In my work as a journalist I am lucky enough to meet some brilliant people and learn about exciting advances in technology - along with a few duds.

But every now and then I come across something that resonates in a deeply personal way.

So it was in October 2018, when I visited a company called Medopad, based high up in London's Millbank Tower.

This medical technology firm was working with the Chinese tech giant Tencent on a project to use artificial intelligence to diagnose Parkinson's Disease.

This degenerative condition affects something like 10 million people worldwide. It has a whole range of symptoms and is pretty difficult to diagnose and then monitor as it progresses.

Medopad's work involves monitoring patients via a smartphone app and wearable devices. It then uses a machine learning system to spot patterns in the data rather than trying to identify them by human analysis.

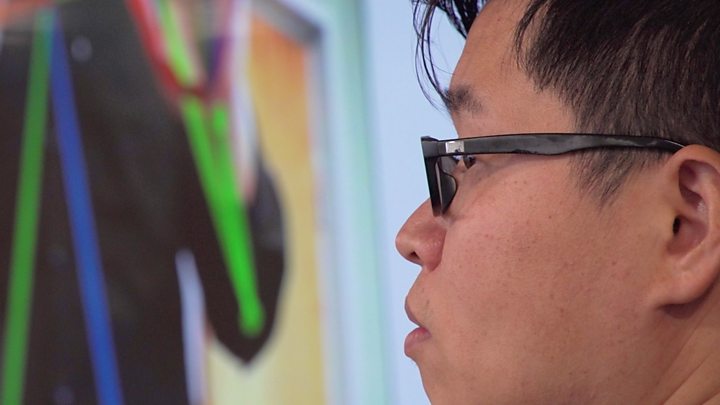

In its offices we found one of its staff being filmed as he rapidly opened and closed his fingers - stiffness in these kind of movements is one of the symptoms of Parkinson's.

As we filmed him being filmed, I stood there wondering whether I should step in front of the camera and try the same exercise.

Media playback is unsupported on your device

For some months, I had been dragging my right foot as I walked and experiencing a slight tremor in my right hand.

Getting to grips

I had first dismissed this as just part of getting older, but had eventually gone to see my GP.

She had referred me to a consultant neurologist, but at the time of filming I was still waiting for my appointment.

As we left Medopad, I clenched and unclenched my fingers in the lift and reflected on what I had seen. A few days later my coverage of the project appeared on the BBC website.

Three months on, in January this year, I finally met the consultant.

She confirmed what I had long suspected - I was probably suffering from idiopathic Parkinson's Disease. The "idiopathic" means the cause is unknown.

As I got to grips with the condition and started a course of medication, I quickly found out that there are all sorts of unknowns for people with Parkinson's.

Why did I get it? How quickly will the various symptoms develop? What are the hopes of a cure?

There are no reliable answers.

My response has been to take a great interest in how the technology and pharmaceutical industries are investigating the condition.

Developments in artificial intelligence, coupled with the availability of smartphones, are opening up new possibilities, and this week I returned to Medopad to see how far it had progressed.

Media playback is unsupported on your device

I asked the firm's chief executive, Dan Vahdat, whether he had noticed anything that suggested I might have a special interest in Parkinson's when I first visited.

"I don't think we noticed anything specifically," he said.

"But - and that's weird for me to tell you this - I had this intuition that I wanted to get you to do the test."

That, of course, did not happen but over the last year there has been a clinical trial involving London's King's College Hospital.

People with Parkinson's have been given a smartphone app, which their relatives use to record not just that hand-clenching exercise but other aspects of the way they move.

"We think this technology can help to quantify the disease," Dan explained.

No instant impact

"And if you can quantify the disease, it means you can see how the disease progresses.

"It gives you lots of opportunities, in terms of treatment adjustments, interventions at the right time, potentially screening a larger cohort of patients with the technology in ways that were not possible before."

This made me think about my own situation.

Since February, I have been prescribed Sinemet - one of the most common Parkinson's drugs - in the form of two tablets taken three times a day.

While some patients see an instant impact, I cannot say I notice much effect.

If anything my main symptom, dragging my right foot, has got slightly worse. When I see my consultant every four months we discuss whether the prescription should be adjusted, but it is difficult for me to quantify my symptoms.

Dan told me this was exactly the kind of scenario they are trying to address.

"We think you will end up having a more continuous observation via machine and the doctors can look at it remotely. And with that they will be able to adjust your treatment, if needed, because potentially right now you're either overdosing or underdosing."

I am now going to get access to the trial app and look forward to finding out what it says about me.

This is just one of many projects run by a variety of companies where real-time data is collected from people with Parkinson's and other conditions via their handsets.

The search for a cure to Parkinson's goes on. We appear to be a long way off, but in the meantime quantifying a condition like mine could do a lot to improve how I and many others cope with the symptoms.

What is exciting to me is that the smartphone revolution, which I have documented since watching Steve Jobs unveil the iPhone in 2007, now promises to change healthcare just as it has transformed many other aspects of our lives.

And I hope to continue reporting on that revolution for many more years.