04:11 pm | 25. September 2019

As waves of online nationalism in China continue to strike European businesses, it's a good time to become more familiar with the dynamics behind this phenomenon.

European luxury brands had a difficult summer in China. In quick succession, like models strutting the catwalk, leading fashion houses from Paris to Milan faced a chorus of criticism from Chinese internet users for perceived slights against the country’s dignity and national sovereignty.

On August 11, Italian fashion brand Versace faced online outrage for a t-shirt that appeared to identify Hong Kong as its own country. The brand's artistic director, Donatella Versace, posted to Instagram to say she “wanted to personally apologize for such inaccuracy and for any distress that it might have caused."

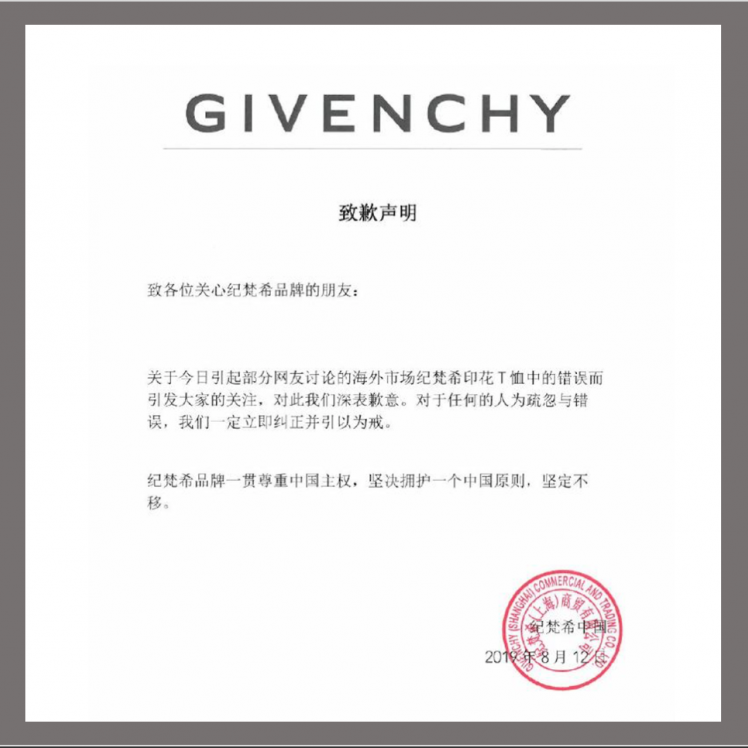

In an apology in Chinese posted to Weibo, Givenchy "deeply apologizes" on August 12, 2019, and says it upholds the one China principle.

The next day scandal struck the French luxury brand Givenchy for a similarly designed top. The brand was pressed to apologize on Chinese social media, saying it “resolutely upholds the one China principle, without reservation.” Right on cue, the Austrian jewelry company Swarovski was buffeted by its own Chinese scandal on August 13, after Chinese internet users exposed it for listing Hong Kong as a separate country on its website. The company issued a public mea culpa, saying that it “sincerely apologizes to the people of China" for its "misleading communication on China’s National Sovereignty."

In fact, sovereignty related scandals originating in Chinese cyberspace have reached far beyond fashion, far beyond Europe, and into just about every industry imaginable. In Asia, dozens of food and beverage brands, accused by Chinese internet users of tacitly supporting Hong Kong and Taiwan independence, were cornered into issuing statements affirming their support for “one country, two systems.”

Hong Kong’s flagship airline Cathay Pacific was targeted with a boycott by Chinese netizens for its alleged support for the Hong Kong protests. Meanwhile, Finland’s largest airline Finnair, wary of online outrage from mainland Chinese, warned its flight attendants in Hong Kong to stay away from the protests. Even a small bubble tea shop based in the German city of Düsseldorf was subjected to a wave of online harassment after its manager posted a message to Instagram — a service censored from within China — suggesting Taiwan and China are “separate nations.”

These successive waves of Chinese cyber-nationalism are not an entirely new phenomenon. For several years now, at least since 2016, nationalistic netizens have fervently criticized and harassed politicians, celebrities, and companies that have allegedly supported pro-independence movements.

How should we understand the phenomenon of cyber-nationalism? What does it tell us about China and its impact on Europe and the world?

In January 2016, when Tsai Ing-wen of the independence-leaning Democratic Progressive Party was elected Taiwan’s President, thousands of so-called “online crusaders” flooded Tsai’s Facebook page with trolling messages — the first time the world witnessed a major online activism operation by Chinese nationalists.

How should we understand the phenomenon of cyber-nationalism? What does it tell us about China and its impact on Europe and the world? On the question of agency, are these actions spontaneous outpourings of nationalism – or are they being pushed by the Chinese Communist Party?

In this article I discuss the facts as we presently know them – as well as those things we’re really not sure of – on the basis of previous academic research on the topic.

How Nationalistic Are Chinese Netizens?

It is notoriously difficult to conduct independent public opinion polls in China, especially on topics such as nationalism that are deemed “politically sensitive”(政治敏感). Still, there are some valuable data, albeit sparse, that could shed some lights on the nationalistic tendencies of Chinese netizens.

The general impression about nationalistic netizens is that they are young and proficient in digital technologies. If this is true, one way to assess cyber-nationalism in China is to see whether young people more nationalistic than the older generations. With this approach in mind, Harvard professor Alastair Iain Johnston analyzed a set of surveys conducted in Beijing from 2007 to 2015, and reached the conclusion that “younger respondents are less nationalistic than older ones.” For example, in 2015, only about 25 percent of those in the “post-80s” and “post-90s” generations – roughly between 15 and 30 years old at the time of the study – strongly agreed with the statement “I prefer to be a Chinese citizen.” Meanwhile, 40 percent of the older generations strongly agreed with the statement. More than 30 percent of the “post-80s” and “post-90s” generations strongly disagreed with the statement “Support your country even when it is wrong,” while just 15 percent of respondents in previous generations strongly opposed it.

This finding contradicts the conventional view that the “Patriotic Education Campaign,” which was launched in the early 1990s, boosted nationalism among the youngsters.

Despite weaker nationalistic tendencies, young people and netizens are found to be more hawkish in terms of foreign policy beliefs and attitudes. According to Cornell professor Jessica Chen Weiss, about half of the netizens surveyed in a 2015-16 study felt that China relied too little on its military strength to achieve its foreign policy goals, whereas less than 40 percent of the general population held the same opinion. This suggested that netizens might be more hawkish than non-netizens. Young people were also found to be more supportive of hardline foreign policies, fitting into the image of “angry youth” activists.

Aside from surveys, scholars also analyzed social media discussions on foreign relations to see if these could be characterized as nationalistic. Examining 6,000 posts on topics such as “Taiwan” and “Diaoyu Islands” by 146 opinion leaders on Weibo, a research project found that “the dominant voice tends to be anti-regime” rather than nationalistic. It should be noted that the Weibo data was collected in 2013, before the crackdown on liberal intellectuals. It is very likely that the dominant discourse on Weibo is now less critical and more nationalistic.

In short, there is no evidence suggesting that Chinese netizens are more nationalistic than the general public, but survey data does show that they are more hawkish in their foreign policy preferences than the general public. In 2013, the year the Weibo data was collected, opinion leaders on Chinese social media tended to be more liberal-minded than nationalistic. Changes under the leadership of Xi Jinping since that time have been rather substantial, and so new data could reflect something different.

Is Nationalism On the Rise in China?

The aforementioned Harvard professor, Alastair Iain Johnston, conducted a quick search in a database of English-language news media and found that the word “rising” was very frequently placed before the term “Chinese nationalism.” This reflected, he wrote, a common perception and fear among Western observers.

However, Johnston’s analysis of survey data ranging from 2002 to 2015 suggested that this idea of “rising Chinese nationalism” might in fact be a myth. Use of this sense of “rising” nationalism peaked in the media in 2009, following an exciting yet turbulent 2008 packed with major events such as the Beijing Olympics, and incidents such as unrest in Tibet and the global financial crisis. According to survey data, the level of nationalism in China has dropped since then. In 2009, for example, more than 60 percent of respondents in one survey strongly agreed that “China is a better country than most,” but by 2015 that number had declined to around 30 percent.

One might speculate that a reversal of that decline could be reflected in surveys covering the past two years, corresponding to more potent nationalist language during Xi Jinping’s second term as well as the US-China trade war and Hong Kong protests in 2019. So far, however, we do not have these survey results.

China’s censorship system further complicates the issue by suppressing critical voices. We should be very careful in inferring the state of Chinese nationalism from a few prominent cases.

The recurrence of social media “crusades” and boycotts since 2016, noted at the outset, seems to provide some evidence for “rising nationalism,” but it is worth noting that social media tend to amplify more radical voices, drowning out voices in the middle. China’s censorship system further complicates the issue by suppressing critical voices. We should be very careful in inferring the state of Chinese nationalism from a few prominent cases.

Does the Party-State Directly Support Online Nationalism?

Largely due to opacity and lack of transparency in Chinese politics, some outside observers tend to perpetuate conspiracy theories about cyber-nationalism. One such theory is that these apparently voluntary and spontaneous actions have actually been organized in secret by the Chinese Communist Party.

However, we should note, as many China experts have, that collective action, whether online or offline, is not something the party-state generally welcomes, whatever the agenda. Such activities are simply too dangerous for the risk-averse state, as movements can easily go awry and transform into anti-government protests, undermining stability. Activism around nationalistic convictions is particularly dangerous, as netizens could turn against the party-state if they see government actions as failing to fulfill nationalistic hopes.

One recent example during the Hong Kong protests occurred after Chief Executive Carrie Lam announced the formal withdrawal of the extradition bill. By this point, nationalistic memes and discussions had proliferated on Chinese social media for several weeks, and many mainland Chinese online expressed disappointment, disapproval and anger with this apparent capitulation by Lam. Taking to the Weibo platform, many netizens accused the government of being too soft on the Hong Kong protesters.

Therefore, a more likely approach for the party-state is to tacitly endorse and carefully control nationalistic activism rather than fully supporting or even organizing such movements. My previous study on the 2016 Facebook crusade against Tsai Ing-wen indicated that the movement was organized in a bottom-up fashion, and the party-state only stepped in when they considered it a good time to take advantage of the movement to boost regime legitimacy.

Who Is Promoting Online Nationalism in China?

Another caution as we look at cyber-nationalism in China is to avoid the assumption that there is only a single, uniform party-state actor. The situation is often far more complex. While the party-state as a whole is likely to show a relatively measured attitude towards nationalistic activism, some official organizations or groups may be more invested in promoting such sentiment among the public, especially the younger generation.

The Communist Youth League (CYL) is one major organization that actively pushes the nationalism agenda. A few years ago, the CYL was faced with deep challenges both in terms of its declining organizational function within the Party, and in light of criticism from senior leaders. In order to rebuild its legitimacy and status within the party, the CYL seized the opportunity to promote nationalism on digital media platforms, with products principally targeting young people. It is not surprising, then, that the CYL was the first to endorse the social media crusade against Hong Kong protesters.

Official media including the People’s Daily, Xinhua News Agency, and CCTV are also active in promoting nationalism on social media. A few years ago, I interviewed several social media editors at official media organizations. They told me that they were under pressure to attract more followers, page views, and likes on Weibo and WeChat. When they found that nationalistic posts were most likely to draw massive attention and perform well in terms of engagement metrics, they routinely posted such content. In other words, promoting online nationalism can be a strategy for official media to gain influence online and fulfill the official mission of “occupying the online public opinion field” (占领网络舆论阵地).

Commercializing Nationalism

In addition to official media, there is a large group of social media accounts managed by private start-up companies – the so-called “self-media,” or zimeiti (自媒体) — that participate actively in online nationalism campaigns. For example, College Daily, a start-up account with millions of followers on WeChat and several rounds of venture capital investment, regularly publishes highly nationalistic content, some of which was found to have been fabricated.

Companies like College Daily most likely follow the official Party narrative in order to remain politically safe and protect their commercial interests. After all, nationalistic content has the potential to bring in more followers and more advertising revenue. The commercial side of nationalism is often ignored but actually plays a vital part in the social media environment.

In an era of anti-globalization, strongman politics, and echo chambers enabled by social media platforms, the “rise” of cyber-nationalism in China (if this is supported as fact by empirical studies) is not an unexpected outcome. But the development of nationalistic trends and tendencies is a complicated process influenced by numerous internal (psychological) and external (social) factors, local and global contexts, as well as commercial, cultural, and of course political forces.

For policy makers and businesses in Europe concerned with China’s cyber-nationalism, there are many issues that deserve careful consideration as Europeans seek to maintain mutual understanding and cooperation while upholding their own values. For example, how can and should companies respond — and how much contrition, if any, is really necessary — when cyber-nationalist criticisms target language on online platforms outside China that has a right to exist in open societies? Think, for example, of the 2018 case in which the Mercedes-Benz brand faced a backlash in China over an Instagram post using a rather innocent quote from the Dalai Lama. In that case, Daimler apologized unreservedly, even with a formal letter to China's ambassador to Germany, saying that it would try to enhance its "understanding of China’s culture and values." Such acts are bound to make citizens and consumers in Europe ask: What of our values?

But rather than grasping cyber-nationalism in China through simplistic frames, we should consider the context and nuance behind cases of online outrage like those that buffeted European brands this summer. The last thing policy makers and businesses should do is to exaggerate China’s nationalism and feed into the sentiment of antagonism and hostility. A smarter approach is to learn more about Chinese people’s emotions and strategically cultivate an environment for mutual understanding and cooperation, maintaining at the same time a firm stance on their own values. In fact, Chinese people have a deep fear and disdain for isolationism (闭关锁国). They wish their country to be respected by other nations — a goal that has to be achieved through truly mutual understanding and cooperation.