Australia exports about 1 billion metric tons of iron ore each year and 300 metric tons of gold. Yet, beyond these well-known commodities lies a suite of lesser-known minerals, which are critical for the world's advancement.

Critical minerals are designated critical for their essential role in modern technologies. They are identified as critical based on a number of factors including supply chain security, economic benefits and strategic importance.

Australia already packs a punch in global critical mineral supply, producing 14 of the 31 minerals listed in Australia's Critical Minerals List. However, as the world's reliance on technology increases, and countries transition to renewable energy, there is an opportunity for Australia to grow its stake further.

The hidden gems: Gallium and germanium

Among Australia's unsung critical minerals are gallium and germanium. Like many critical minerals, they are not typically mined directly but are by-products of the processing of other minerals.

Both minerals hold significant growth potential for Australia, despite the country's current limited production.

Despite gallium being as abundant on earth as copper, it never occurs at high enough concentrations to mine. It occurs in small but appreciable quantities in bauxite which is the main ore source of alumina.

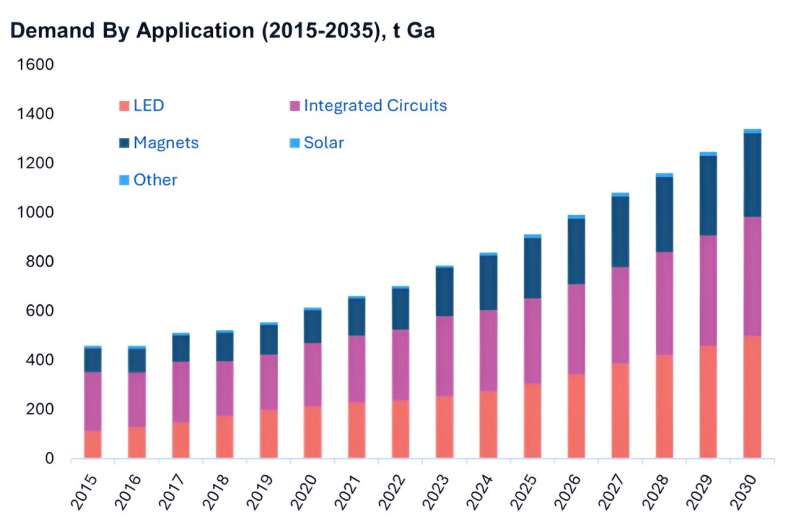

Global demand for gallium is only about 708 metric tons, so even small amounts are valuable.

Gallium is crucial for producing high-speed semiconductor chips and LEDs. It is also used to create solar photovoltaic (PV) cells and electronic devices that operate at high frequencies and temperatures, making it ideal for military and satellite communications.

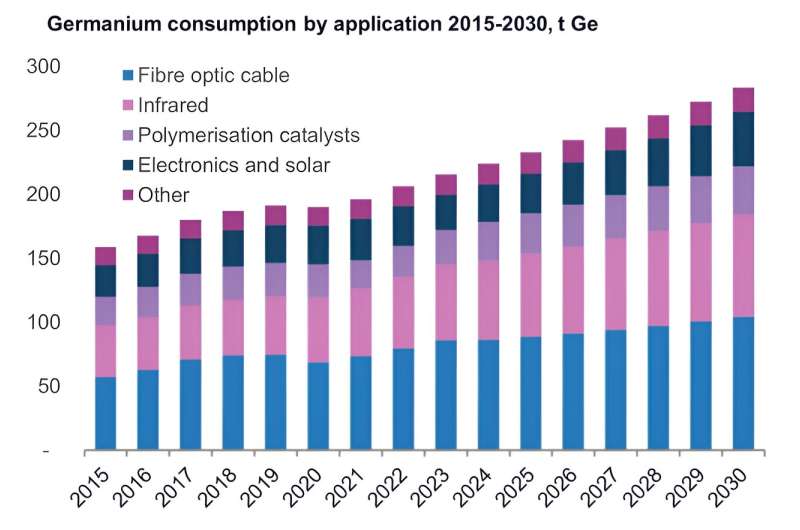

Germanium is a by-product of lead and zinc mining. This mineral plays a pivotal role in renewable technologies, particularly in solar cells and fiber optics, enhancing their efficiency and performance.

The global production of germanium is currently around 220 metric tons annually.

Unlocking Australia's critical mineral potential

Dr. Chris Vernon is our Australian Critical Minerals R&D Hub Lead. He said Australia had most of the critical minerals on any country's list so there was huge potential to grow.

"Gallium and germanium have recently gained attention because China is the main producer of each and the Chinese government has indicated that it will control export for strategic reasons. However, there are many other critical mineral markets Australia could have a role in," Chris said.

"Large amounts of potential byproduct is either left in the ground, goes to tailings, or is exported as a contaminant in the primary product because they don't usually cooperate, or separate easily, so you need process technology, and equipment.

"The cost of separating can be significant, and there's a lot of competition on price, so the decision to separate out some of these materials is often made on strategic grounds, rather than on economics."

The need for strategic mineral management

As part of the Australian Critical Minerals Research and Development Hub launched late last year, a project is underway with Geoscience Australia and ANSTO. It sets out to estimate the resource potential of critical minerals like gallium, germanium and indium in Australian zinc deposits.

The project aims to evaluate the techno-economic opportunities for Australia to produce these minerals from existing operations and explore the technical recovery of gallium from existing bauxite refineries.

Citation: Though small in volume, gallium and germanium hold big potential for the global critical minerals market (2024, June 20) retrieved 20 June 2024 from https://techxplore.com/news/2024-06-small-volume-gallium-germanium-big.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.