In 3Q 2014 Google had $16.5 billion in revenue and $2.8 billion in profit. I proceeded to write an article entitled Peak Google. Fast forward to last quarter, and Google had $36 billion in revenue and $6.7 billion in profit, increases of 118% and 139% respectively. It is difficult to imagine being more wrong!

For the record, my thesis was not that Google’s revenue and profit growth were over; rather, like Microsoft in the 2000s, Google would continue to grow but that its relevance had peaked, in large part because brand marketing would become much more important on the web.

Frankly, this explanation makes things worse in a way: it is certainly true that some types of advertising have, as I predicted, worked much better on platforms like Facebook or Instagram (and it’s also true that Facebook gave up on competing for advertising on 3rd-party sites); it is also worth noting that much of that advertising is less traditional brand advertising, meant to increase brand affinity for future conversions, than it is demand-generating direct advertising (as opposed to Google’s demand-capturing direct advertising in Search). What truly misses the mark, though, is the suggestion that Google’s relevance has in any way decreased.

Five Years of Growth

I have owned up to getting the Peak Google article wrong in the Daily Update, particularly this post in 2017, but in the interest of accountability — and, naturally, this article — a quick review is in order.

First, I should have been clear from the get-go that the analysis did not apply to YouTube. Not only is YouTube a natural fit for brand advertising, which is traditionally video-based, it was also barely monetized at that point; clearly significant growth was coming from that property alone.1

Second, despite the fact I spent most of the early years of Stratechery writing about mobile and the extent to which its impact was underrated, particularly by those in the United States who had already adopted personal computers, I underrated mobile’s impact! First, mobile dramatically increased the number of users Google served in both developed and developing countries. Second, mobile dramatically increased usage from existing users, as the Internet was now in people’s pockets or purses, not only their desks or backpacks. Google’s market was in the process of getting much larger.

The biggest mistake, though, was in underestimating just how far Google could go in terms of showing users more ads, even once you accounted for more users using Google more often.

MOAR Ads

The first and most obvious way that Google showed users more ads was by literally inserting more ads into mobile search results. This was a development I tracked closely, wondering just how far the company would go as it added first a third ad, and then a fourth. I wrote in that Daily Update:

Admittedly, this observation has been largely critical: is Google’s revenue growth due to actual increased engagement or simply due to stuffing the screen with ever more ads? In fact, the appropriate answer is “Who cares?” I suspect my disproving attitude stemmed from Peak Google: the company continued to defy my general narrative, so surely the cause must be something untoward like a modern paid inclusion model. And, well, that’s kind-of-sort-of what it is…

That certainly may be vaguely distasteful — it was much more edifying for Google to argue, as they did a decade ago, that folks simply using the Internet meant they made more money — but that doesn’t mean it isn’t effective, and frankly, I haven’t given it enough credit.

Just as important, though, is the way in which Google responded to the threat posed by vertical search alternatives. Back when I wrote Peak Google, there was a lot of talk that mobile was a problem for Google because the new app paradigm would make it more likely that end users would go around Google. They would use Yelp for local search, Amazon for shopping, or Expedia for travel; sure, URLs and bookmark managers may have been too confusing for most users, but the “App Revolution” meant a vertical search engine was only a tap away.

In fact, though, this threat ended up being overstated for several reasons.

First, it turned out that users didn’t want to juggle multiple apps any more than they wanted to juggle multiple URLs. Search in the built-in browser was still the easiest and most obvious place to start.

Second, Google was willing to pay whatever was necessary to ensure it was the default search engine for those built-in browsers, including billions of dollars on an ongoing basis to Apple.

Third, Google started to transform mobile results in particular to be much more useful: instead of forcing users to click a link for an answer — something mobile users dislike about as much as downloading new apps — Google would give it to them; they didn’t even need to “feel lucky”. Most importantly, though, when it came to vertical search categories, Google would offer an entirely new kind of results page.

Expedia and TripAdvisor

This reason to discuss this topic now is because of disappointing earnings results from Expedia and TripAdvisor. From CNBC:

Shares of Expedia and TripAdvisor both reached new year-to-date lows during midday trading on Thursday, tumbling as much as 25%. The stock plunge comes after both the travel service stocks reported third-quarter earnings misses after the bell Wednesday. Both companies pointed to weakened visibility in Google search results as a long-term revenue headwind.

Expedia CEO Mark Okerstrom said on Expedia’s earnings call:

What we saw was a continued shift of essentially the free links further down the page, by other modules that were inserted and ultimately a shift of traffic from the SEO channel over to some of the other products whether it’s flight metasearch or hotel metasearch over time. Now of course as related to the hotel product, the lodging product, we are able to pick up some of that volume and that ultimately resulted in spending more on sales and marketing than we had otherwise would have. We are happy with the returns that we saw on it, but ultimately, not as good returns as we would see from the SEO channel.

TripAdvisor CEO Steve Kaufer said on TripAdvisor’s earnings call:

We did see some incremental SEO headwinds over the course of the quarter. It’s always hard to know exactly what Google is doing. We think of it as how far down the page are we is our organic result. And I think you’re seeing this across the industry as Google has gotten more aggressive. We’ve been predicting this of course for the past many years. We talked about it on our last call. We know that this SEO piece is an ongoing trend and we’re not predicting that it’s going to turn around.

Expedia and TripAdvisor used to be the same company; they play in closely related spaces. Expedia is an “OTA” — Online Travel Agent — where you can book hotels, plane tickets, etc.; TripAdvisor is focused on reviews but monetizes as a meta-search engine, i.e. by referring users to OTAs (although TripAdvisor, with its “instant booking” product, is not far from being an OTA itself).

OTAs and Aggregation Theory

OTAs have always been a special case when it comes to Aggregation Theory; like Aggregators, they serve customers on a zero marginal cost basis, and they have power over supply (hotels, primarily) by virtue of delivering them demand. The hangup for me is how they acquire that demand: first and foremost from Google.

Expedia’s Google play is straightforward: deliver highly-ranked answers to common queries like “Tickets to Tokyo” or “Hotels in Sydney”, and also become very good at buying search ads. TripAdvisor, meanwhile, leverages its reviews to rank highly on a whole host of terms related to traveling, and then offers booking functionality alongside those reviews.

What is notable in both cases, though, is that it is Google that ultimately owns the customer relationship, which is why I have always hesitated to call OTAs Aggregators:

This arrangement between OTAs and Google has long been beneficial to both sides. Google drives traffic to the OTAs, which can monetize that traffic via commissions extracted from suppliers.2 Google, meanwhile, not only receives relevant results it could serve to customers, but also makes billions of dollars from OTAs buying search ads.

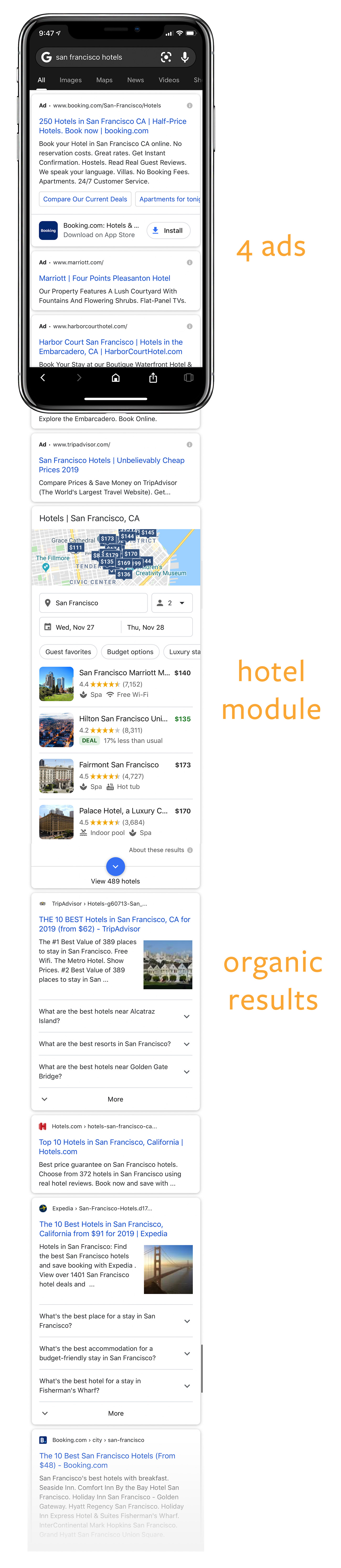

What has changed, starting with Google’s search results, which then spilled over to these companies’ financial results, is the hotel module:

First, note just how many screens you now have to scroll to reach organic results — at least 3 on an iPhone 11 Pro which is 812 points tall.3 Again, this isn’t necessarily new — Google has been adding ads for a while — but what makes the hotel module compelling is that, while it is easy to ignore the ads, the module is genuinely useful! You have a map of the city with prices of various hotels, an opportunity to specify your dates, and several options to click through on.

Here is the rub, though, at least from an OTA perspective:

In case you’re not sure what “Google Partners” means, here is a screen you get when you click on one of those hotels and look at the prices:

Everything in the hotel module is an ad, or perhaps more accurately, paid-inclusion. This particular example does not have Expedia.com (but it does have Hotels.com, which Expedia owns) or TripAdvisor, but they are in others; it is this module that Okerstrom was referring to when he said:

Now of course as related to the hotel product, the lodging product, we are able to pick up some of that volume and that ultimately resulted in spending more on sales and marketing than we had otherwise would have. We are happy with the returns that we saw on it, but ultimately, not as good returns as we would see from the SEO channel.

I would think not; the SEO channel is free, the hotel module isn’t.

Aggregating OTAs

At this point the conclusion seems easy, no? Google being evil, yet again. In fact, while I understand the frustration of Expedia and TripAdvisor, I think it is a bit more complicated.

Start with the theoretical perspective: the stable structure of an Aggregator-dominated market is that the Aggregator controls demand and suppliers come onto the Aggregator on the Aggregator’s terms. In other words, there are three players in the value chain: suppliers—Aggregator—demand. Notably, though, that has not been the case in travel, where Google has controlled demand but OTAs have controlled supply.

One way to achieve equilibrium would be for Google to become the one OTA to rule them all. Indeed, this would be difficult to compete with (and was a fear when Google acquired ITA in 2010). The truth, though, is that OTAs have put in significant effort to bring suppliers on board, and they deal with all of the pesky payment and customer support issues that Google loves to eschew. Instead Google has realized it can get OTAs to effectively pay Google to take care of the messy parts for them.

With the hotel module, Google captures demand more efficiently, which not only makes Google search more attractive to end users, but also transforms OTAs into suppliers, paying to provide the service that Google doesn’t want to. It is a textbook example of what Tren Griffin calls Wholesale Transfer Pricing:

Wholesale transfer pricing = the bargaining power of company A that supplies a unique product XYZ to Company B which may enable company A to take the profits of company B by increasing the wholesale price of XYZ.

In this case the unique product is demand — users. And this is where I am tempted to defend Google: at the end of the day, the company has the dominant position in its value chain largely by providing a better product. Search was better to start, but Google didn’t rest on its laurels: it made search better on mobile in particular with these sorts of modules, and while users could download another app or go to a different URL, they simply don’t want to.

At the same time, I get the frustration of the OTAs specifically and all of Google’s suppliers generally: if not even four ads will deter users, and if Google is going to pay whatever it takes to be the default search engine, then isn’t it unfair for the company to collect rent in this way?

Competing With Google

Here it is worth at least considering the biggest OTA of all, Booking Holdings. The company reported its earnings a day after Expedia; from Morningstar:

Booking Holdings Inc. reported third-quarter results that beat expectations. Profit at the online travel site was $1.95 billion, or $45.54 a share, up from $1.77 billion, or $37.02 a share, a year earlier. Adjusted earnings were $45.36, up 20% from a year earlier. Analysts polled by FactSet were expecting $44.50 a share. Revenue was $5 billion, up from $4.8 billion a year earlier. Analysts were expecting $4.85 billion.

Booking Holdings CEO Glenn Fogel argued on the company’s earnings call that the company was relatively insulated from Google’s actions:

Regarding SEO, we saw some headwinds in the SEO channel that did create some modest pressure, but it’s a small channel for us.

Fogel added later on:

In the end, what’s most important for us to get customers to come to us directly. We’ve talked about this a lot in the past. It’s one of the things that I think is very important. For us to have our own future is to create a service that is so wonderful, so good that people just naturally will come back to us directly. And we will not be as dependent on other sources of traffic.

This seems like unequivocally a good thing, no? Booking knows it can’t depend on the Google channel, that its future is best secured by innovating and building a customer experience that convinces users to go to Booking directly. That is competition working to the benefit of customers!

I had a similar thought while reading this profile of Yelp CEO Jeremy Stoppelman; the ‘hotel module’ was long ago preceded by the ‘local module’ on Google search, much to Yelp’s consternation. What always gave me pause about Yelp’s complaints, though, is that, as I noted earlier, the company was at one time held up as the canonical threat to Google on mobile; why didn’t the company earn more direct customers, and instead spend so much time and energy kvetching about Google’s search results? That is why I found this bit of that profile compelling:

It also surfaces reviews algorithmically via recommendation software. It segregates reviews that the software flags for being solicited or biased, or because it doesn’t know enough about a user. Which means Yelp hides almost 30% of the reviews posted to its site, according to the company. This review filter is, to put it mildly, enormously unpopular among businesses…

“I’m sure we could have been making a lot more money if we allowed ourselves to be compromised and just said: Anything goes on Yelp. You want 5 stars? Tell your friends to go write a bunch of reviews for you and they’ll be on Yelp and then you can advertise. And wouldn’t it be wonderful?” said Stoppelman.

Instead, Yelp went another route. It is vigilant about reviews, and has passed on some easy ways to make money from users’ data. It doesn’t let businesses target users who happen to be walking by with an ad, for example. Despite persistent rumors, it’s hard to imagine Yelp fitting in as an acquisition target for Big Tech — in just two interviews with BuzzFeed News, the outspoken Stoppelman took shots at Facebook, Amazon, and Google…

“When I look out at other companies,” Stoppelman said, “I see other priorities, namely growing revenue as much as possible. So why didn’t Facebook crack down on certain types of content, or why did they allow sensational stories or stories that are not true to blast across the network and get amplified so much? Had they had the foresight to say, ‘Hey, this is bad for the world’ or ‘This is bad for our long-term brand, we should shut it down,’ it probably wouldn’t have turned into an eventually traumatic political issue.

“But at the end of the day, collecting attention is the way that they make money, and they dial up the algorithm — the same as YouTube, same for Google. You know, it’s like Google and Facebook did the same thing: Use the algorithm to optimize for maximum attention. And if you optimize for maximum attention, you’re leaning into human nature of rubbernecking at train crashes, and all the worst stuff that humanity can provide. And that’s where you end up. And I’m sure it was like rocket fuel for their business, but now we’re paying the price.”

This is by far the most compelling pitch I have heard Yelp give for itself: “The big companies are full of spam and misinformation, while we take the time to get reviews right.” It is hard not to wonder just how much more popular Yelp’s product might be if this message were spread as stridently as its anti-Google arguments.

And, of course, there is Amazon: more product searches start on Amazon than Google, not because Amazon spent its energy complaining about Google favoring its own shopping results, but because Amazon went out and delivered a better experience for users.

Monopoly Concerns

I remain very concerned about monopoly, particularly, when it comes to consumer tech, digital advertising; this Wall Street Journal story is an excellent overview of how Google makes it extremely difficult to compete (for competitive ad-tech companies) and extremely difficult to go elsewhere (for its customers).

What gives me pause about search, on the other hand, is that there are not constraints on user movement. It really is trivial to use Yelp, or Amazon, or Booking, both on the web and on a smartphone. Is customer inertia something that requires regulation, or is it a possible spur to making products that are that much more compelling?

One answer, perhaps, lies in Google’s behavior itself: unlike traditional monopolies, it is hard to argue that Google’s product isn’t getting better. Sure, OTAs need to pay to play on the hotel module, but the hotel module is a genuine improvement over 10 blue links. The same can be said of the other areas where Google gives answers instead of options. I absolutely get the argument that this might be an unfair extension of Google’s search dominance, but the possibility of stifling innovation, both directly and also its incentives, are worth consideration.

I wrote a follow-up to this article in this Daily Update.

- It remains a big problem that we don’t know exactly what YouTube’s financials are; if Google won’t tell us the SEC should make them [↩]

- I’m using “Commissions” here broadly; there are multiple monetization models for OTAs, including selling rooms directly, charging hotels fees after-the-fact, etc. [↩]

- A “point” is the functional equivalent of a pixel in the user interface; an iPhone 11 Pro has a 3x retinal display which means that three physical pixels represent one “point” [↩]