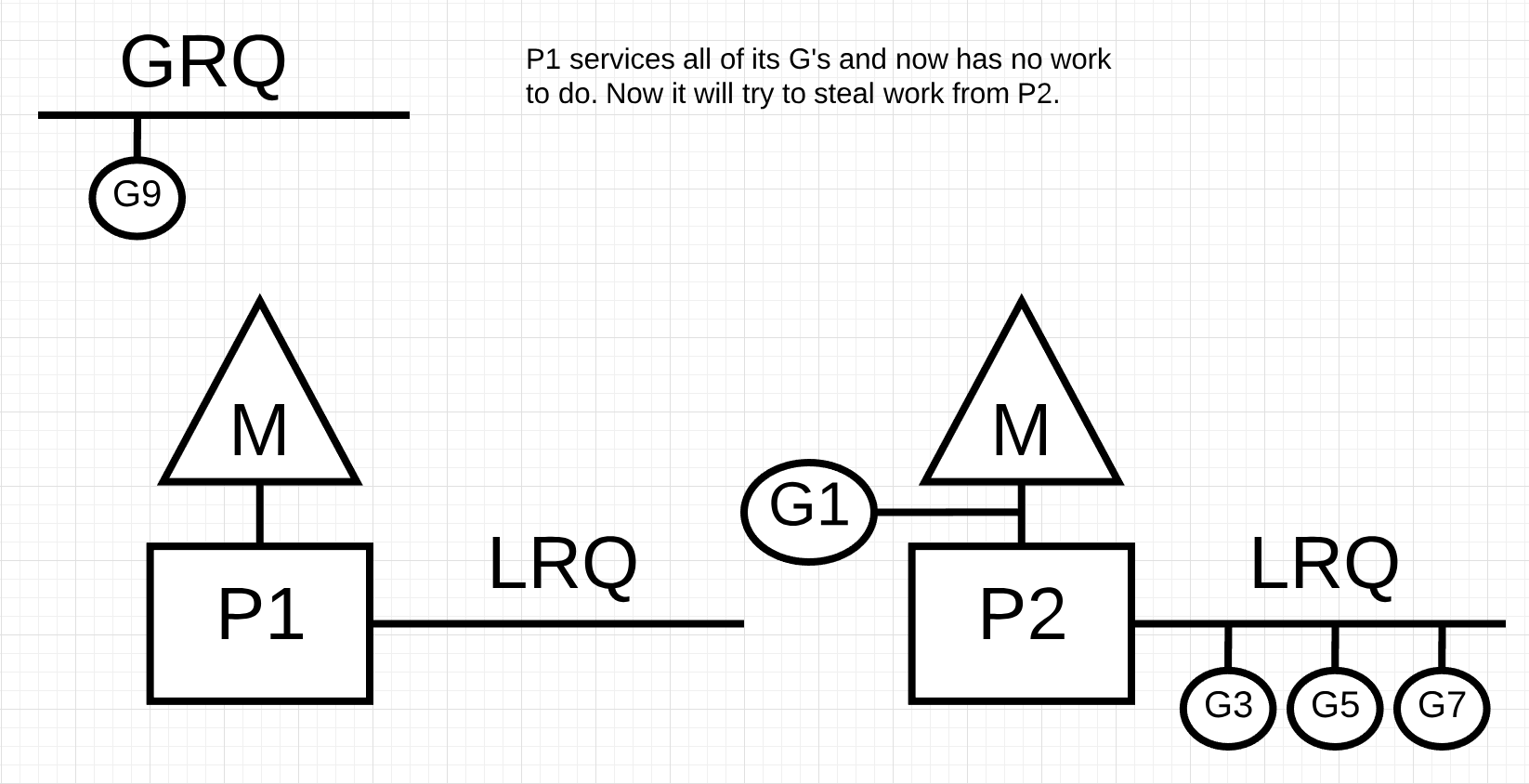

Figure 10

In figure 10, P1 has no more Goroutines to execute. But there are Goroutines in a runnable state, both in the LRQ for P2 and in the GRQ. This is a moment where P1 needs to steal work. The rules for stealing work are as follows.

Listing 2

runtime.schedule() {

// only 1/61 of the time, check the global runnable queue for a G.

// if not found, check the local queue.

// if not found,

// try to steal from other Ps.

// if not, check the global runnable queue.

// if not found, poll network.

}

So based on these rules in Listing 2, P1 needs to check P2 for Goroutines in its LRQ and take half of what it finds.

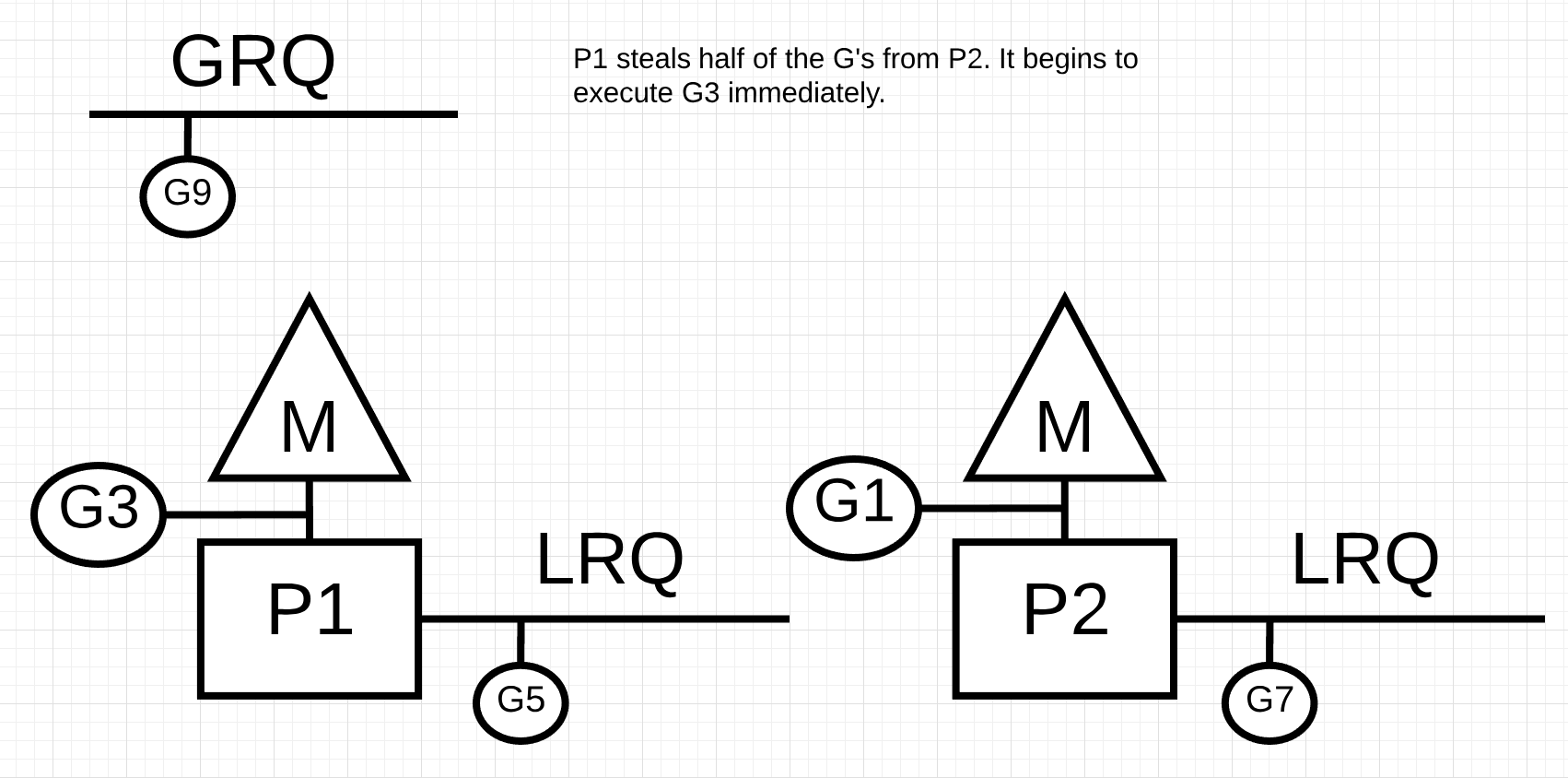

Figure 11

In figure 11, half the Goroutines are taken from P2 and now P1 can execute those Goroutines.

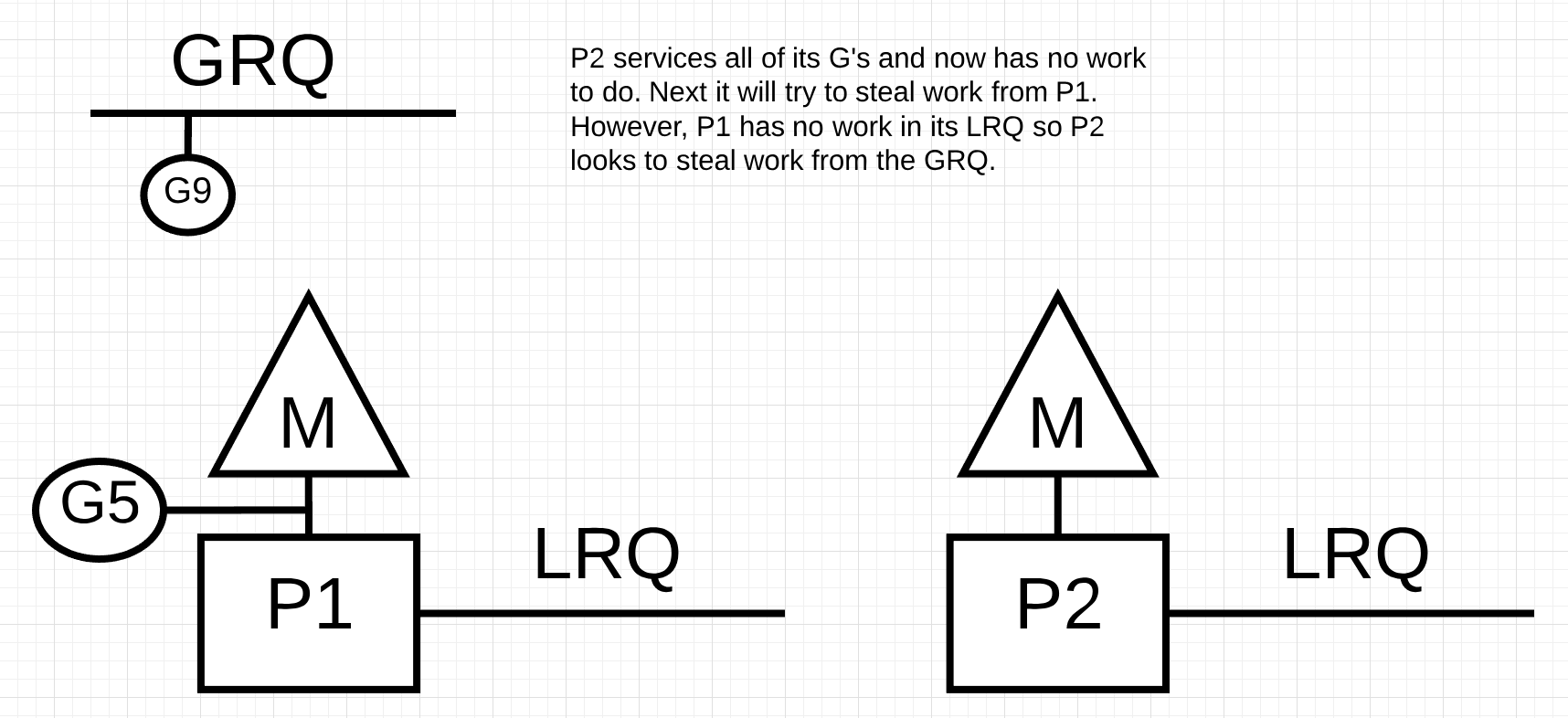

What happens if P2 finishes servicing all of its Goroutines and P1 has nothing left in its LRQ?

Figure 12

In figure 12, P2 finished all its work and now needs to steal some. First, it will look at the LRQ of P1 but it won’t find any Goroutines. Next, it will look at the GRQ. There it will find Goroutine-9.

Figure 13

In figure 13, P2 steals Goroutine-9 from the GRQ and begins to execute the work. What is great about all this work stealing is that it allows the Ms to stay busy and not go idle. This work stealing is considered internally as spinning the M. This spinning has other benefits that JBD explains well in her work-stealing blog post.

Practical Example

With the mechanics and semantics in place, I want to show you how all of this comes together to allow the Go scheduler to execute more work over time. Imagine a multi-threaded application written in C where the program is managing two OS Threads that are passing messages back and forth to each other.

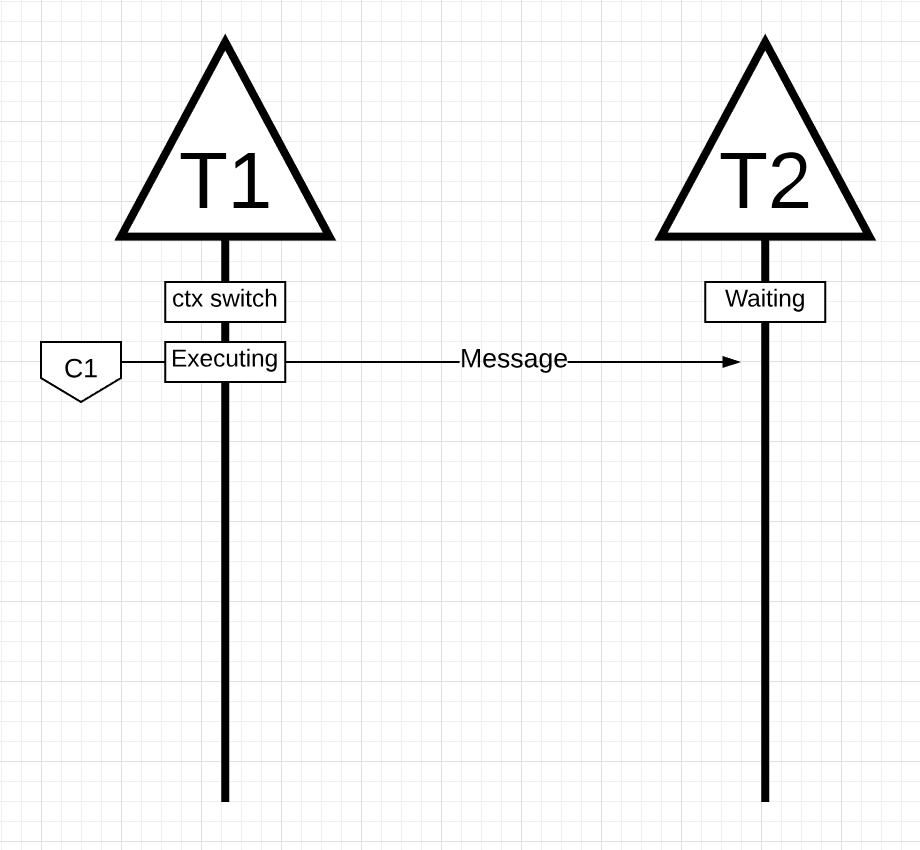

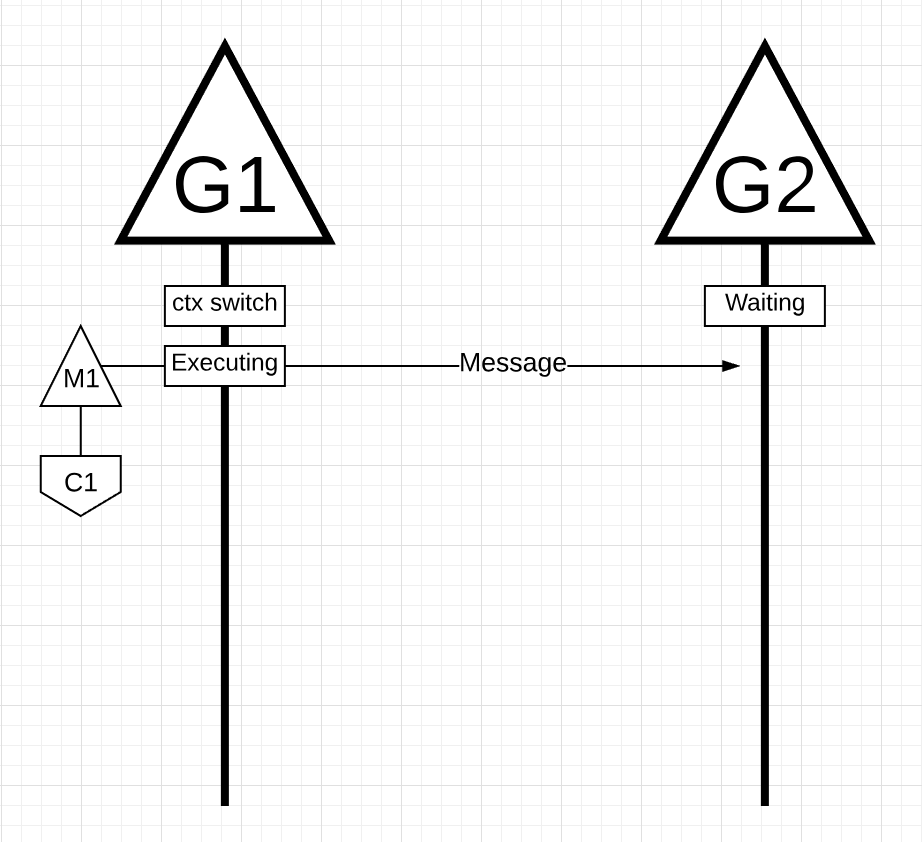

Figure 14

In figure 14, there are 2 Threads that are passing a message back and forth. Thread 1 gets context-switched on Core 1 and is now executing, which allows Thread 1 to send its message to Thread 2.

Note: How the message is being passed is unimportant. What’s important is the state of the Threads as this orchestration proceeds.

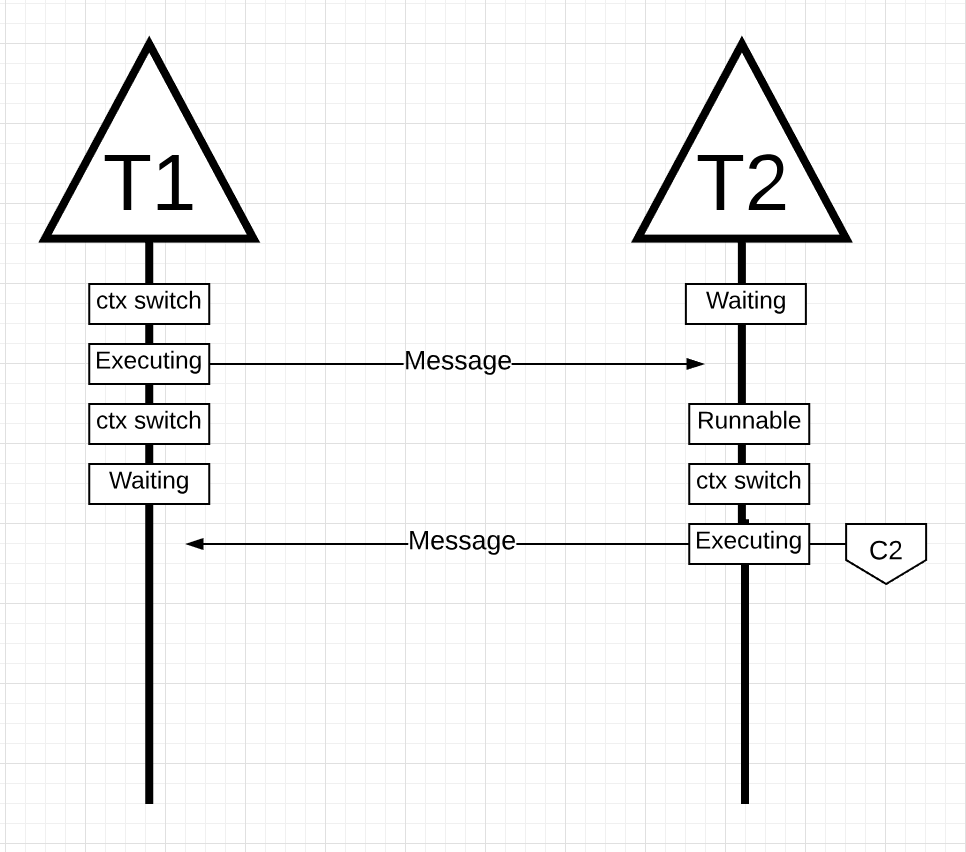

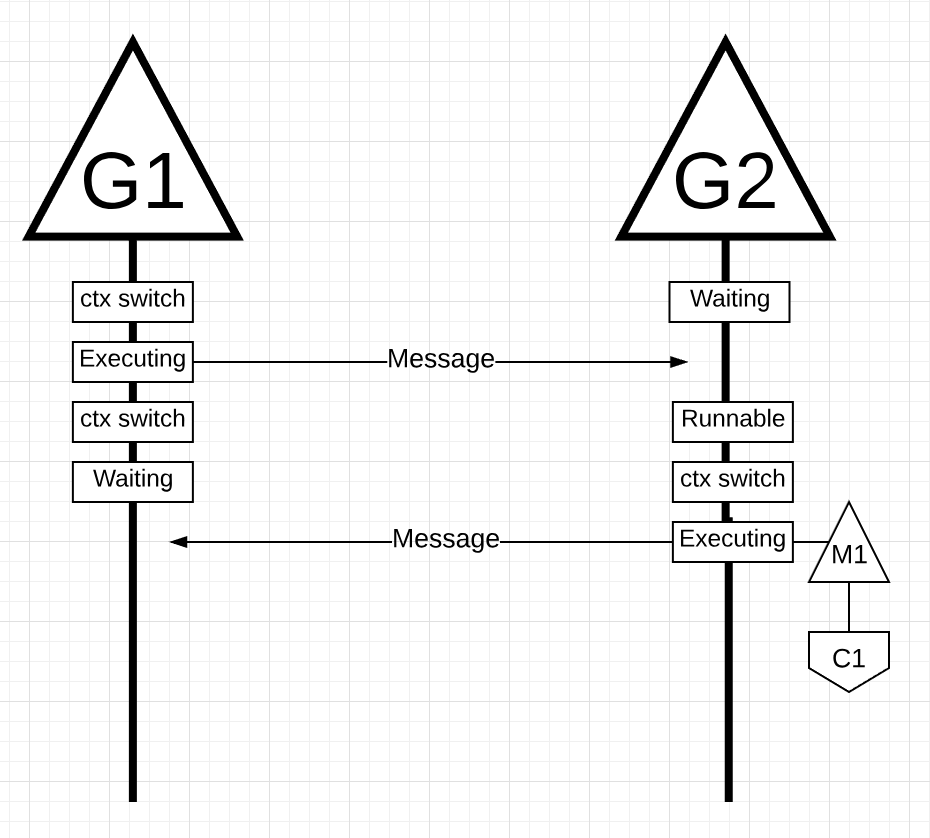

Figure 15

In figure 15, once Thread 1 finishes sending the message, it now needs to wait for the response. This will cause Thread 1 to be context-switched off Core 1 and moved into a waiting state. Once Thread 2 is notified about the message, it moves into a runnable state. Now the OS can perform a context switch and get Thread 2 executing on a Core, which it happens to be Core 2. Next, Thread 2 processes the message and sends a new message back to Thread 1.

Figure 16

In figure 16, Threads context-switch once again as the message by Thread 2 is received by Thread 1. Now Thread 2 context-switches from an executing state to a waiting state and Thread 1 context-switches from a waiting state to a runnable state and finally back to an executing state, which allows it to process and send a new message back.

All these context switches and state changes require time to be performed which limits how fast the work can get done. With each context-switching potential incurring a latency of ~1000 nanoseconds, and hopefully the hardware executing 12 instructions per nanosecond, you are looking at 12k instructions, more or less, not executing during these context switches. Since these Threads are also bouncing between different Cores, the chances of incurring additional latency due to cache-line misses are also high.

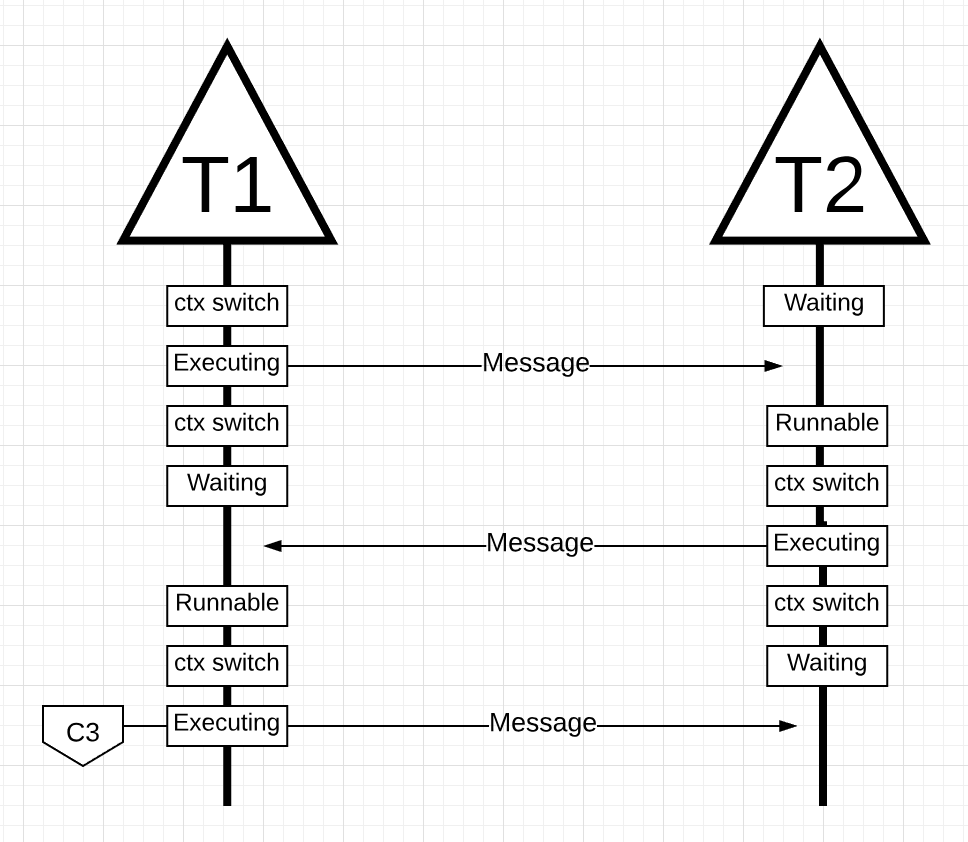

Let’s take this same example but use Goroutines and the Go scheduler instead.

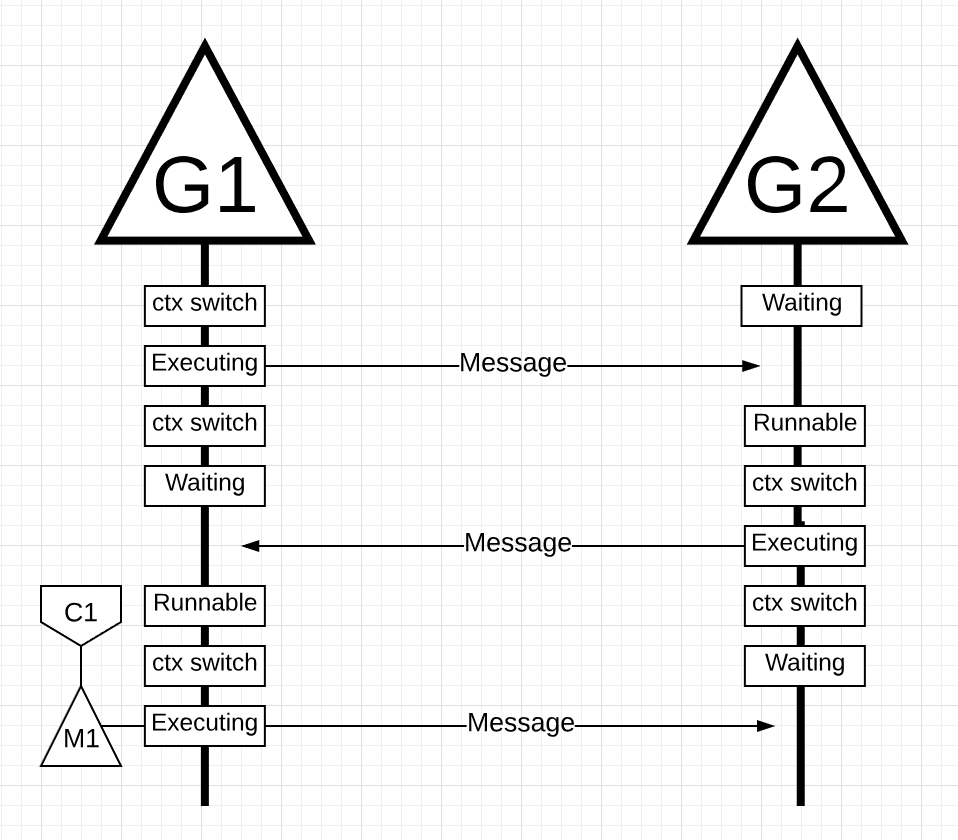

Figure 17

In figure 17, there are two Goroutines that are in orchestration with each other passing a message back and forth. G1 gets context-switched on M1, which happens to be running on Core 1, which allows G1 to be executing its work. The work is for G1 to send its message to G2.

Figure 18

In figure 18, once G1 finishes sending the message, it now needs to wait for the response. This will cause G1 to be context-switched off M1 and moved into a waiting state. Once G2 is notified about the message, it moves into a runnable state. Now the Go scheduler can perform a context switch and get G2 executing on M1, which is still running on Core 1. Next, G2 processes the message and sends a new message back to G1.

Figure 19

In figure 19, things context-switch once again as the message sent by G2 is received by G1. Now G2 context-switches from an executing state to a waiting state and G1 context-switches from a waiting state to a runnable state and finally back to an executing state, which allows it to process and send a new message back.

Things on the surface don’t appear to be any different. All the same context switches and state changes are occuring whether you use Threads or Goroutines. However, there is a major difference between using Threads and Goroutines that might not be obvious at first glance.

In the case of using Goroutines, the same OS Thread and Core is being used for all the processing. This means that, from the OS’s perspective, the OS Thread never moves into a waiting state; not once. As a result all those instructions we lost to context switches when using Threads are not lost when using Goroutines.

Essentially, Go has turned IO/Blocking work into CPU-bound work at the OS level. Since all the context switching is happening at the application level, we don’t lose the same ~12k instructions (on average) per context switch that we were losing when using Threads. In Go, those same context switches are costing you ~200 nanoseconds or ~2.4k instructions. The scheduler is also helping with gains on cache-line efficiencies and NUMA. This is why we don’t need more Threads than we have virtual cores. In Go, it’s possible to get more work done, over time, because the Go scheduler attempts to use less Threads and do more on each Thread, which helps to reduce load on the OS and the hardware.

Conclusion

The Go scheduler is really amazing in how the design takes into account the intricacies of how the OS and the hardware work. The ability to turn IO/Blocking work into CPU-bound work at the OS level is where we get a big win in leveraging more CPU capacity over time. This is why you don’t need more OS Threads than you have virtual cores. You can reasonably expect to get all of your work done (CPU and IO/Blocking bound) with just one OS Thread per virtual core. Doing so is possible for networking apps and other apps that don’t need system calls that block OS Threads.

As a developer, you still need to understand what your app is doing in terms of the kinds of work you are processing. You can’t create an unlimited number of Goroutines and expect amazing performance. Less is always more, but with the understanding of these Go-scheduler semantics, you can make better engineering decisions. In the next post, I will explore this idea of leveraging concurrency in conservative ways to gain better performance while still balancing the amount of complexity you may need to add to the code.