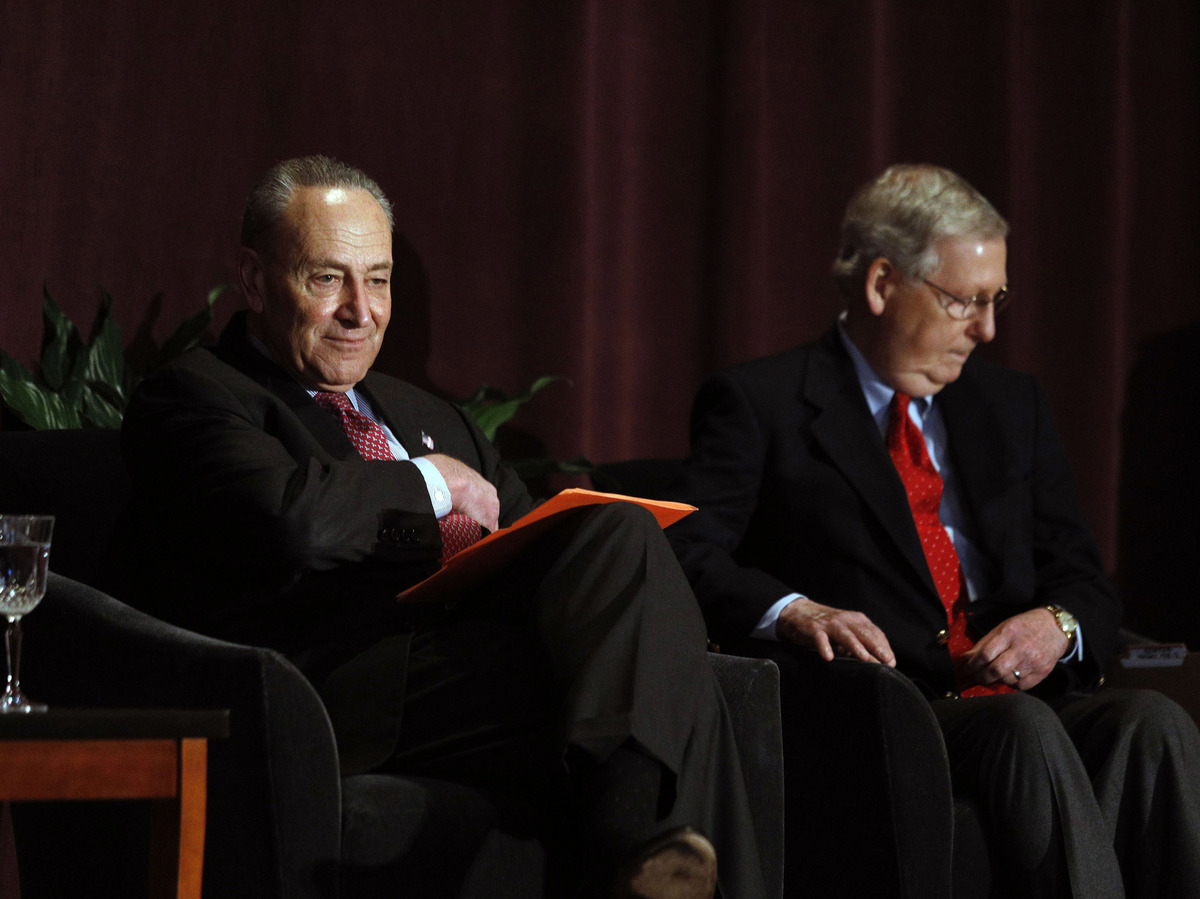

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, right, and Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer wait on stage together at the University of Louisville's McConnell Center before Schumer's scheduled speech last year. Bill Pugliano/Getty Images hide caption

toggle caption

Bill Pugliano/Getty Images

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, right, and Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer wait on stage together at the University of Louisville's McConnell Center before Schumer's scheduled speech last year.

Bill Pugliano/Getty Images

With the House impeachment of President Trump, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., says it's now up to the Senate to adjudicate the matter. "We're ready to sit there and have the trial the Constitution requires," McConnell told Fox News on Monday.

But there's still no date set for such a trial, and McConnell is blaming House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., who has yet to forward to the Senate the two articles of impeachment.

"We're at an impasse," McConnell declared on "Fox and Friends," reported to be Trump's favorite TV show. "We can't do anything until the Speaker sends the papers over, so everybody — enjoy the holidays."

Pelosi, for her part, contends it's the Senate that's holding things up. "We cannot name managers until we see what the process is on the Senate side," she declared minutes after the House impeachment votes, in declining to appoint the House members who'd make the case in the Senate for Trump's removal from office. "So far we haven't seen anything that looks fair to us."

Central to this stalemate is whether some Trump administration officials who declined to testify in the House impeachment inquiry should be obliged to appear as witnesses in a Senate trial.

Senate Minority leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., sent McConnell a letter last week requesting four such witnesses: acting White House chief of staff Mick Mulvaney, former National Security Adviser John Bolton, Office of Management and Budget official Michael Duffey, and top Mulvaney adviser Robert Blair. Schumer also demanded Trump administration documents for the Senate trial that were withheld from the House.

"I haven't seen a single good argument about why these witnesses shouldn't testify or these documents be produced," Schumer told reporters last week, "unless the president has something to hide and his supporters want that information hidden."

McConnell insists he remains open to new testimony in a Senate trial. "We haven't ruled out witnesses," he told Fox News on Monday. "We've said let's handle this case just like we did with President Clinton - fair is fair."

The Senate's top Republican pointed out that when Clinton went on trial in the Senate in 1999, the Senate - which included a newly sworn-in Chuck Schumer, who'd voted weeks earlier in the House against impeaching Clinton — voted unanimously for a procedure "to go through the opening arguments, to have a written question period, and then, based upon that, deciding what witnesses to call."

But for both McConnell and Schumer, statements they made at the time of Clinton's 1999 Senate trial are, in fact, nearly the opposite of what each of them is saying now.

It was McConnell who argued on CNN after Clinton's impeachment in the House and before his Senate trial that the proceeding should include at least three fact witnesses. "Every other impeachment has had witnesses," McConnell said then. "It's not unusual to have witnesses in a trial."

And it was Schumer who, three days after Clinton's Senate trial began, contended on NBC's "Meet the Press" that further testimony was unnecessary. "I do not think we need witnesses," he said, "because we have studied this for a year."

In his final floor speech in the House on the day before that GOP-run chamber voted to impeach Clinton, Schumer sounded a dark warning. "I expect history will show that we've lowered the bar on impeachment so much, we have broken the seal on this extreme penalty so cavalierly, that it will be used as a routine tool to fight political battles," the outgoing congressman and senator-elect from New York intoned. "My fear is that when a Republican wins the White House, Democrats will demand payback."

McConnell expressed no such qualms about removing a Democratic president for having allegedly lied about an extra-marital affair. "I submit to my colleagues that if we have no truth and we have no justice, then we have no nation of laws," he told fellow senators behind closed doors on Feb. 12, 1999, the day Clinton was acquitted. "No public official, no president, no man or no woman is important enough to sacrifice the founding principles of our legal system."

With the proverbial shoe now on the other foot as a Republican president faces a Senate trial, McConnell is sounding an alarm much like Schumer's warnings 21 years ago. "If the Senate blesses this slapdash impeachment, if we say that from now on this is enough, then we invite an endless parade of impeachable trials," McConnell warned on the Senate floor the morning after the House impeached Trump. "Future Houses of either party will feel free to toss up a jump ball every time they feel angry, free to swamp the Senate with trial after trial, no matter how baseless the charges. We would be giving future Houses of either party unbelievable new power to paralyze the Senate at their whim."

And Schumer is no longer cautioning about the perils posed by impeachment for both parties. "The president has offered nothing exculpatory to disprove the evidence that has been put forward," the Senate's Democratic leader said of Trump last week. "Instead, he's orchestrated a cover-up. It's left many in the Senate and millions across the country asking, what is the president hiding? Why doesn't he want the facts to come out?

Schumer has not acknowledged any inconsistency between his stands on the Senate trial of Clinton and the expected adjudication of Trump, despite having gone from opposing fact witness testimony to demanding it.

"The witnesses in '99 had already given grand jury testimony — we knew what they were going to say," Schumer said last week of Clinton's trial. "The four witnesses we've called have not been heard from."

For McConnell, the apparent about-faces both he and Schumer have made on impeachment should come as no surprise.

"I think it's pretty safe to say, in a partisan exercise like this, people sort of sign up with their own side," he told reporters last week. "And what we may have felt 20 years ago may not be the same as today."

The Jan. 7 start for a Senate trial that Schumer proposed in a letter to McConnell is the same day of the same month that Clinton's trial began. Whether it does begin on that date or, for that matter, begins at all, depends on breaking the witness testimony stalemate. For that, the two Senate leaders will have to agree on a way forward that Speaker Pelosi considers fair enough to send the Senate the articles of impeachment and designate the trial's House managers.