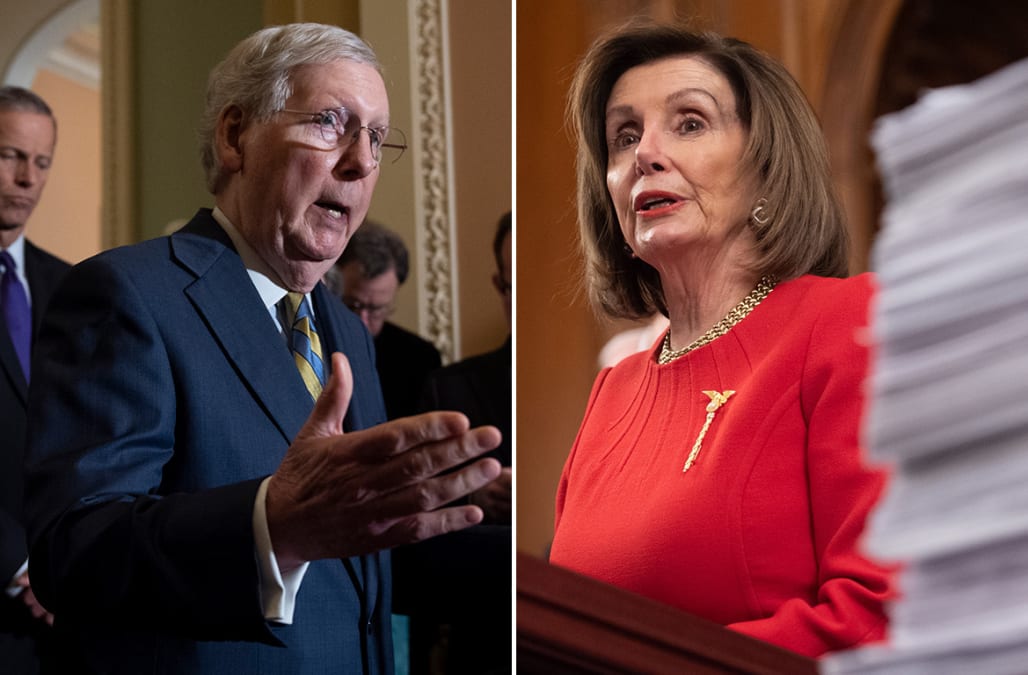

WASHINGTON — The fate of the Trump impeachment — in fact, the fate of the entire Trump presidency — now rests on the outcome of a battle between the two ablest political generals in recent American history: House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky.

They are struggling over a few sheets of paper that, when stapled together, barely rival a standard apartment lease in heft. These are the articles of impeachment — one charging abuse of power, the other obstruction of Congress — approved by the House of Representatives on Wednesday, in a step that had been taken only twice before in American history.

These articles are now supposed to be transmitted to the Senate for a trial that could lead to Trump’s acquittal, or his removal from office. But that trial cannot begin until Pelosi names impeachment managers — in effect, prosecutors — to transmit those articles to the Senate.

Wednesday’s vote had not been a surprise. What followed was: a press conference in which Pelosi announced she would not send the articles of impeachment until McConnell made certain assurances about the procedures the Senate would follow. Democrats know that the Republican majority in that chamber is sure to acquit Trump, whatever rules are adopted for the trial. All the same, they don’t want the trial to amount to a farce.

McConnell promptly accused Pelosi of “hemming and hawing” in one tweet. Another tweet from the morning after impeachment taunted Democrats, accusing them of getting “cold feet” about their case against Trump.

While revealing little about how long the delay would last, Pelosi indicated, as she has several times since the impeachment vote, that she is not rattled by such attacks.

“I don’t care what the Republicans say,” she told journalists during her weekly press conference on Thursday.

In effect, an outright confrontation between Pelosi and McConnell became inevitable when she was named speaker after Democrats retook the House in the 2018 midterm congressional elections. Since then, McConnell has refused to take up a number of Democratic bills passed by the House, including measures on gun control, voting rights and transgender protections. He has gleefully owned the nickname of “the Grim Reaper” for his approach to Democratic legislation.

Yet much as Democrats dislike McConnell, they’ve had few means to challenge him directly.

Until now.

No confrontation over legislation is as complex or consequential as that over presidential impeachment. It is especially so because the House brings the articles of impeachment to the Senate and argues its case there. Rarely, if ever, are the two chambers so extensively — and publicly — enmeshed in each other’s affairs.

And in a sense, Pelosi and McConnell are the perfect leaders for these supremely strange and significant times. Both are exceedingly gifted tacticians who can maintain their equipoise even in the most tense moments. Both keep firm control over their caucuses.

Both have also been here before, more than once. Pelosi was speaker during the 2008 financial crisis, which was taking place in the midst of a presidential race. A bank bailout was necessary, but also unpopular with many Democrats. At one point, Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson actually got down on bended knee to beg Pelosi to marshal the votes necessary to save the financial system from what many feared would be a complete collapse. She failed at first, but eventually mustered enough votes to pass a bipartisan $700 billion bailout.

Pelosi is “best at one of the most critical, if not most critical, roles of speaker, which is to court votes and count votes,” Brookings Institution fellow Elaine Kamarck wrote in 2018, adding that Pelosi was especially adept at “understanding the political challenges of each and every member of Congress and then devising a legislative package that can pass.”

Another key victory for Pelosi was the passage of the Affordable Care Act under President Barack Obama. At points, the complexity and seeming unpopularity of the health care bill seemed to doom its prospects, but once again Pelosi patiently and diligently scrounged for the necessary votes, working the halls of Congress after the fashion of legendary leaders like Sam Rayburn or Tip O’Neill.

“As an act of legislative prowess, her revival of [the Affordable Care Act] remains a signature accomplishment,” Ryan Grim recently wrote in the Intercept, a progressive publication that tends to be critical of mainstream Democrats like Pelosi.

If Democrats are generally in awe of the House speaker, conservatives feel the same way about the man who sells “Cocaine Mitch” T-shirts on his website (the joking reference is to a slur by a failed Senate candidate from neighboring West Virginia). “He’s a master of Senate rules and procedure, he’s politically savvy and he’s tough as nails,” says Mike Davis, a conservative operative whose organization, the Article III Project, has worked on judicial nominations with Senate Republicans.

Davis predicted that McConnell would “eat Pelosi's lunch in a congressional feud over impeachment.”

McConnell’s most consequential decision in recent years has been to refuse to take up the nomination of Merrick Garland to the Supreme Court in the final year of the Obama administration, leaving the seat open for Trump to fill. The open seat became a rallying cry for conservatives during the 2016 campaign.

The Garland fight was the capstone of a years-long effort by McConnell to remake the federal judiciary. His “historic judge blockade” during the Obama presidency, as Politico deemed it, left dozens of vacancies on the federal bench. These have since been filled by Trump nominees.

And it was McConnell’s steadfastness that rescued the Supreme Court confirmation of Brett Kavanaugh, which had been imperiled by allegations of sexual misconduct. Other Republicans began to waver, fearing popular backlash. McConnell did not.

“I’m stronger than mule piss,” he said of his own resolve.

And if McConnell wants legislation to die, the death is all but certain. For example, an election security bill co-sponsored by Sen. James Lankford, R-Okla., and Sen. Amy Klobuchar, D-Minn., seemed destined for easy passage in the Senate. But at the urging of the White House — whose legal counsel at the time, Don McGahn, is a close McConnell ally — the Senate majority leader prevailed on Rules Committee Chairman Roy Blunt, R-Mo., and the bill was promptly dispatched to the legislative graveyard.

Having waged plenty of proxy battles, Pelosi and McConnell now face each other directly on impeachment, which dwarfs every previous confrontation.

Pelosi, for her part, has been circumspect in her statements, saying that she does want to have a Senate trial, but that absent certain provisions, including seeking testimony and documents from administration witnesses, the trial would be a disservice to the Constitution. She has allowed legal scholars to make the argument that the House can unilaterally hold back the articles from the Senate.

Not all legal scholars agree that the tactic is permissible — or wise. Noah Feldman, a Harvard law professor who testified as a Democratic witness during the impeachment inquiry, argued in a widely shared Bloomberg op-ed that if Pelosi fails to transmit the articles, she will have effectively aborted the entire impeachment process, thus allowing Trump to declare himself acquitted.

McConnell may have committed a rare misstep when he seemed to admit that he had little interest in hearing the evidence the House has gathered against Trump. “I’m not impartial about this at all,” he said the day before Trump was impeached. Several days before that, he had informed Sean Hannity of Fox News that there was “total coordination” between him and the White House counsel on a framework for the trial.

These admissions have provided Pelosi and fellow Democrats with grounds for arguing that McConnell is not interested in holding a fair trial and that they are justified in holding back the articles until he makes what they deem to be necessary concessions.

The Democratic delay tactics have infuriated McConnell, though they are not all that different from how he has often maneuvered in the Senate. The morning after the impeachment vote, he raged against Democrats on the Senate floor, accusing them of conducting a “shoddy” impeachment inquiry, the results of which they now feared, he surmised, to put in the Senate’s hands.

Pelosi does not appear to have been rattled. Speaking to Politico on Thursday, she said she was “never afraid” and “rarely surprised.”

More from Yahoo News:

Congress passes bill raising minimum tobacco and vape smoking age to 21

Pelosi's risky strategy to withhold impeachment from Senate roils Washington

Trump praises N.J. Democrat who is switching parties to vote against impeachment