Every morning, Mrs. Chen dons her bright purple tai chi pajamas and joins the dozen or so other members of Hongmen Martial Arts Group for practice outside Chongqing’s Jiangnan Stadium. But a few months ago, she was in such a rush to join their whirling sword-dance routine that she dropped her purse. Fortunately, a security guard noticed it lying in the public square via one of the overhead security cameras. He placed it at the lost and found, where Mrs. Chen gratefully retrieved it later.

“Were it not for these cameras, someone might have stolen it,” Mrs. Chen, who asked to be identified by only her surname, tells TIME on a smoggy morning in China’s sprawling central megacity. “Having these cameras everywhere makes me feel safe.”

What sounds like a lucky escape is almost to be expected in Chongqing, which has the dubious distinction of being the world’s most surveilled city. The seething mass of 15.35 million people straddling the confluence of the Yangtze and Jialing rivers boasted 2.58 million surveillance cameras in 2019, according to an analysis published in August by the tech-research website Comparitech. That’s a frankly Orwellian ratio of one CCTV camera for every 5.9 citizens—or 30 times their prevalence in Washington, D.C.

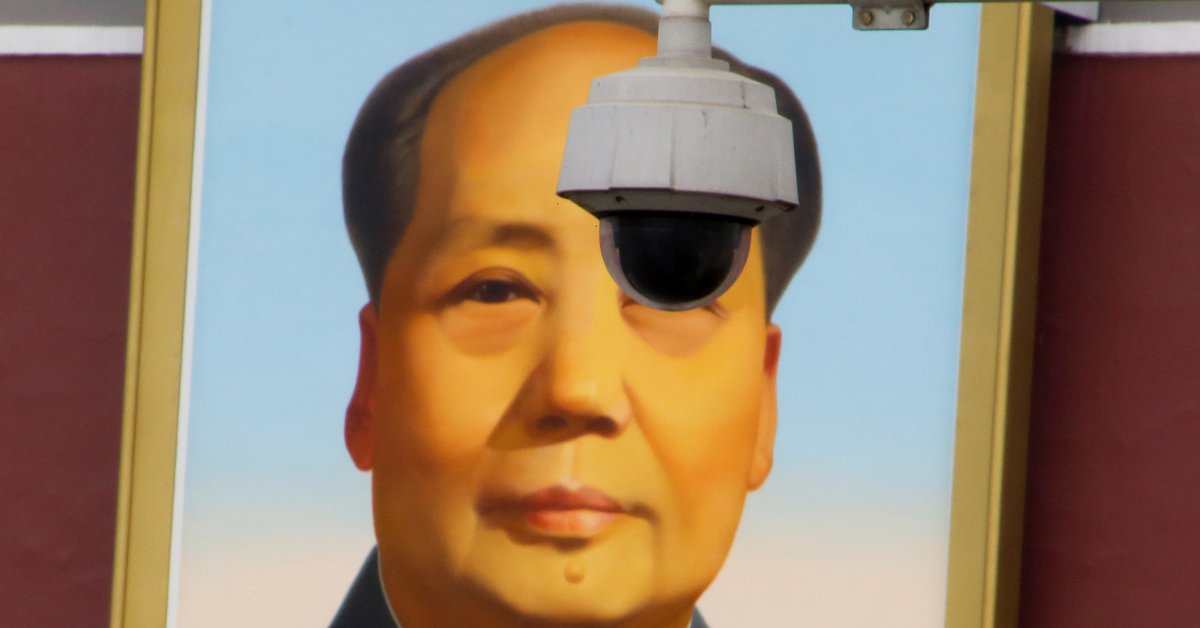

Every move in the city is seemingly captured digitally. Cameras perch over sidewalks, hover across busy intersections and swivel above shopping districts. But Chongqing is by no means unique. Eight of the top 10 most surveilled cities in the world are in China, according to Comparitech, as the world’s No. 2 economy rolls out an unparalleled system of social control. Facial–recognition software is used to access office buildings, snare criminals and even shame jaywalkers at busy intersections. China today is a harbinger of what society looks like when surveillance proliferates unchecked.

A protester covers a camera outside a government office in Hong Kong in July Chris McGrath—Getty Images

But while few nations have embraced surveillance the way China has, it is far from alone. Surveillance has become an everyday part of life in most developed societies, aided by an explosion in AI–powered facial–recognition technology. Last year, London police made their first arrest based on facial recognition by cross–referencing photos of pedestrians in tourist hot spots with a database of known felons. A few months earlier, a trial of facial–recognition software by police in New Delhi reportedly recognized 3,000 missing children in just four days. In August, a wanted drug trafficker was captured in Brazil after facial-recognition software spotted him at a subway station. The technology is widespread in the U.S. too. It has aided in the arrest of alleged credit-card swindlers in Colorado and a suspected rapist in Pennsylvania.

Still, the risks are considerable. As Western democracies enact safeguards to protect citizens from the rampant harvesting of data by government and corporations, China is exporting its AI-powered surveillance technology to authoritarian governments around the world. Chinese firms are providing high-tech surveillance tools to at least 18 nations from Venezuela to Zimbabwe, according to a 2018 report by Freedom House. China is a battleground where the modern surveillance state has reached a nadir, prompting censure from governments and institutions around the globe, but it is also where rebellion against its overreach is being most ferociously fought.

“Today’s economic business models all encourage people to share data,” says Lokman Tsui, a privacy expert at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. In China, he adds, we are seeing “what happens when the state goes after that data to exploit and weaponize it.”

Some 1,500 miles northwest of where Mrs. Chen recovered her purse, surveillance in China’s restive region of Xinjiang has helped put an estimated 1 million people into “re-education centers” akin to concentration camps, according to the U.N. Many were arrested, tried and convicted by computer algorithm based on data harvested by the cameras that stud every 20 steps in some parts.

In the name of fighting terrorism, members of predominantly Muslim ethnic groups—mostly Uighurs but also Kazakhs, Uzbeks and Kyrgyz—are forced to surrender biometric data like photos, fingerprints, DNA, blood and voice samples. Police are armed with a smartphone app that then automatically flags certain behaviors, according to reverse engineering by the advocacy group Human Rights Watch. Those who grow a beard, leave their house via a back door or visit the mosque often are red-flagged by the system and interrogated.

Sarsenbek Akaruli, 45, a veterinarian and trader from the Xinjiang city of Ili, was arrested on Nov. 2, 2017, and remains in a detention camp after police found the banned messaging app WhatsApp on his cell phone, according to his wife Gulnur Kosdaulet. A citizen of neighboring Kazakhstan, she has traveled to Xinjiang four times to search for him but found even friends in the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP) reluctant to help. “Nobody wanted to risk being recorded on security cameras talking to me in case they ended up in the camps themselves,” she tells TIME.

Surveillance governs all aspects of camp life. Bakitali Nur, 47, a fruit and vegetable exporter in the Xinjiang town of Khorgos, was arrested after authorities became suspicious of his frequent business trips abroad. The father of three says he spent a year in a single room with seven other inmates, all clad in blue jumpsuits, forced to sit still on plastic stools for 17 hours straight as four HikVision cameras recorded every move. “Anyone caught talking or moving was forced into stress positions for hours at a time,” he says.

Bakitali was released only after he developed a chronic illness. But his surveillance hell continued over five months of virtual house arrest, which is common for former detainees. He was forbidden from traveling outside his village without permission, and a CCTV camera was installed opposite his home. Every time he approached the front door, a policeman would call to ask where he was going. He had to report to the local government office every day to undergo “political education” and write a self-criticism detailing his previous day’s activities. Unable to travel for work, former detainees like Bakitali are often obliged to toil at government factories for wages as miserly as 35¢ per day, according to former workers interviewed by TIME. “The entire system is designed to suppress us,” Bakitali says in Almaty, Kazakhstan, where he escaped in May.

The result is dystopian. When every aspect of life is under constant scrutiny, it’s not just “bad” behavior that must be avoided. Muslims in Xinjiang are under constant pressure to act in a manner that the CCP would approve. While posting controversial material online is clearly reckless, not using social media at all could also be considered suspicious, so Muslims share glowing news about the country and party as a means of defense. Homes and businesses now feel obliged to display a photograph of China’s President Xi Jinping in a manner redolent of North Koreans’ public displays for founder Kim Il Sung. Asked why he had a picture of Xi in his taxi, one Uighur driver replied nervously, “It’s the law.”

Besides the surveillance cameras, people are required to register their ID numbers for activities as mundane as renting a karaoke booth. Muslims are forced from buses to have their IDs checked while ethnic Han Chinese passengers wait in their seats. At intersections, drivers are ushered from their vehicles by armed police and through Tera-Snap “revolving body detector” equipment. In the southern Xinjiang oasis town of Hotan, a facial–recognition booth is even installed at the local produce market. When a system struggled to compute the face of this Western TIME reporter, the impatient Han women queuing behind berated the operator, “Hurry up, he’s not a Uighur, let him through.”

China strenuously denies human-rights abuses in Xinjiang, justifying its surveillance leviathan as battling the “three evils” of “separatism, terrorism and extremism.” But the situation has been described as a “horrific campaign of repression” by the U.S. and condemned by the U.N. Washington has also started sanctioning companies like HikVision whose facial–recognition technology is ubiquitous across the Alaska-size region. But Western aversion to surveillance is much broader and stems in no small part from abuses like the Facebook/Cambridge Analytica scandal, in which the “scraped” personal information of up to 87 million people was acquired by the political consultancy to swing elections around the world.

China is also rolling out Big Data and surveillance to inculcate “positive” behavior in its citizens via a Social Credit system. In China’s eastern coastal city of Rongcheng, home to 670,000 people, every person is automatically given 1,000 points. Fighting with neighbors will cost you 5 points; fail to clean up after your dog and you lose 10. Donating blood gains 5. Fall below a certain threshold and it’s impossible to get a loan or book high-speed train tickets. Some Chinese see the benefit. High school teacher Zhu Junfang, 42, enjoys perks such as discounted heating bills and improved health care after a series of good works. “Because of the Social Credit system, vehicles politely let pedestrians cross the street, and during a recent blizzard people volunteered to clear the snow to earn extra points,” she says.

Such intrusive government is anathema to most in the West, where aversion to surveillance is much broader and more visceral. Whether it’s our Internet browser history, selfies uploaded to social media, data scavenged from fitness trackers or smart-home devices possibly recording the most intimate bedroom conversations, we are all living in what’s been dubbed a “surveillance economy.” In her book The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, Shoshana Zuboff describes this as “human experience [broken down into data] as free raw material for commercial practices of extraction, prediction, and sales.”

When it comes to facial recognition, resistance is intense given the huge potential for indiscriminate data harvesting. The E.U. is reviewing regulations to give its citizens explicit rights over use of their facial-recognition data. While tech giants Microsoft and Amazon have already deployed the technology, they are also calling for clear legal parameters to govern its use. Other than privacy, there are equality issues too. According to a study by MIT Media Lab, facial-recognition software correctly identified white men 99% to 100% of the time, but that dipped as low as 65% for women of color. Civil-liberties groups are especially uneasy since facial recognition, despite its widespread use by American police, is rarely cited as evidence in subsequent court filings. In May, San Francisco became the first major U.S. city to block police from using facial–recognition software.

Even in China, where civil liberties have long been sacrificed for what the CCP deems the greater good, privacy concerns are bubbling up. On Oct. 28, a professor in eastern China sued Hangzhou Safari Park for “violating consumer privacy law by compulsorily collecting visitors’ individual characteristics,” after the park announced its intention to adopt facial–recognition entry gates. In Chongqing, a move to install surveillance cameras in 15,000 licensed taxicabs has met a backlash from drivers. “Now I can’t cuddle my girlfriend off duty or curse my bosses,” one driver grumbles to TIME.

Russia’s election meddling around the world highlights the risks of commercially harvested data being repurposed for nefarious goals. It’s a message taken to heart in Hong Kong, where millions have protested over the past five months to push for more democracy. These demonstrators have found themselves in the crosshairs after being identified via CCTV cameras or social media. Employees for state airline Cathay Pacific have been fired and others investigated based on evidence reportedly gleaned via online posts and private messaging apps.

This has led demonstrators to adopt intricate tactics to evade Big Brother’s all-seeing eye. Clad in helmets, face masks and reflective goggles, they prepare for confrontations with the police with military precision. A vanguard clutch umbrellas aloft to shield their activities from prying eyes, before a second wave advances to attack overhead cameras with tape, spray paint and buzz saws. From behind, a covering fire of laser pointers attempts to disrupt the recordings of security officers’ body-mounted cameras.

Fending off the cameras is just one response. When Matthew, 22, who used only his first name for his own safety, heads to the front lines, he always leaves his regular cell phone at home and takes a burner. Aside from swapping SIM cards, he rarely reuses handsets multiple times since each has a unique International Mobile Equipment Identity digital serial number that he says police can trace. He also switches among different VPNs—software to mask a user’s location—and pays for protest–related purchases with cash or untraceable top-up credit cards. Voice calls are made only as a last resort, he says. “Once I had no choice but to make a call, but I threw away my SIM immediately afterward.”

The Hong Kong government denies its smart cameras and lampposts use facial-recognition technology. But “it really comes down to whether you trust institutions,” says privacy expert Tsui. For Matthew, the risks are real and stark: “We are fighting to stop Hong Kong becoming another Xinjiang.”

Ultimately, even protesters’ forensic safeguards may not be enough as technology advances. In his Beijing headquarters, Huang Yongzhen, CEO of AI firm Watrix, shows off his latest gait-recognition software, which can identify people from 50 meters away by analyzing thousands of metrics about their walk—even with faces covered or backs to the camera. It’s already been rolled out by security services across China, he says, though he’s ambivalent about privacy concerns. “From our perspective, we just provide the technology,” he says. “As for how it’s used, like all high tech, it may be a double-edged sword.”

Little wonder a backlash against AI-powered surveillance is gathering pace. In the U.S., legislation was introduced in Congress in July that would prohibit the use of facial recognition in public housing. Japanese scientists have produced special glasses designed to fool the technology. Public campaigns have railed against commercial uses—from Ticket-master using facial recognition for concert tickets to JetBlue for boarding passes. In May, Democratic Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio–Cortez linked the technology to “a global rise in authoritarianism and fascism.”

Back in Chongqing, shopkeeper Li Hongmei sees only the positives. She says the public CCTV cameras right outside her convenience store didn’t stop a spate of thefts, so she had six cameras installed inside the shop. Within days, she says, she nabbed the serial thief who’d been pilfering milk from her shelves. “Chinese people don’t care about privacy. We want security,” she says. “It’s still not enough cameras. We need more.”

Write to Charlie Campbell at charlie.campbell@time.com.