Remember Gary?

Pool/Getty Images

The conventional wisdom about the 2017 Trump tax cuts is that they did not work out the way Republicans promised. The White House claimed that slashing the corporate tax rate would spark a boom in business investment, eventually leading to higher wages for workers and putting thousands of extra dollars in the average family’s pocket. According to everyone from the International Monetary Fund to the Congressional Research Service, there is little evidence that those predictions have come true.

But that isn’t stopping some of the tax cuts’ architects from declaring mission accomplished. Kevin Hassett, who chaired the White House’s Council of Economic Advisers, and Gary Cohn, who helped spearhead tax reform during his time as head of Trump’s National Economic Council, have popped up in the Wall Street Journal this week with an op-ed titled, “Tax Reform Has Delivered for Workers.” It’s a valiant exercise in assembling a few true data points to paint an overall misleading picture.

The argument that cutting corporate taxes would lead to higher wages for the middle class is a multi-part bank shot. First, the thinking goes, the prospect of higher after-tax profits in the U.S. would lead companies to invest more in their businesses, by buying more software, machinery, and such. Second, this investment boom would make workers more productive, and, as a result, they’d earn more.

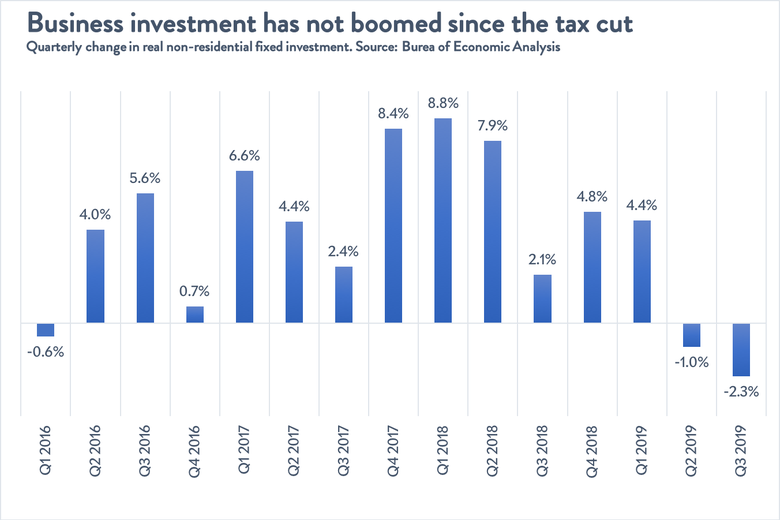

Hassett and Cohn try to argue that each of these predictions has come true. Take business investment. They point out capital spending was 4.5 percent higher in 2018 than economists had predicted it would be before the tax law passed. This is true. The IMF’s economists have pointed out the same exact thing. Based on their modeling, however, they concluded that U.S. companies likely weren’t investing because of the tax cut. Rather, companies were likely just responding to increased demand in the economy. The Trump tax cuts may have helped by putting money in people’s pockets and increasing the federal deficits, but that wasn’t the story Republicans told.

The bigger problem for Hassett and Cohn’s story is that, after that temporary pop in early 2018, business investment has cratered. For the past two quarters, it has actually been a drag on the economy.

Jordan Weissmann/Slate

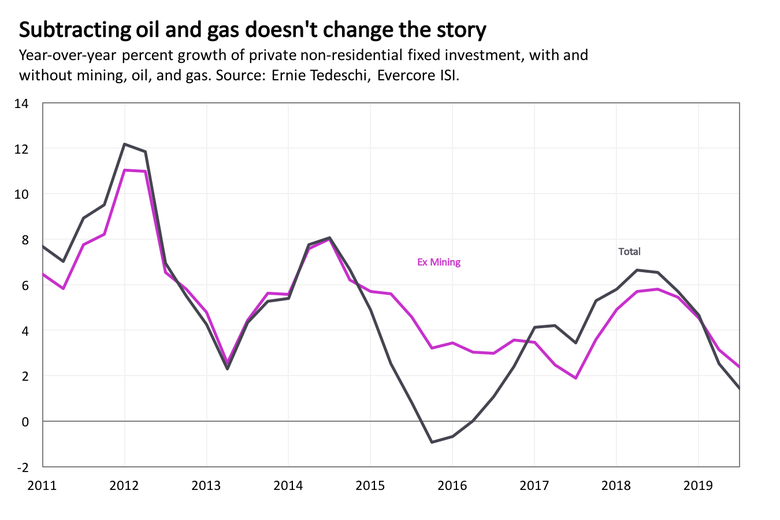

Some of the investment bust has been due to trouble in the oil and gas industry. But even if you subtract those sectors, you can see the same basic story: After a bump in early 2018, investment tails off.

Ernie Tedeschi/Evercore ISI

Investment would likely be in better shape were it not for Donald Trump’s trade war, which began to rage in earnest around the middle of 2018. This is a public relations tragedy for the tax cuts’ supporters, and an empirical challenge for economists who would like a clear sense of what the GOP’s bill actually accomplished. But in the end, all it means is that the corporate tax cuts’ benefits were small enough that they seem to have been swamped by other factors.

Having made a less-than-persuasive case that the tax cut meaningfully boosted business investment, Cohn and Hassett move on to claiming that it has already paid off for workers. In 2017, Hassett’s CEA went so far as to suggest that the average household would see its income rise by $4,000 to $9,000 within a few years due to the corporate cuts. Now, he says, things are ahead of schedule.

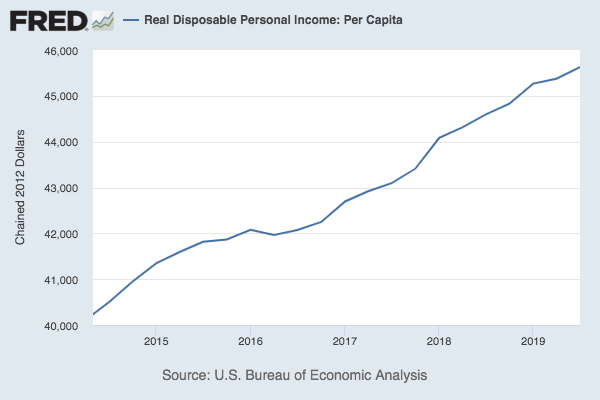

Over the past year, nominal wages for the lowest 10% of American workers jumped 7%. The growth rate for those without a high-school diploma was 9%. The median worker benefited as well, but much less so, helping to begin closing the income inequality gap. And about that $4,000? Real disposable personal income per household has increased $6,000 since the tax cuts were passed.

Wages for low-income workers have indeed been growing, but most economists would attribute that to minimum wage hikes and the gradually strengthening labor market, which has been on basically the same slow upward trajectory since the the Obama years. As for trends in disposable income, there’s not exactly a huge swerve in 2018. And again, much of the improvement is likely due to the generally hot economy created by the administration’s deficit spending.

Fred

Hassett and Cohn see this criticism coming, and try to pre-empt it. They write:

Those who say that the strong economy under President Trump is merely a continuation of past trends are in full-scale denial. Before Mr. Trump took office in January 2017, the Congressional Budget Office forecast the creation of only two million jobs by this point. The economy has in fact created seven million jobs since January 2017. At the same time, the Federal Reserve’s median forecast had the unemployment rate inching up toward 5%, almost 1.5 percentage points higher than the current 50-year low.

Again, all of these data points are true. But all they indicate is that both the CBO and Federal Reserve underestimated how much more the U.S. job market could improve before we reached full employment, something they’ve both since admitted. None of these facts tell us much about the influence of Trump’s tax cuts.

Two years in, the most honest case for the Trump tax cuts is that, if the administration hadn’t passed them, the economy might be in even worse shape due to the president’s trade war—though it’s hard to tell. For obvious reasons, the ex-administration officials defending the cuts can’t admit that, either publicly, or to themselves. They’re bound to keep doing victory laps, no matter how unconvincing their case might be.