Let’s see if this sounds familiar: You churn through the day at work under deadline pressure, racing to meetings, dashing off emails, feeling busy, purposeful and a little breathless. Yet as the end of the traditional workday draws near, you realise with a sinking feeling that you haven’t even begun the big project you meant to tackle that day.

So you bring work home, or decide not to and can’t stop feeling guilty about it. Either way, your work is spilling over into the rest of your life, stealing time and mental bandwidth away from family or rest or fun, and leaving you feeling exhausted and a little resentful. You resolve that tomorrow will be different. But come morning, you inevitably find yourself back on the treadmill of busyness.

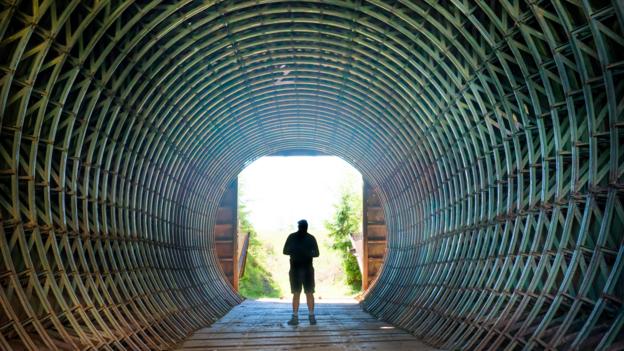

That’s a pattern Antonia Violante has seen a lot at workplaces she’s been studying in the United States for a project on work-life balance. Behavioural scientists and researchers like her call it “tunnelling”. When we’re stressed and feeling pressed for time, Violante explains, our attention and cognitive bandwidth narrow as if we’re in a tunnel. It can sometimes be a good thing, helping us hyper-focus on our most important work.

But tunnelling has a dark side. When we get caught up in a time scarcity trap of busyness, a panicked firefighting mode, we might only have the capacity to focus on the most immediate, often low-value tasks right in front of us rather than the big project or the long-range strategic thinking that would help keep us out of the tunnel in the first place. “We see people end up tunnelling on the wrong thing,” she says.

Why email offers false rewards

Email certainly falls under that category. To Violante, a senior associate at ideas42, a non-profit firm with offices across the US and in New Delhi that uses behavioural science to solve real-world problems, email is the perfect addictive “attention slot machine”. Our brains are wired for novelty, so we actually love being interrupted with every random ping and ding of a new message. And humans enjoy feeling busy and productive. Combine time scarcity with that pull of novelty and our busyness craving and it’s easy to see how we end up focusing our time and attention on whatever’s right in front of us, which, these days, is email.

Email pings feed our brains’ craving for busyness, like an “attention slot machine”, causing us to tunnel on unimportant, menial tasks (Credit: Getty Images)

Busy-loving humans have such an aversion to idleness, in fact, that one study found people preferred giving themselves electric shocks rather than have nothing to do. “So it’s easy to be swept up trying to keep on top of your email inbox,” Violante says. “It allows us to be busy, which feels good. But it leads to a false reward.” Like mistaking busyness for productivity. To get out of that particular busyness tunnel, Violante suggests experimenting with checking mail on a schedule.

That idea, which Violante herself has adopted, is based on research that found smokers given a smoking schedule had greater success quitting than through other methods. The reason, researchers surmised, is that a schedule not only gave people practice and confidence in not smoking, but also broke the link between habitual smoking cues and actually lighting up. A similar idea holds true for email: a 2015 study found that people who check their email on a schedule felt happier and less stressed out than those who checked constantly – which many of us do, spending about five hours a day nosing about our inboxes.

Violante also suggests that teams set communication protocols for when a response is expected and agree to send emails out only during work hours. To preserve mental bandwidth, she recommends an email mindset shift. “It’s not about having, literally, zero emails in your inbox, but having no ambiguity about what’s in there and having a plan for what’s most important to respond to,” she explains. Though she recognises it’s not easy. “Even behavioural scientists have addiction problems with email.”

How scarcity shrinks mental bandwidth

The concepts of scarcity and tunnelling were first described in behavioural science research on poverty. Anandi Mani, a professor of behavioural economics at the Blavatnik School of Government at Oxford, and her colleagues wanted to understand what led poor people to make bad choices with their money, such as borrowing at high interest rates or playing the lotto, that can keep them trapped in poverty.

They studied sugar cane farmers in India, and gave them cognitive tests both when the farmers were flush with money right after harvest and when, months later, money was scarce. The researchers found that scarcity itself created such a tax on mental bandwidth that the farmers’ IQ tests dropped 13 points between flush and scarce times.

A research study on sugar cane farmers found that time scarcity creates such a tax on mental bandwidth, it can even temporarily lower IQ (Credit: Getty Images)

“There is a direct parallel between scarcity of money and scarcity of time,” Mani says. “With money, we do what’s urgent – we pay this bill, we try to make the budget work, even when we know it’s more important to take time to be a good parent or talk to your mom. At work, it’s the same. We get captured by whatever’s in front of our face, and we don’t give ourselves the space or introspection to think about what might be more meaningful to do.”

To step out of the time scarcity tunnel, Mani suggests first becoming aware of how you may be trapped in busyness. If you can, you might try smoothing your workload or spreading it out over time, much like research on how income smoothing helps those with money scarcity better weather financial volatility and keep from falling into episodic poverty. Then work with others to create and enforce group norms around taking breaks – at work, during the week, at the weekend.

“The old rules – you don’t work on the Sabbath – creating forced slack in our schedules, has real value,” Mani says. She herself is experimenting with 15 minutes of meditation every morning. “It’s making me more aware during the day,” she says. “Honestly, this is a topic which pushes me to a lot of soul searching.”

Plan your time with greater care

Anuj Shah, a professor of behavioural science at the University of Chicago, says scarcity creates its own mindset. His research, in which participants played online games and were either “rich” or “poor” in the number of guesses or attempts allowed, was surprising. Those who were “poor” were actually much more accurate or careful with their resources. But because scarcity narrowed their bandwidth, they were so focused on the current round, they were unable to strategise about the future and made disastrous choices, like borrowing at exorbitant rates, that wound up costing them dearly.

We can avoid the scarcity trap if we treat our schedules like a spacious art gallery, rather than an overflowing pantry (Credit: Alamy)

So to keep from tunnelling on the wrong thing or neglecting important tasks that seem less urgent at the moment but will pay greater dividends in the long run, Shah says, people need to recognise that time and bandwidth are limited resources and begin to think of choices around them as trade-offs.

For instance, he says, when we look at our calendar six months from now, it often appears wide open and free of all commitments. So we can overcommit ourselves, which can lead to more time scarcity and tunnelling in the future. “But we know that in six months, that week is going to look a lot like this week, which is usually pretty busy,” Shah says. “So you need to think – how would I fit this in this week? What would I have to give up to do it? We need to realise that slack in the future is an illusion.” It’s a practice he follows as well.

Shah’s colleague Sendhil Mullainathan suggests thinking about our schedules as less like a pantry that we cram anything and everything into, and more like an art gallery where we intentionally decide what is most important and how to arrange it so that everything fits. He recommends setting alerts to help us remember what’s important when we start to fall into the scarcity trap.

“Once we’re short on time, we’re already in a bad situation,” Shah says. “But if we learn to manage the time beforehand, we can keep that from happening in the future.”

Brigid Schulte is a journalist, author of Overwhelmed: Work, Love and Play when No One has the Time, and director of the Better Life Lab at New America