Put a big red circle on your calendar for Thursday night (Nov. 21), for skywatchers will be out in force, anxiously waiting for and hoping to get a view of a meteor shower that almost nobody has heard of.

But the Alpha Monocerotids are this autumn's skywatching wild card.

Annual meteor displays such as the August Perseids and the December Geminids usually produce rates of 60 to 120 meteors per hour and reliably put on a good show every year, whereas in most years the Alpha Monocerotids produce little or nothing. But on four occasions: 1925, 1935, 1985 and 1995, skywatchers have been surprised by a short-lived burst of meteors emanating from the direction of the obscure constellation of Monoceros, the Unicorn on the night of Nov. 21-22.

Only one or two observers caught the first three of these events. However, the 1995 shower was anticipated in advance and on the appointed night many came away seeing meteors briefly fall at rates of 5 or 6 per minute.

Related: Meteor Storms: How Supersized 'Shooting Star' Displays Work

Now, Peter Jenniskens, a senior research scientist with the SETI Institute and NASA's Ames Research Center along with Esko Lyytinen of the Finnish Fireball Network , have just announced in a short technical paper that circumstances appear excellent for a repeat performance this coming Thursday night, with a small chance that the shower could turn extraordinary.

So well-positioned meteor observers — especially those in the eastern U.S. and eastern Canada — are going on high alert.

Editor's note: If you capture an amazing photo or video of this potential meteor storm and would like to share it with Space.com and our partners for a story or image gallery, send images and comments in spacephotos@space.com.

Surprise!

The first known Alpha Monocerotid outburst came in 1925, when late on the night of Nov. 20, F.T. Bradley of Crozet, Virginia, caught sight of 37 meteors in just 13 minutes. He ran inside to get star charts for plotting the paths of the meteors and resumed his observations 10 minutes later, but didn't see another meteor. Without plotting any of the previously seen meteors, Bradley estimated that they emanated somewhere below the Orion constellation. Another witness was noted meteor expert Charles P. Olivier, who was working in the observatory at the University of Virginia. Stepping outside for only a few moments and scanning the sky, he caught sight of "three bright meteors" within just a minute.

Ten years later, in 1935, during the early hours of Nov. 22, professor Mohd. A.R. Khan from Begumpet, India, witnessed a "fine shower of meteors" emanating from the constellation of Monoceros, the Unicorn. In just 20 minutes he counted over 100 meteors, which quickly dwindled to 11 in the next 20 minutes. At the same time, the commanding officer of the USS Canopus, then anchored in Manila harbor, saw meteors at the rate of 2 per minute during a 30-minute interval.

After being dormant for half a century, the Alpha Monocerotids came to life again on the morning of Nov. 21, 1985, for two observers in California. Keith Baker, a night assistant at the Lick Observatory counted 18 meteors in just 7 minutes coming from a region near Canis Minor. And from Capitola, Richard Ducoty saw 27 meteors in 4 minutes, before this burst of activity rapidly trailed off to nine during the next 14 minutes. He commented that the brightest meteors ranged from 0 to negative 2 magnitude (as bright as Jupiter), also noting that their speed was quite fast, a little slower than the Leonids.

Assuming that the shower would rev up again in 1995, Jenniskens published an announcement in WGN, the Journal of the International Meteor Organization, alerting prospective observers of a possible outburst of Alpha Monocerotid meteors. Europe was in the favored viewing zone. Jenniskens and members of Dutch Meteor Society, chose the Calar Alto Astronomical Observatory located in Almería Province in Spain to watch for the expected meteor show.

In his book "Meteor Showers and Their Parent Comets" (Cambridge University Press, 2006), Jenniskens wrote:

"Suddenly, around 0:10 UT, three meteors radiated from a point on the border of the constellations Canis Major and Monoceros, 15° away from the position (radiant) given in past accounts. And this time it did not stop after just a few. Meteors started pouring out of Canis Minor, falling left and right, up and down. Bright meteors too. By 1:29 UT meteors were falling at a rate of five or more per minute. Twenty minutes later it was all over. Emotions were strong when the stream peaked that night on Calar Alto, and we broke down in tears."

Considering that over the past century, three of the four outbursts were unexpected and seen by so few people Alpha Monocerotid displays may have happened in other years without ever being noticed.

Encore in 2019?

The source of the Alpha Monocerotids is unknown, but the stream's orbital characteristics point to a comet with an orbital period of less than 600 years. Apparently, when this anonymous visitor last passed through the inner solar system it should have released a trail of fine rubble following along its path. Some of this comet dross from roughly half a millennium ago should only now be completing its first revolution around the sun, decades behind their parent comet. The trail of rubble is dense, but exceedingly narrow, with a half-width measuring only about 26,000 miles (42,000 kilometers). The meteoroids collide with Earth at a speed of 41 miles (66 km) per second; very similar to the October Orionids.

Both Jenniskens and Lyytinen have shown that the Alpha Monocerotid outbursts of 1925, 1935, 1985 and 1995 all arose when Earth passed through this one lengthy debris trail.

And now the stage is set again.

When and where

On Thursday night (Nov. 21) at about 11:50 p.m. EST (0450 GMT on Nov. 22), plus or minus 2 minutes, Jenniskens expects Earth to pass within 18,600 miles (30,000 km) of this one-revolution rubble trail with a margin of error equal to this predicted miss distance. In other words, anywhere from about 37,000 miles (60,000 km) to a direct hit. Correspondingly, meteor rates could run anywhere from 100 to "possibly" 1,000 per hour!

However, there are a few disclaimers that need to be stressed.

If you plan to look for meteors, try to get to a viewing site as far as possible from bright lights. Also, try to get to a place that will provide you with a wide-open view of the sky, free from obstructions like tall trees or buildings. In short: the darker your sky and the more sky you can see, the more meteors you'll see.

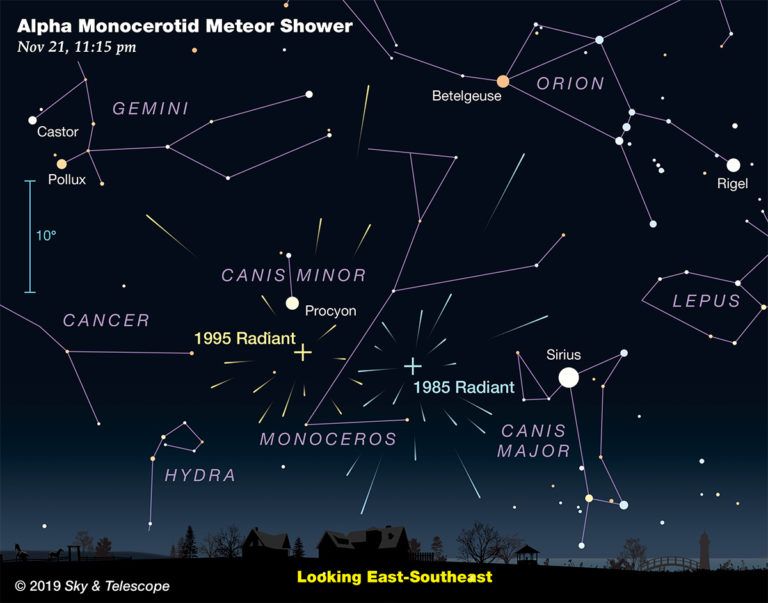

Unfortunately, because the location of the shower radiant — that region of the sky where the meteors will be darting from — is below and to the lower right of the bright yellow-white star Procyon in Canis Major, it will be only about one-quarter up above the east-southeast horizon for most of the eastern U.S. and eastern Canada.

Thanks to that low altitude, the number of meteors that may actually be seen will be considerably reduced by at least 50%. So, if the meteor outburst reaches 1,000 per hour, at least half of those meteors will be out of sight, streaking below the horizon. If the rate is 100 per hour, then a single observer might see 50 or less.

And the farther west you are located, the lower the radiant and the lower the total number of meteors you're likely to see. For those living in the Rocky Mountains and the desert Southwest, the radiant will be sitting on or near the horizon at the time of the expected peak (9:50 p.m. MST). So, any shower members seen will be "earthgrazers" that skim far across the top of the atmosphere nearly horizontally and leave long, colorful, persistent trains.

Unfortunately near and along the West Coast of both the U.S. and Canada, the radiant will be below the horizon, so the number of any visible meteors are likely to be few and far between at the peak (8:50 p.m. PST).

Don't be late!

Like previous outbursts, this upcoming display should be very short lived. Notes Lyytinen: "Anyone who is going to try to observe should not be late at all. The strongest maximum would fit in about 15 minutes, or maybe a little bit less. It will be almost completely over in about 40 minutes. I recommend starting the observations at the latest at 04h30m (11:30 p.m. Eastern Time) and if you don't want to miss any meteor, then start no later than at 4h15m (11:15 p.m. Eastern Time)."

Now all we can do is hope for clear skies.

- NASA Surprised by Unexpected Meteor Outburst

- Shooting Star Reflections: The Great Leonid Meteor Storm of 1966

- How Meteor Showers Work (Infographic)

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.