The Yiwu-to-London train pulls into the DB Eurohub terminus in Barking, east London, 18 days after leaving the Chinese city, a trading centre south of Shanghai. Over the course of its 7,500-mile (12,000km) journey to Europe, the train has wound its way through Kazakhstan, Russia, Belarus, Poland, Germany, Belgium and France, following part of the old east-west Silk Road.

This freight-rail link is just one of many new routes that, along with roads and ports, form China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Whether the branding is an elaborate PR exercise or a new version of the Silk Road, what is real is that as China globalises, its investment is being gratefully sought across Europe. From ports to power stations, football clubs to financial companies, from the Norwegian city of Kirkenes to the Greek port of Piraeus and the Portuguese national grid, Chinese investment has become indispensable to the European economy. However, the country’s rise as a global economic power poses a strategic dilemma for European governments. The French president, Emmanuel Macron, warned in March that the “period of European naivety” about China had to end.

Is this overblown fear bordering on xenophobia? Workers at British Steel’s Scunthorpe plant will surely be grateful that the company has been sold to the Chinese Jingye Group, saving 4,000 jobs. EU state aid rules were blamed for preventing the nationalisation that steel unions demanded, but even the hardest of Brexits under World Trade Organization rules would have limited Britain’s ability to give state aid to an ailing company. That many Chinese investors have a financial link to the Chinese state or, in some cases, are fully state-owned is more than coincidental. It raises questions about the geopolitical motivation for much Chinese investment around Europe: why would a Chinese company see a failing British steelmaker as a good investment?

Over recent months, I and other journalists from around Europe have been looking in depth at the Chinese investment offensive, seeking to assess its scale and how welcome, or worrying, it is. Viktor Orbán’s Hungary is the only EU country with a significant Silk Road project – a €2bn high-speed Budapest-to-Belgrade railway (linked to Piraeus) financed with Chinese credit. A €357m bridge in Croatia is under construction by a Chinese company, four-fifths of it funded by EU taxpayers.

Overall Chinese investments in Europe have been increasing at a steady pace over the last two decades across most industries and sectors. From 2008 to 2018, China spent an estimated €300bn on the acquisition of European companies or the establishment of their subsidiaries in Europe (the EU plus Switzerland and Norway). Britain, Germany and France have attracted most of the Chinese investment in the last decade. To keep things in perspective, this is not as much as EU companies have invested in China, and is just a fraction of US investment in Europe.

However, in March the EU issued a paper declaring China a “systemic rival”. As this shift in language signalled, there’s a new level of concern in Brussels that the billions member governments are accepting from China will leave it strategically compromised. Signs of this backlash can be dated to at least December 2016, when the Chinese household appliance group Midea bought the German robotics manufacturer Kuka – regarded as a pearl of German industry – for €4.5bn. Michael Clauss, then German ambassador in Beijing, and currently Germany’s permanent representative to the EU, said it was “to be feared” that such companies as Kuka “will only be used as tools and thrown away once they have transferred sufficient technology”.

Yet, take the example of Chinese car manufacturer Geely. In 2010, for about $1.5bn the company acquired the loss-making Swedish manufacturer Volvo in a deal that turned out to be highly successful for both sides. Sweden’s car brand flourished and Geely benefited from the technological cooperation. In 2017, it added a majority stake in Lotus, the British sports car manufacturer, to its portfolio, followed by a 9.69% stake in the Mercedes-Benz owner Daimler. In 2013, Geely purchased London Taxis International, paying £11.4m for the manufacturer of the distinctive London black cab that had just gone into administration. Now rebranded as the London Electric Vehicle Company the investment revitalised the Coventry plant, making it the first in the UK dedicated solely to the production of electric vehicles. Such acquisitions have by no means been to the detriment of the companies affected, including Kuka. In most cases, managers and employees, from Norway to Italy, confirmed to us that the acquired companies are better off today than before they were sold.

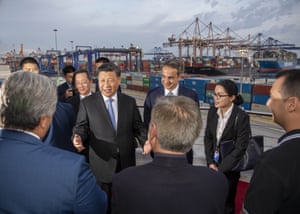

The caution being expressed now by some EU governments is also undermined by the reality that debt-burdened countries – Greece, for example – have had little alternative. China’s first major investment in Europe was in Piraeus (one of 13 European ports in which China has a foothold). But the privatisation of Greek infrastructure was imposed by international lenders as a condition of bailing out its economy. Likewise in Portugal, where investments in the electricity grid totalling more than €9bn – including by China’s state-owned companies State Grid and China Three Gorges – now make Portugal a “strategic partner”, according to China’s ambassador to Lisbon. “We were forced to privatise by the market logic, and eventually sold to state capitalist companies,” said Raquel Vaz-Pinto, a political scientist at the University of Lisbon.

That the EU now frets about the extent of China’s investment in critical infrastructure but fails to acknowledge that its own policies partly created the vulnerability is evidence of a divided and profoundly inconsistent approach to China.

Post-Brexit, could the UK find itself in a similar bind to that of Greece and Portugal: desperate for a trade deal but with weakened negotiating power? And what of the risk of China leveraging its economic might to silence criticism of its human rights violations? Dependence on Chinese funding clearly promotes self-censorship. Chinese students make up about a quarter of the total number of foreign students in the UK and concern about this was debated recently in the House of Commons. Academics partnering with Chinese educational institutions risk the loss of their Chinese visas if they speak out. It is why the Dalai Lama, who was before 2016 was given the red-carpet treatment by most governments has not been received by any major European politician since 2016. One only has to look at the treatment of the Uighurs in Xinjiang to see how the Chinese state deals with any challenges to its authority. British Steel workers would be justified in looking with alarm at the violence in Hong Kong and how UK criticisms are received in Beijing.

A sign of the EU’s new assertiveness is its screening tool for foreign direct investment, the first real joint effort to scrutinise China’s takeovers. Macron’s comments also show that the contradictions in the EU’s position are belatedly being recognised. But the on-again-off-again US-China trade war should be a warning that, without a coherent European approach, governments seeking trade and business deals from both sides could increasingly find that they are the collateral damage.

• Juliet Ferguson is a journalist at Investigate Europe, a media co-operative drawn from eight European countries