Monitoring seismic activity all over the world is an important task, but one that requires equipment to be at the site it’s measuring — difficult in the middle of the ocean. But new research from Berkeley could turn existing undersea fiber optic cables into a network of seismographs, creating an unprecedented global view of the Earth’s tectonic movements.

Seismologists get almost all their data from instruments on land, which means most of our knowledge about seismic activity is limited to a third of the planet’s surface. We don’t even know where all the faults are since there’s been no exhaustive study or long-term monitoring of the ocean floor.

“There is a huge need for seafloor seismology,” explained lead study author Nathaniel Lindsey in a Berkeley news release. “Any instrumentation you get out into the ocean, even if it is only for the first 50 kilometers from shore, will be very useful.”

Of course, the reason we haven’t done so is because it’s very hard to place, maintain, and access the precision instruments required for long-term seismic work underwater. But what if there were instruments already out there just waiting for us to take advantage of them? That’s the idea Lindsey and his colleagues are pursuing with regard to undersea fiber optic cables.

These cables carry data over long distances, sometimes as part of the internet’s backbones, and sometimes as part of private networks. But one thing they all have in common is that they use light to do so — light that gets scattered and distorted if the cable shifts or changes orientation.

By carefully monitoring this “backscatter” phenomenon it can be seen exactly where the cable bends and to what extent — sometimes to within a few nanometers. That means that researchers can observe a cable to find out the source of seismic activity with an extraordinary level of precision.

The technique is called Distributed Acoustic Sensing, and it essentially treats the cable as if it were a series of thousands of individual motion sensors. The cable the team tested on is 20 kilometers worth of of Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute’s underwater data infrastructure — which divided up into some ten thousand segments that can detect the slightest movement of the surface to which they’re attached.

“This is really a study on the frontier of seismology, the first time anyone has used offshore fiber-optic cables for looking at these types of oceanographic signals or for imaging fault structures,” said Berkeley National Lab’s Jonathan Ajo-Franklin.

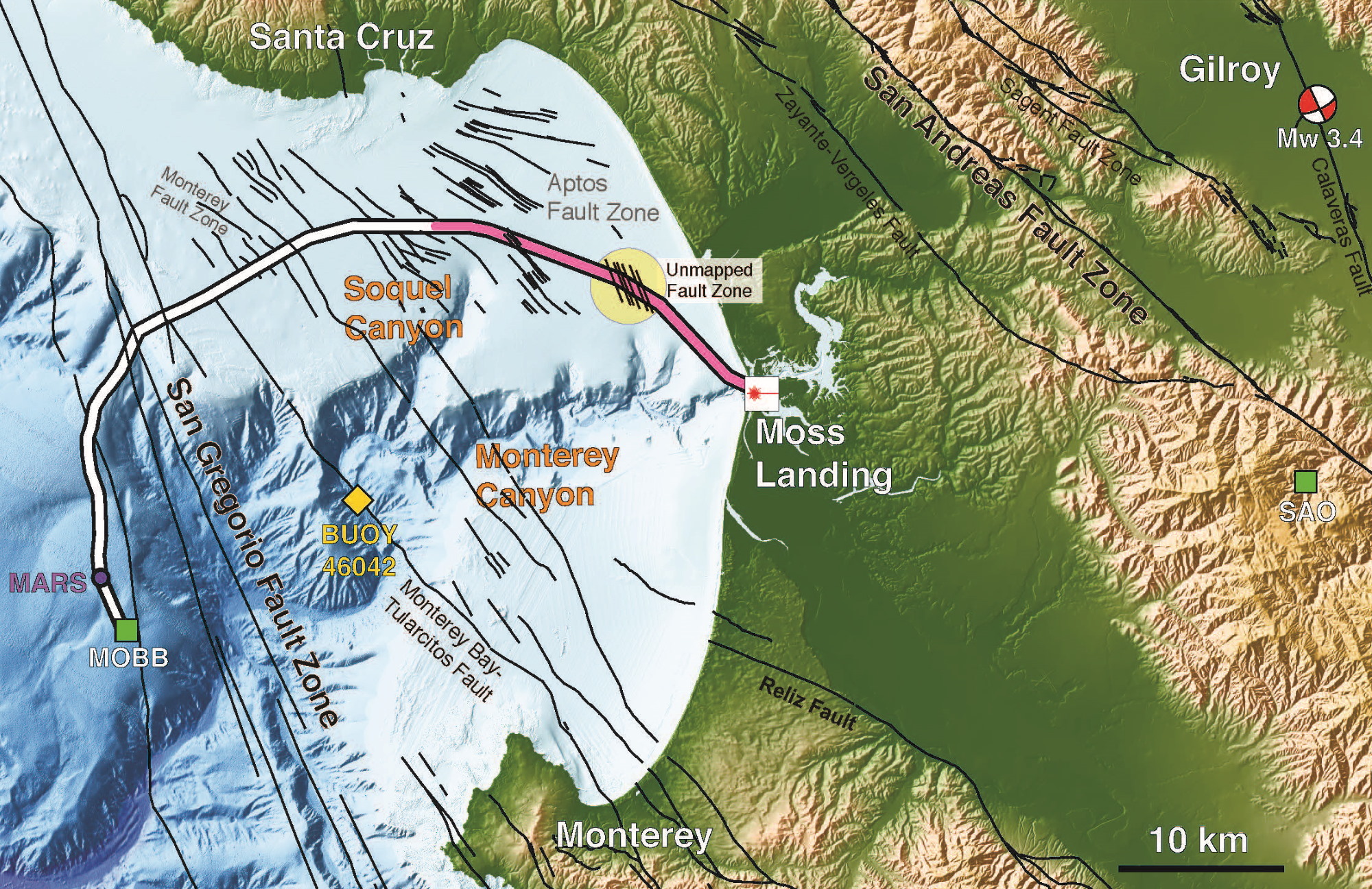

After hooking up MBARI’s cable to the DAS system, the team collected a ton of verifiable information: movement from a 3.4-magnitude quake miles inland, maps of known but unmapped faults in the bay, and water movement patterns that also hint at seismic activity.

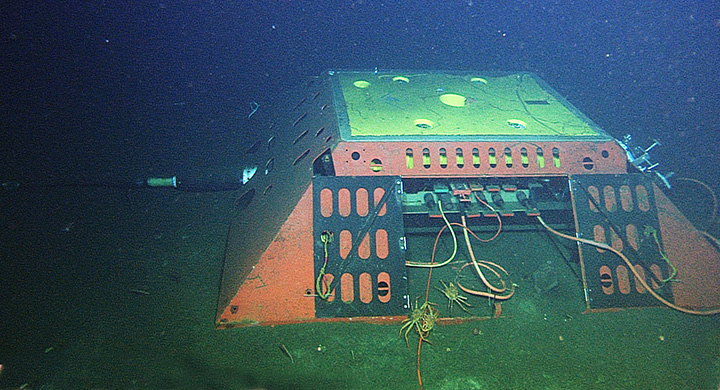

The main science node of the Monterey Accelerated Research System. Good luck keeping crabs out of there.

The best part, Lindsey said, is that you don’t even need to attach equipment or repeaters all along the length of the cable. “You just walk out to the site and connect the instrument to the end of the fiber,” he said.

Of course most major undersea cables don’t just have a big exposed end for random researchers to connect to. And the signals that the technology uses to measure backscatter could conceivably interfere with others, though of course there is work underway to test that and prevent it if possible.

If successful the larger active cables could be pressed into service as research instruments, and could help illuminate the blind spot that seismologists have as far as the activity and features of the ocean floor. The team’s work is published today in the journal Science.